Q?Bus begins its

journey around

Panama

The queen

of the forest

Unlocking forest biodiversity: What can Virola nobilis trees teach us about tropical ecology?

Panama

Text by Leila Nilipour

Cover photo by Christian Ziegler

Virola trees in Panama are defying a well-known hypothesis from the 1970s regarding tropical biodiversity, revealing how genetics and the environment shape pathogen communities and seedling survival in tropical forests

Why is tree biodiversity so high in tropical forests? According to the famous Janzen-Connell hypothesis from the 1970s, the answer lies in the trees’ natural enemies. Pathogens in the soil—microbes like fungi—have their darlings. They may attack their favorite tree species and not even glance at the ones around them. This preference puts the seeds falling near the parent tree at greater risk: their natural enemies are at their doorstep.

Their best chance of survival lies in getting carried away by seed dispersers like birds or monkeys, leaving space behind for seedlings of other species to grow near their parent tree. As they get dispersed, trees of the same species grow distant from one another. However, in the middle of the Panamanian forest, research on one tree species —Virola nobilis— has been challenging this hypothesis.

At first glance, Virola complies with the Janzen-Connell hypothesis. The large and beautiful tree attracts many animals who enjoy munching on the fleshy red layer of its seed, helping distribute it around the forest by regurgitation or defecation. However, Virola doesn’t necessarily grow away from its parent tree. On Barro Colorado Island (BCI), in the Panama Canal, they are seen growing close to each other.

The NSF-funded project, “Genes to ecology in tropical trees: how sharing resistance gene alleles affects pathogen transmission and growth,” a collaboration between the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), Penn State University, and the USDA, is studying Virola trees on BCI to explore how variation in disease-resistance genes act as an additional tool for seedling survival in tropical forests. This idea is related to the way Virola reproduces.

STRI ecologist Erin Spear, a co-PI of the NSF project and lead scientist of a forest-focused disease ecology program generously funded by the Simons Foundation, explains that Virola trees have both male and female individuals, meaning that they rely on pollinators to reproduce. Hoverflies fulfill this crucial role, often carrying diverse genetic material from distant trees during pollination.

“We like to think of Virola as the queen of the forest,” says Spear, sitting in the middle of the forest on Barro Colorado Island as part of a video shot by Christian Ziegler and Victor Ammann.

Hernán Capador-Barreto, a postdoctoral fellow at STRI, underscores the exceptional nature of this forest for this type of research, particularly a 50-hectare plot in the heart of the island. This plot has been the focus of scientists who have meticulously tracked the growth of every tree within it for over 40 years.

“We can use all the [Virola trees in the 50-hectare plot],” said Capador-Barreto. “We know how they have been growing since the 1980s, where they are in space, and which trees are close to each other.”

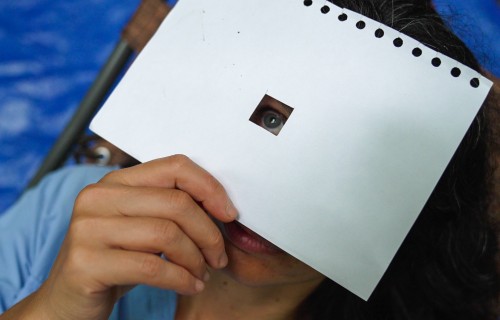

A video produced in Barro Colorado Island delves into a collaborative, BCI-based, NSF-funded research project called “Genes to ecology in tropical trees: how sharing resistance gene alleles affects pathogen transmission and growth”, which involves several STRI scientists.

Credit: Christian Ziegler and Victor Ammann

As part of their experiments, the researchers found that the pathogenic communities under individual Virola trees differed, and that sex influenced the composition of beneficial microbes. They also determined that many of these pathogens are “generalists” capable of causing disease in various plant species, not just on Virola, challenging an assumption of the Janzen-Connell hypothesis that host-specific pathogens are responsible for maintaining forest diversity.

Additionally, their findings revealed that a combination of genetic characteristics in the Virola seedlings and soil environmental conditions may significantly impact their likelihood of survival, hinting at the initial question of the NSF project: Do certain genes play a role in seedling susceptibility to forest pathogens?

Capador-Barreto emphasizes that these insights deepen our understanding of tropical forest dynamics and may shed light on the potential consequences of forest fragmentation.

“What happens when forests are fragmented, and pollen cannot move freely, or where animals cannot move seeds from one place to the other?” he wonders in the video.

Ultimately, this study advances our understanding of tropical forests by revisiting and re-envisioning traditional ecological ideas about the survival of tree seedlings close to their parent trees and others of the same species through the lens of improved understanding of key pathogens and the genetics of host resistance.