Pseudoscorpions: Little guardians of crevices (public talk in Spanish)

Seeds for

a future

A course to learn about the

biodiversity of our forests

by Vanessa Crooks

Through a course in dendrology, the study of the taxonomy of woody plants in the absence of flowers or fruits, two experts in forest diversity seek to leave a legacy of knowledge for future generations.

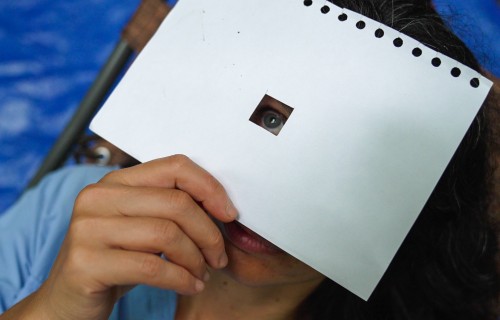

Tools such as iNaturalist, PlantSnap, and others that use artificial intelligence (AI) offer the ability to identify plants and trees from a photo. But how accurate can it be, when there are so many details that distinguish each species?

There is a lot to analyze in order to identify a plant or tree: for example, the shape and edge of the leaf, how the leaf looks from underneath, the arrangement of the leaves in reference to the stem, its nerves or veins, the texture, the smell, color, thickness, and much more.

Differentiating each species helps to keep an accurate record of forest biodiversity and how it changes, which allows us to understand a little more about forest dynamics. In Panama alone there are about 224 families of plants, which until 2004 totaled 8,582 species of vascular plants, and today could be around 10,000.

Because of this, the ability to identify and classify plants takes a lot of practice and study. At the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama, ForestGEO scientific research technicians Salomón Aguilar and Rolando Pérez are the go-to experts, both to identify species and to learn what it takes to develop this skill.

"This is a process that is sometimes not understood, how difficult it is to train a person in the methodology," says Pérez. "That's not a matter of one day, it's a matter of years."

"The fieldwork is what produces the methodology," Aguilar says. "Many strictly follow what the books say, but the field offers a lot more that cannot be found in books. What you can find in books actually comes out of field practice."

Both have been working with STRI since 1985 and 1986 respectively; they began their careers working alongside STRI scientists Robin Foster and Stephen Hubbell, who established the 50-hectare plot, a forest monitoring plot on Barro Colorado Island, in 1981. A long-term monitoring project is carried out on this plot, the tree census that is takes place every five years, which provides invaluable knowledge about ecology, taxonomy and forest dynamics.

Pérez and Aguilar have directed and supervised these censuses since 1995. They have also carried out floristic studies in many places in Panama, and among their botanical collections are records of some species of trees new to the country's flora.

With nearly 40 years of work with Foster and Hubbell and others, such as STRI research associate Richard Condit and Panamanian botanist and STRI scientist Mireya Correa (R.I.P), Pérez and Aguilar have accumulated valuable knowledge and experience of how to identify plants, and what they tell us about forests.

For this reason, they decided to create a dendrology course. Dendrology is a subcategory of botany specializing in the characterization and identification of woody plants or tree plants, which include trees, shrubs, and lianas.

The dendrology course group visited a trail in Altos de Campana, in Panama West, to study the species present in the mountainous areas of the country.

Credit: Jorge Alemán, STRI

"There used to be two well-marked branches of taxonomy: taxonomists-taxonomists and taxonomists-dendrologists," explains Pérez. "Robin Foster was not a taxonomist, he was an ecologist, but he had been so dedicated to the identification of plants, that he was respected. And there were traditional taxonomists such as Mireya Correa, that, if there are no flowers or fruits from the plant, it cannot be identified, you must consult a registry or book, compare it with the herbarium. They were the two trends, and we grew up in the traditional one. But when we met Robin, he told us 'yes we can'. Little by little, the myth that only with flowers and fruits can species be identified was being put aside."

Dr Robin Foster attached great importance to precise species identification for ecology, and he extensively catalogued BCI plants. When he and Hubbell created the 50-ha plot, they also established a standard method for conducting forest censuses, which is used in all plots in Panama and ForestGEO, the global forest observation network that is now located in more than 78 sites around the world throughout the Americas, Asia, Africa, Oceania and Europe.

As part of ForestGEO, Pérez and Aguilar have had the opportunity to visit and help establish these sites in different forests around the world, and to train hundreds of students, technicians, biologists and ecologists, to implement this method of measuring trees. But an important part of the method is the identification of each species being measured. Hence the importance of a dendrology course.

"The idea of the course originated from the fact that, for ForestGEO, the most difficult and the most important thing to be able to have field data is to have good field identification," says Pérez. "And that's been the challenge, because the diversity of tropical forests is so great that there are few botanists who can identify and contribute to having solid and rapid data."

Since 2005 they have had David Mitre as research manager. In addition to receiving plant identification training, and participating in plot censuses, Mitre has helped optimize data collection processes across the ForestGEO network, train new team members, and share the methodology in ForestGEO plots around the world. Pérez and Aguilar suggested to Stuart Davies, director of ForestGEO and a scientist at STRI, that Mitre would be a good candidate to replace them.

"Since Salomón and I are close to retirement age, we proposed to Stuart to do a course, to leave ForestGEO with a trained team," says Pérez. "So far there has been no need, because they come from ForestGEO and tell us 'I need someone who can identify plants'. But we have always tried to have courses, mainly for those who work with us. The people from Agua Salud, those from Helene Muller-Landau's forest ecology laboratory, have all been trained by us. We have been like a university."

"But you have to think about the staff, because some of us are getting old and this is a very hard job," he adds. "Also, you have to give young people a chance, and you have to train them."

Davies agreed to a course or workshop on tree identification, focused on ForestGEO technical staff and members of STRI's technical and scientific community. However, he suggested that some spots be opened for university students.

The invitation was announced on STRI's social networks; interested students would have to meet certain requirements on their resume. They chose students from state universities throughout the country, such as the University of Panama, Universidad Tecnológica, Regional Centers, UNACHI, and more, from careers such as plant biology and forestry engineering.

The course lasted four weeks, one week a month, from August to November 2024, and featured a theory and documentation section and another field trip section. Of the 224 plant families in Panama, the instructors chose 50 families and 420 tree species that they consider the most common and essential to teach during the course.

For the field trips, the instructors chose between protected areas where ForestGEO has plots, areas that present part of the families, genera and species that they studied in the theoretical classes, and areas distributed in different life zones and precipitation gradients, all easily accessible by a small bus and as close as possible to Panama City. They visited Gamboa and San Lorenzo National Park in the province of Colón, Chagres Park in Panama North, and Altos de Campana in Panama West.

"The goal is not only to look at the taxonomy, but also at the ecology of the species, which is like another source to understand taxonomic identification processes. We're trying to instill this in people during training," Aguilar says.

Before starting the trail tour in Altos de Campana, a low mountain area, the group stopped at the entrance; Pérez and Aguilar made a brief review of what they studied.

"We've already said that there are two major groups, vascular plants and nonvascular plants," Perez said. "Within the vascular plants, there are two groups: angiosperms and gymnosperms. This is one of the few gymnosperms native to Panama. It is a Podocarpus guatemalensis, it has a smell of resin, the leaves, with a single vein, always alternate..."

The students looked in detail at the leaf that Rolando was holding and took notes.

After the introduction, instructions and warnings, the group split in two. The students who were with Pérez went ahead on the trail. The other group, led by Aguilar, started closer to the entrance.

While collecting leaves to distribute among the students for analysis, Aguilar explained how he selects the plants: "I show them some that are very endemic to the site, so that they learn the term endemism, but I also select some that are widely distributed so that they know those that are both in the lowlands of the basin and in mountain areas."

"The first level objective of this course is for them to learn how to pinpoint plants by family," Mitre said as the students began their analysis of each sample. "The main thing is to recognize the structure by family. You're not going to spend all your time on the field, because that's costly. If the vast majority of plants can be grouped by family, a great job has already been done. And that helps you to defend yourselves anywhere in the world."

"It's a little slow, because you have to stop to examine, to do the description, all the diagnoses, progressively, and especially with new people," Aguilar said.

The group slowly advanced along the path until they joined up with the other group. Around noon, when it was time to return, it began to rain. Despite the weather and fatigue, the students were satisfied and enthusiastic.

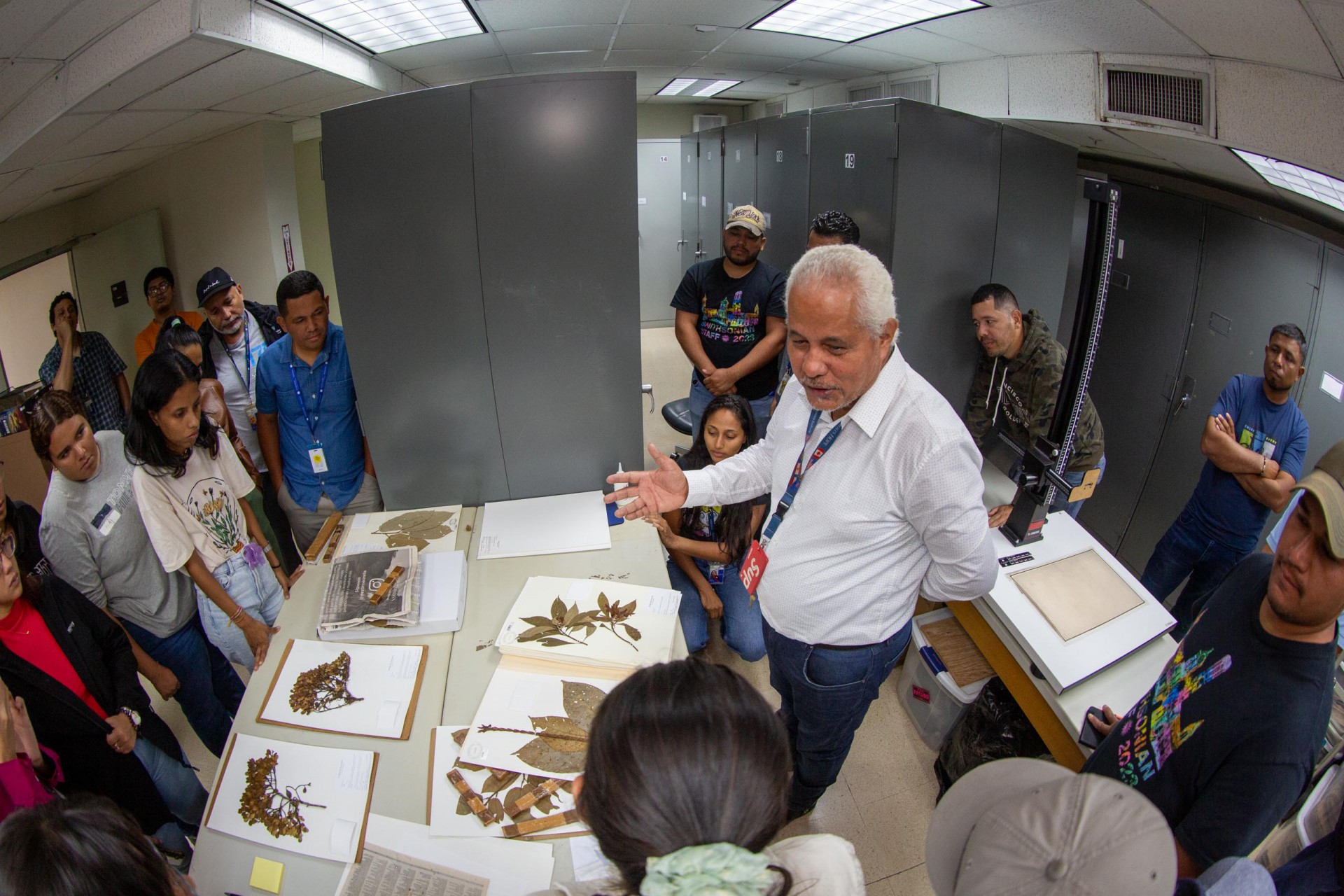

The course included a visit to STRI's herbarium, called SCZ Herbarium, at the Earl S. Tupper Library and Conference Center in Panama City. The herbarium's collection contains more than 6,000 specimens, and is an essential tool for verifying the plants that researchers find every time they go out on the field. STRI herbarium research technicians Ernesto Campos and Joana Sumich also participated in the course, the former as an instructor during herbarium visits and the latter as a student. Campos was recently part of the identification of six new plant species, including three from Panama.

"Herbariums are a basic tool for all of us," Perez says. "Even if you have experience, you can overlook things, and then you have to turn to the herbarium."

At the end of the course, participants filled out an anonymous survey to give their opinions of the course, what worked and what needed to be improved for future courses.

Another objective of this course is to make a formal publication of a field dendrology manual, based on the manual that the instructors developed for the students of the course.

"We are analyzing whether this course can be part of ForestGEO's annual work plan, it depends on the demand of interested participants," Mitre reveals. "We also hope to be able to open some spots for professionals who already exercise their careers in related areas."

In the planning of this year's course, instructors are incorporating material from dry forest flora. Among the places they have chosen for the next field trips are the Metropolitan Natural Park, Soberania National Park, San Lorenzo National Park, and the Barro Colorado Natural Monument.

The invitation for the next course will be announced between June and July 2025, through STRI's social networks.