Panamanian archaeology

Pioneering Panama's past

A new generation stands on the shoulders of giant (archaeologists)

Archaeology Historical Ecology Anthropology Life in Deep Time Naos CTPA purple

Ashley Sharpe

purple

Ashley SharpePanamanian

archaeology

Pioneering Panama's past

A new generation stands on the shoulders of giant (archaeologists)

Archaeology Historical Ecology Anthropology Life in Deep Time Naos CTPA purple

Ashley Sharpe

purple

Ashley SharpePanamanian

archaeology

Urban tungara frogs are

sexier than forest frogs

How do animals adapt to urban environments? In the case of the Tungara frog, city males put on a more elaborate display than males in forested areas.

Panama City, Panama

Cover photo by Brian Gratwicke

purple

Rachel Page

purple

Rachel PageFrog Sex

in the City

Family Day on Barro Colorado Island, SNI Honors Cooke and Sanjur, SENACYT’s plans for Coiba lab, Condolences to Kursar and Jackson families

Family Day on Barro Colorado Island, SNI Honors Cooke and Sanjur, SENACYT’s plans for Coiba lab, Condolences to Kursar and Jackson families, art meets science, new Fulbright-National Geographic fellow speaks at Naos, scientists host university students , Congratulations to Daney Ramirez, Corotú cafeteria changes hand, New digital giving campaign, STRI participates in local events

purple

purpleSpecial

Events

The University of Panama Hosts Symposium to Celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Herbarium, an important component of one of the principal institutions of higher education in the country

This major achievement is the result of years of work by a coordinated team at the University and dedicated, long-term support from local and international institutions.

purple

Noris Salazar

purple

Noris Salazar

In STRI’s carbon offset

program, everyone wins

STRI took a gamble on a carbon offset program in partnership with an indigenous community in eastern Panama. Ten years later, it has successfully met offset goals, empowered women, built environmental stewardship capacity, created a long-term research platform and offered hope for a community’s threatened forest-based traditions.

Ipetí Emberá, Panama

Photos by: Sean Mattson

purple

purpleReducing our

carbon footprint

An Indo-Pacific damselfish takes

hold on the other side of the globe

Smithsonian marine biologist Ross Robertson suspects that the regal demoiselle hitched a ride to the Gulf of Mexico on an oil rig. Its outstanding success in its new habitat raises questions about its impact in the Gulf.

Naos Island Laboratories, Panama

Marine Biology Invasion Biology Molecular Genetics and Genomics Fisheries and Marine Conservation Evolutionary Biology Exploration Connections in nature: Plants, Animals, Microbes and Environments Sustaining a Biodiverse Planet Naos purple

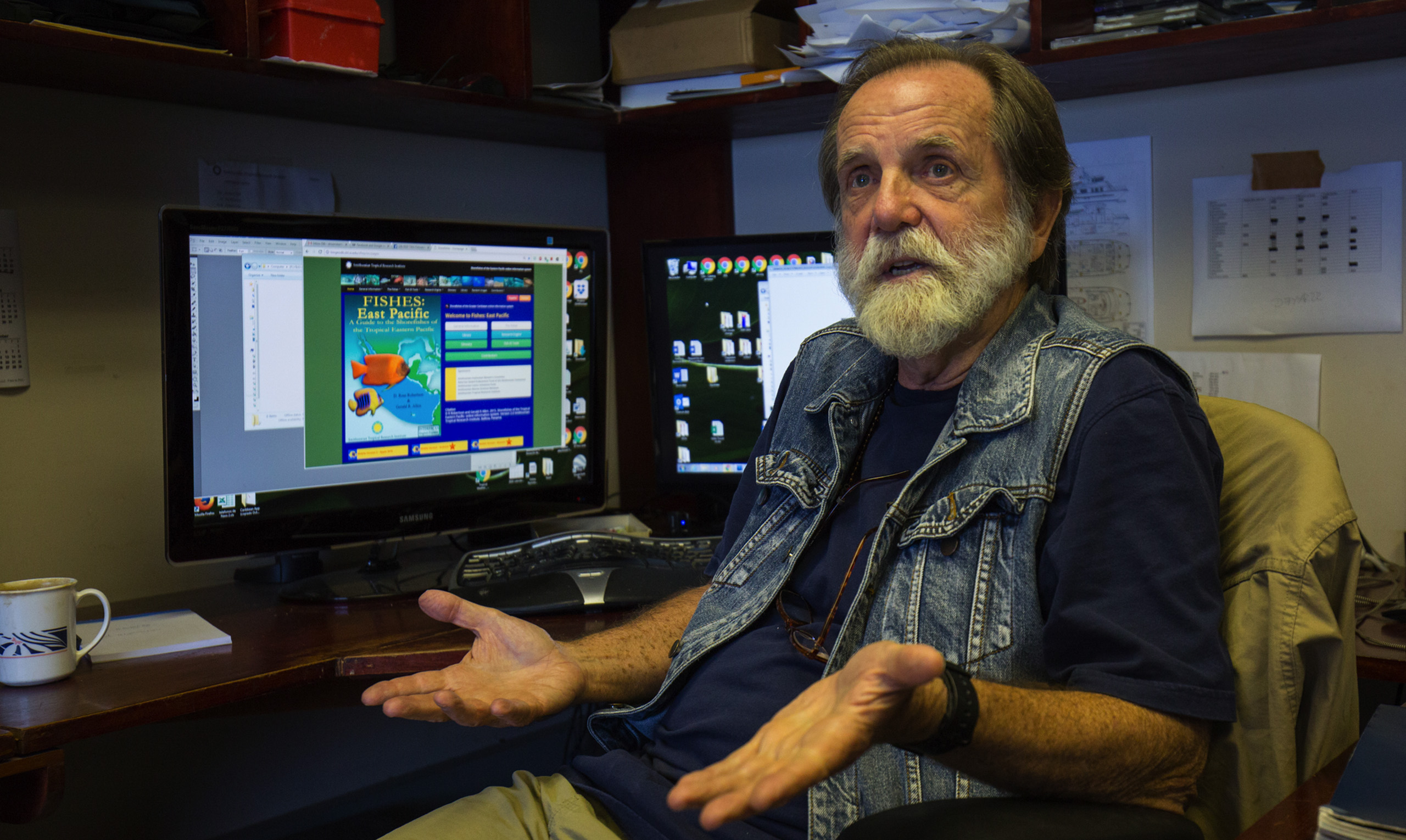

D. Ross Robertson

purple

D. Ross RobertsonA damselfish

moves to

Mexico

The rich marine fossil records of the tropics provide an opportunity to observe how complex life responds to natural and human-induced changes.

Research in my lab focuses on change in marine ecosystems over time, from millions of years ago to the recent past and the present day. Environmental and ecological transformation of the Caribbean caused by formation of the Isthmus of Panama and global climate changes over the last 10 million years provides a framework to unravel ecological and evolutionary processes in deep time. Human activity has also had a major impact on Caribbean life and this is revealed in young fossil records. By piecing together clues left by fossil coral, sponges, sharks, mollusks and fish, we reconstruct baseline conditions to help guide Caribbean reef conservation and improve our understanding of fundamental biological processes.

Modern Caribbean coral reefs are a pale shadow of what they once were, but exactly what did a “pristine” coral reef look like? Holocene fossil records of corals and mollusc skeletons, fish otoliths, sponge spicules and shark dermal denticles offer a chance to reconstruct reef communities over the last few thousand years, while isotopic analyses can describe the changes in environments. These data help reveal the relative roles of natural changes in climates and human impacts on modern reef deterioration, provide clear and quantitative objectives for coral reef conservation, and reveal if ecological processes have changed significantly on modern reefs.

Rigorous quantitative sampling of fossil communities aligned with high-resolution paleoenvironmental reconstructions can reveal how environments constrain and select for different ways of making a living, and how environments shape the functioning of biological communities, leading to insights into ecological and evolutionary processes with potential insights into the how life will respond to future global change.

The isolation of the Atlantic from the high-nutrient Pacific Ocean during the Pliocene drove an ecological revolution in the Caribbean, providing opportunities for new life forms while causing the extinction of others. Isotopic profiling of marine gastropods helps us reconstruct seasonal changes in temperatures and nutrient sources in coastal Caribbean seas over the last 10 million years. We combine this information with large-scale sampling of fossil mollusks, corals, fish and other life to explore how benthic and nektonic communities evolved during these changes, and reveal the origin of the modern Caribbean Sea.

Humans are somewhat unusual when it comes to predation because we tend to hunt the biggest animals. Continuous removal of the largest individuals in a population applies a selective pressure to reproduce at a smaller size, potentially causing evolution. The fossil and archeological records gives us the chance to observe changes in the life histories of socio-economically important animals before and during long-term harvesting. Our aim is to tease apart the relative importance of humans and natural ecological, physiological and evolutionary changes.

1995 B.Sc. (Hons.) Joint major Ecology & Earth Science, Liverpool John Moores University.

2000 Ph.D. Biological Sciences, Environmental Inferences from Recent and Fossil Bryozoans, University of Bristol.

Figuerola B, Grossman E, Lucey N, Leonard N, O’Dea A. 2021. Millennial-scale change on a Caribbean reef system that experiences hypoxia. Ecography. 10.1111/ecog.05606.

Dillon E, McCauley D, JM Morales-Saldana , ND Leonard, J-x Zhao, O’Dea A. 2021. Fossil shark dermal denticles uncover the pre-exploitation baseline of a Caribbean coral reef shark community. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2017735118.

Grossman EL, Robbins JA, Rachello-Dolmen PG, Tao K, Saxena D, O’Dea A. 2019. Freshwater input, upwelling, and the evolution of Caribbean coastal ecosystems during formation of the Central American Isthmus. Geology. doi.org/10.1130/G46357.1

Lin C-H, De Gracia B, Pierotti MER, Andrews AH, Griswold K, O’Dea A. 2019. Otoliths in coral reef sediments can help reconstruct past reef fish communities. PLoS ONE 14(6): e0218413. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218413.

Taylor LD, O’Dea A, Bralower T, Finnegan S. 2019. Isotopes from fossil coronulid barnacle shells record evidence of migration in multiple Pleistocene whale populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1808759116.

O’Dea A, Dillon E*, Altieri A, Lepore M. 2017. Look to the past for an optimistic future. Conservation Biology. doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12997.

Cramer K, O’Dea A, Clark TR, Zhao J-X, Norris R. 2017. Prehistorical and historical declines in Caribbean coral reef accretion rates driven by loss of parrotfish. 2017. Nature Communications, doi:10.1038/ncomms14160

O'Dea A, Aguilera O, Aubry M-P, Berggren WA, Budd AF, Cione AL, Coates AG, Collins LS, Coppard SE, Cozzuol MA, de Queiroz A, Duque-Caro H, Eytan RI, Farris DW, Finnegan S, Gasparini GM, Grossman EL, Johnson KG, Keigwin LD, Knowlton N, Leigh EG, Leonard-Pingel JS, Lessios HA, Marko PB, Norris RD, Rachello-Dolmen PG, Restrepo-Moreno SA, Soibelzon E, Soibelzon L, Stallard RF, Todd JA, Vermeij GJ, Woodburne MO, Jackson JBC. 2016. Formation of the Isthmus of Panama. Science Advances. 2, e1600883.

Finnegan S, Anderson SC, Harnik PG, Simpson C, Tittensor DP7, Byrnes JE, Finkel ZF, Lindberg DR, Liow LH, Lockwood R, Lotze HK, McClain CM, McGuire JL, O’Dea A, Pandolfi JM. 2015. Paleontological baselines for evaluating extinction risk in the modern oceans. Science 348: 567-570.

Taylor PD & O’Dea A. 2014. A History of Life in 100 Fossils. Natural History Museum/Smithsonian Books.

O’Dea A, Schafer M, Wake TA, Doughty D, Rodriguez F. 2014. Evidence of size-selective evolution in the Fighting Conch from prehistoric subsistence harvesting. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0159

Hacking the wood wide web

A disrupted mutualism sheds light on the dark web underneath the forest floor.

Gigante Peninsula, Panama

Chemical Ecology Microbial Ecology Connections in nature: Plants, Animals, Microbes and Environments Barro Colorado purple

purpleAn

underground

nutrient

market