Q?Bus begins its

journey around

Panama

Undeniable

Science and universal education

for tackling climate change

Panama

Text by Leila Nilipour

The world economy is based on increased population and consumption, and education has an important impact on reducing this

To many, Steven Paton is known as Dr. Doom, because of his startling predictions about the future presented whenever he gives a public talk on climate change. What the director of the long-term physical monitoring program at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) typically shares is not encouraging, but it is based on his career collecting data in Panama.

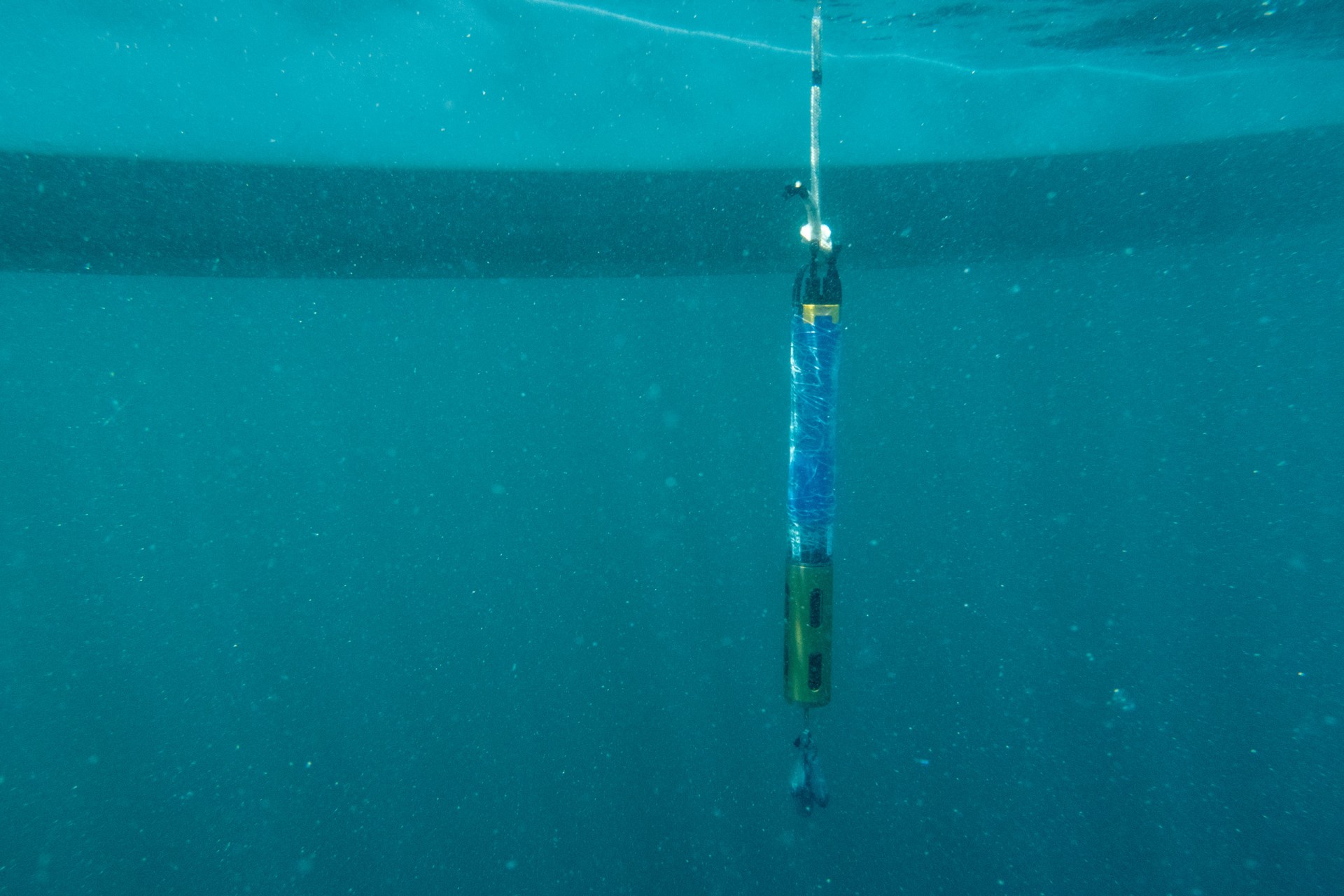

Beginning in 1972, the environmental monitoring program has been running for almost half a century, and Paton has been involved in it for three decades. Keeping track of environmental parameters all over Panama, in both land and ocean, allows researchers to understand how things used to be and how they are changing.

“You don’t know what you’ve lost if you haven’t monitored it,” says Paton. “And how can we protect what we don’t know?”

The environmental data collected by STRI is available to the public on the physical monitoring website, including rainfall data collected by the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) in the Panama Canal Basin for the past 140 years.

All this information, when analyzed, reveals plenty about the local state of affairs. In Panama, climate change is evident. Temperatures have increased significantly at several of the STRI’s climate monitoring stations. At Barro Colorado Island, for example, nighttime temperatures have gone up by around 2C degrees since 1972, while daytime temperatures have gone up by about 1C degree. Ocean temperatures are also on the rise.

Sea level is rising about 1.5 mm per year in the Bay of Panama, whereas in the Guna Yala archipelago, in the Caribbean, data from the University of Hawaii’s tide station show increases in the order of around 6 mm per year during the last seven years. Many of those islands are less than half a meter above the high-tide line and may cease to exist by the end of the century, possibly driving a change in the identity of the Guna people from an island- to a land-based culture.

Rainfall patterns are also shifting. According to data from the Panama Canal Authority, the last two decades witnessed eight of the 10 largest storms and the two driest years in the past 140 years since measurements have been taken in the Panama Canal Area. In Panama City, the combination of development, sea-level rise and large rainfall events will almost certainly lead to more frequent flooding.

“Extreme droughts not only affect Panama Canal business, but they endanger our water supply. For agriculture, too little or too much water also has major effects,” says Paton.

Government programs to develop coping mechanisms for what is to come benefit from accurate environmental monitoring information. For example, knowing which shores are eroding and how quickly will allow the government to dedicate more resources to help mitigate the most dangerous scenarios.

Paton is also involved in mangrove research and conservation activities and hopes that his efforts will help decision makers understand the value of increased investment in mangrove restoration and conservation. Activities by him and many others in Panama have shown the importance of mangroves for carbon absorption and the protection of shorelines.

What else can be done?

Educating the population. The world’s economy is based on supply and demand. As population increases so does consumption and strain on our planet’s resources. Per statistics from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo in Panama, among the 30-34-year-old women who gave birth to their 5th child in 2018, only less than 1 percent had postgraduate studies compared to the 20 percent who did not have an elementary school education. These statistics support the fact that education, especially of women, can help mitigate climate change in multiple ways.

Other individual decisions, such as going car-free or eating a plant-based diet, help reduce personal carbon emissions. Citizens may also choose to support environmentally conscious government representatives.

Another option is ‘carbon-offset schemes’, which allow individuals and companies to invest in environmental projects around the world in order to balance out their own carbon footprints. For example, paying a landowner to maintain his land forested instead of cutting down all the trees for cattle pasture.

Considering the potential impact of reducing cattle production is also important. Cows are very inefficient at converting what they eat into protein, and cattle ranching contributes heavily to climate change through deforestation and cow burps and gases, which emit the greenhouse gas methane. In their report “Estrategia Nacional de Cambio Climático 2050,” the Ministry of Environment (MiAmbiente) attributes about one-quarter of carbon emissions in Panama to livestock.

“In the tropics, one of the biggest reasons for deforestation is cattle ranching or soybean crops, a lot of which is used as food for cattle”, Paton says.

Most scientists would agree that substituting plant-based protein sources, such as beans, legumes and nuts, for beef can be environmentally friendlier and healthier. Other animal protein sources that are less damaging to the environment include chicken, fish, pork and eggs. Researchers are also focused on developing alternative, lower-impact protein sources, based on algae, insects, microbes and fungi.

Are we doomed?

As teenage activist Greta Thunberg often says, we need to “unite behind the science” and understand that even if the world really achieved control of rising temperatures as established in the Paris Agreement, all the carbon dioxide that is already in the atmosphere will take hundreds or even thousands of years to leave the atmosphere.

The planet will remain warm, and the permafrost —the layer of ground that is permanently frozen— as well as many glaciers and the polar icecaps, will continue to melt long after temperatures have stopped increasing. And they will do so until temperatures return to pre-industrial age levels.

As the permafrost melts, it could potentially release vast quantities of methane, one of the worst greenhouse gases, further contributing to the global warming cycle. Loss of the glaciers and polar icecaps will significantly increase sea levels and, in the case of disappearing glaciers, jeopardize water sources for hundreds of millions of people.

At the turn of this century, about one billion people could be directly affected by sea level rise. The increased frequency and severity of droughts predicted by most climate change models will affect many more, potentially leading to the mass migration of tens of millions of people.

“For me that’s going to be the moment everybody will realize society has to reinvent itself, because you can’t have millions of economic migrants without creating a great impact,” Paton concludes.

Although there have been several periods in the last 40 million years where the temperature has gone up, it never occurred so quickly, and ecosystems had enough time to adapt. If we really want things to improve, science can provide the necessary tools to go beyond individual actions and make the radical, large-scale changes required to stop current carbon dioxide production rates in the next 20 years.

*Unfortunately, the global covid-19 pandemic is currently affecting our ability to continue monitoring environmental and ecological processes throughout the isthmus of Panama*