A comparison of colorful hamlets

from the Caribbean challenges ideas

about how species arise

Roost

Rulers

Small prey bully large

predators… and win

Text by Beth King

Tiny, fruit-eating bats take over the roost of larger, carnivorous bats at the edge of Panama’s Soberanía National Park.

Have you ever seen a chihuahua yapping at a German shepherd? Or a pair of songbirds heckling an eagle? Bullying happens in the animal world, and surprisingly, small bullies sometimes get their way. Researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) surveilling video recordings of bat roosts near Panama’s Soberanía National Park saw small fruit-eating bats evict larger carnivorous bats from the roost—predators known to consume them.

“During the height of the pandemic we couldn’t work in the lab or in the flight cages,” said Rachel Page, staff scientist at STRI, “but our cameras in the forest recorded sometimes very surprising bat behaviors. We saw small, fruit-eating bats attack and displace carnivorous bats that weigh twice as much as they do.”

The Seba’s short-tailed bat, Carollia perspicillata, weighs about as much as a strawberry. Whereas the fringed-lipped bat, Trachops cirrhosus, weighs about as much as an apricot. Both bat species are common in the American tropics. The smaller, short-tailed bats eat mostly fruit, whereas the fringed-lipped bats eat a wide variety of prey, from frogs to insects to smaller species of bats.

According to the team, who had never seen this phenomenon before, a tiny, feisty fruit bat could drive bigger bats out of the roost by heckling them: by “intensely vocalizing, rapidly flapping its wings, hitting the faces of the other bats with its wings, and flinging its body at the other bats,” a lesson from nature that may be relevant to our own geopolitical crises.

“After watching hundreds of hours of video, we have a whole new perspective on their lives,” said Gregg Cohen, STRI bat lab manager, who was the first to notice the behavior. As she analysed the video, Mariana Muñoz-Romo, STRI post-doctoral fellow who set up these field observations with Cohen and Page, recognized how lucky the team was to have captured this never-before-observed behavior.

“When Gregg told me that he had seen a little male Carollia bat displacing Trachops individuals in the roost, I was immediately fascinated. Upon analyzing the video, we realized that this recording is a gem, it teaches us something new about the social lives of these fascinating mammals, and how interspecies aggression takes place in nature,” said Muñoz-Romo.

Both bat species sleep in tree holes, caves, and culvert drainage pipes. Researchers built a series of tall, rectangular, concrete roosts – mimicking the hollows found in the trunks of trees – and these roosts were quickly colonized by a number of species of bats. The roosts were fitted with infrared video cameras and ultrasonic microphones, and, beginning in June 2020, recorded almost 300 hours of the bats’ private lives. On June 19th, they recorded the first of many, previously unknown, bat bedroom behaviors.

Two individual Seba’s short-tailed bats faced off with four adult and two juvenile fringe-lipped bats. The encounter started with the male short-tailed bat vocalizing aggressively toward the fringe-lipped bats, followed by rapid wing shaking, hitting and then throwing himself at the group. The male fringe-lipped bat defended his companions by vocalizing, displaying his wings and attempting to bite the aggressor. After the male fringed-lipped bat succeeded in biting the short-tailed bat’s wing, the short-tailed bat rushed the larger bats and beat the much larger male’s face with his wings.

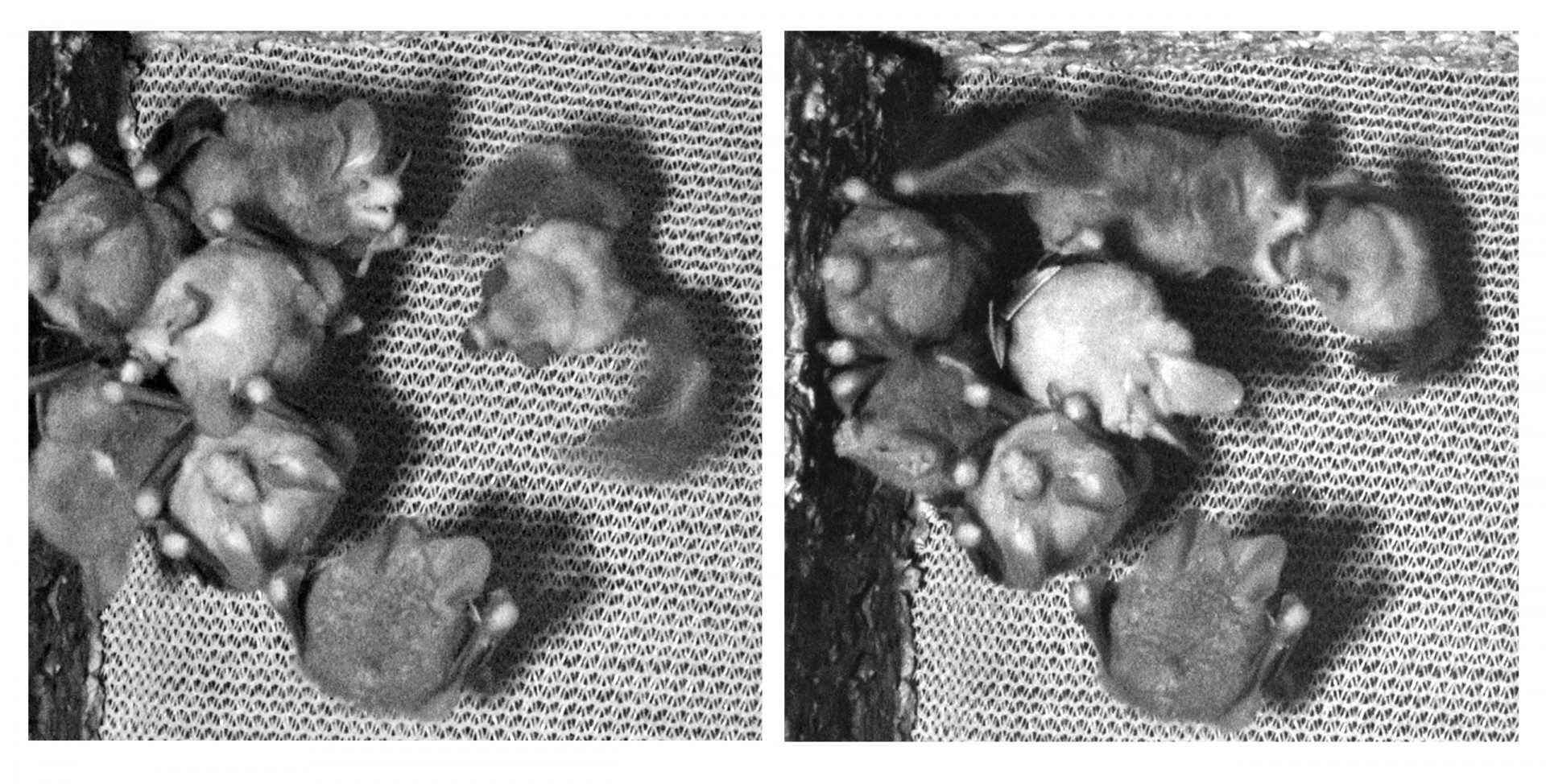

A Seba’s short-tailed bat faces off with four adult and two juvenile fringe-lipped bats. The encounter starts with the male short-tailed bat vocalizing aggressively toward the fringe-lipped bats, followed by rapid wing shaking, hitting and then throwing himself at the group (left). The male fringe-lipped bat (top left) defended his companions by vocalizing, displaying his wings and attempting to bite the aggressor (right). Credit: Video stills_Mariana Muñoz-Romo.

After about four minutes of abuse, the male fringe-lipped bat left the scene, and most of the bats in his group followed. A lone female fringe-lipped bat continued to hold out, attempting to bite her aggressor. Finally, after more than six minutes, she ceded the roost to the short-tailed male who began to groom himself and was then joined by his female roostmate.

Later in the year, the team saw this interspecies conflict two more times, with the same outcome and were intrigued about the reason for the interaction. The two bat species often share the same general roosting area. The Seba’s short-tailed couple could have used the three other corners of this roost or several other experimental roosts nearby. Why did the Seba’s short-tailed bats drive out the fringe-lipped bats? Was this corner especially comfy? Did it have a particular microclimate that the bats like? Was this a way of warning the bigger bat species not to mess with them within a shared roost?

"Discovering unknown behaviors like this gives us the feeling that we know so little about the social behavior of bats,” said Muñoz-Romo. “A lot of work is still waiting for us as we begin to understand bats’ fascinating private lives. Despite the hard work of watching hundreds of hours of recordings, devoting myself to this task is simply captivating.”

The study was supported by the FaB 5 Fund and by a National Geographic Explorer grant to Mariana Muñoz-Romo.

Reference: Muñoz-Romo, M, Cohen, G, and Page, R.A. 2022. Place your bets: small prey faces large predators. Behavior. Doi: 10.1163/1568539X-bja10157