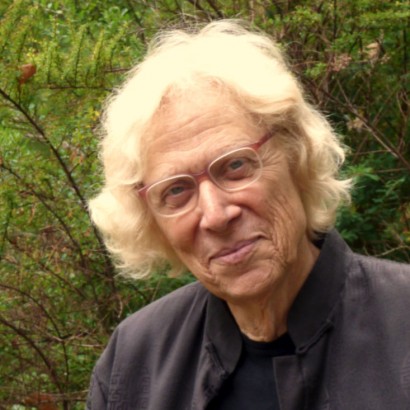

Matthieu Leray

The astonishing diversity of animals, algae and plants that live in the world’s oceans today would either not exist, or would exist in a very different form, if organisms had not interacted with microbial partners for millions of years. If we truly want to understand how biological diversity originated, how species coexist and how organisms cope with global changes, we must study the functional role of microbial partners and how microbes co-evolve with hosts.

In our lab, we conduct basic and applied research on (1) the mechanisms of coral reef resilience with the ultimate goal of finding ways to boost coral reef resilience; (2) the ecology of evolution of host-microbe interactions by leveraging the many sister species of fish, crustacean and mollusks that emerged after the closure of the Isthmus of Panama; (3) the population dynamics of endangered sharks and rays in the Tropical Eastern Pacific using non-invasive environmental genomics.

How do microbes support marine animal host acclimatization and adaptation to environmental changes?

The dynamic nature of microbes may provide a unique source of ecological and evolutionary novelty to support host responses to local (deoxygenation, pollution) and global environmental stressors (warming, acidification). The composition of microbiomes can shift rapidly through the loss, gain, or replacement of taxa. In addition, high rates of mutation and exchange of genetic material generate new genetic variants that may be better suited to novel conditions. We study how microbes influence host traits and how they are influenced by host traits over ecological and evolutionary time scales. We address these questions in a range of taxonomic groups, including corals, fish, crustaceans and mollusks.

How does ecological niche versatility contribute to the persistence of populations, species and communities on coral reefs of the Anthropocene?

The classical explanation for how many species can co-exist in species rich communities, such as coral reefs, is fine-scale niche partitioning of resources. High levels of morphological, behavioral and/or physiological specializations provide a refuge for species during periods of intense competition such as when ecosystems are in healthy states. Alternatively, specializations can make species vulnerable when resources become scarce. We study how coral reef associated fish and invertebrates with apparent specializations can switch to alternative resources as a mechanism to cope with changing environmental conditions. We investigate the consequences of niche versatility for the persistence of populations and the functional role of organisms on coral reefs of the Anthropocene.

Do marine animals and their associated microbes evolve in predictable ways?

Natural experiments, such as time-calibrated geological events with well-characterized environmental gradients, provide unique ecological and evolutionary contexts to understand how hosts and microbes have coevolved. Organisms on opposing sides of dispersal barriers follow separate evolutionary trajectories under the influence of local environmental conditions. We are leveraging a natural experiment, the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, to investigate how similar features arise in different organisms in response to experiencing similar selective pressures.

How do human activities affect the distribution, life history strategies and the functional roles of sharks and rays in the Tropical Eastern Pacific?

Many vulnerable shark and ray species, use mangrove-fringed bays and estuaries of the Tropical Eastern Pacific (TEP) as nurseries and feeding grounds. However, the persistence of these populations is threatened due to habitat loss, unregulated fishing pressure and pollution that impact them directly as well as their food source. The implementation of effective management strategies requires high frequency time series data (such as monthly or seasonal population size estimates) that traditional methods such as mark-recapture, acoustic and satellite tagging cannot provide effectively because they are time-consuming, expensive, and often invasive. We develop and apply non-invasive environmental DNA (eDNA) genomic techniques to scale up our understanding of shark and ray population dynamics for conservation.

M.Sc. University Pierre and Marie Curie, Paris 6, France, 2008

Ph.D., University Pierre and Marie Curie, Paris 6, France, 2012.

** shared first authorship

Clever F, Sourisse JM, Preziosi RF, Eisen JA, Rodriguez Guerra EC, Scott JJ, Wilkins LGE, Altieri AH, McMillan WO, Leray M. 2022. The gut microbiome variability of a butterflyfish increases on severely degraded Caribbean reefs. Communications Biology In Press

Leray M, Knowlton N, Machida R. 2022. MIDORI2: A collection of quality controlled, preformatted, and regularly updated reference databases for taxonomic assignment of eukaryotic mitochondrial sequences. Environmental DNA. 0, 1-14

Leray M**, Wilkins LGE**, Apprill A, Bik HM, Clever F, Connolly SR, De León ME, Duffy EJ, Ezzat L, Gignoux-Wolfsohn S, Herre EA, Kaye JZ, Kline DI, Kueneman JG, McCormick MK, McMillan OW, O’Dea A, Pereira TJ, Petersen JM, Petticord DJ, Torchin ME, Vega Thurber R, Videvall E, Wcislo WT, Yuen B, Eisen JA. 2021. Natural experiments and long-term monitoring are critical to understand and predict marine host-microbe ecology and evolution. PLoS Biology. 19, e3001322

Johnson MD**, Scott JJ**, Leray M**, Lucey N**, Bravo LMR, Wied WL, Altieri AH. 2021. Rapid ecosystem-scale consequences of acute deoxygenation on a Caribbean coral reef. Nature Communications. 12, 1-12

Leray M, Knowlton N, Ho S, Nguyen BN, Machida R. 2019. GenBank is a reliable resource for 21st century biodiversity research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116, 22651-22656

Wilkins LGE**, Leray M**, Yuen B, Peixoto R, Pereira TJ, Bik HM, Coil DA, Duffy JE, Herre EA, Lessios H, Lucey N, Mejia LC, O'dea A, Rasher DB, Sharp K, Sogin EM, Thacker RW, Vega Thurber R, Wcislo WT, Wilbanks EG, Eisen JA. 2019. Host-associated microbiomes drive structure and function of marine ecosystems. PLoS Biology 17, e3000533

Leray M, Alldredge AL, Yang JY, Meyer CP, Holbrook SJ, Schmitt RJ, Knowlton N, Brooks AJ. 2019. Dietary partitioning promotes the coexistence of planktivorous species on coral reefs. Molecular ecology 28, 2694-2710

Leray M, Ho S-L, Lin J, Machida R. 2018. MIDORI server: a webserver for taxonomic assignment of unknown metazoan mitochondrial-encoded sequences using a curated database. Bioinformatics bty454

Leray M, Knowlton N. 2016. Censusing marine eukaryotic diversity in the twenty-first century. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 371,20150331

Leray M, Meyer CP, Mills SC. 2015. Metabarcoding dietary analysis of coral dwelling predatory fish demonstrates the minor contribution of coral mutualists to their highly partitioned, generalist diet. PeerJ 3,e1047

Leray M, Knowlton N. 2015. DNA barcoding and metabarcoding of standardized samples reveal patterns of marine benthic diversity. Proceediengs of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112,2076-2081

Leray M, Yang JY, Meyer CP, Mills SC, Agudelo N*, Ranwez V, Boehm JT, Machida RJ. 2013. A new versatile primer set targeting a short fragment of the mitochondrial COI region for metabarcoding metazoan diversity, application for characterizing coral reef fish gut contents. Frontiers in Zoology 10,34