A comparison of colorful hamlets

from the Caribbean challenges ideas

about how species arise

Living

Color

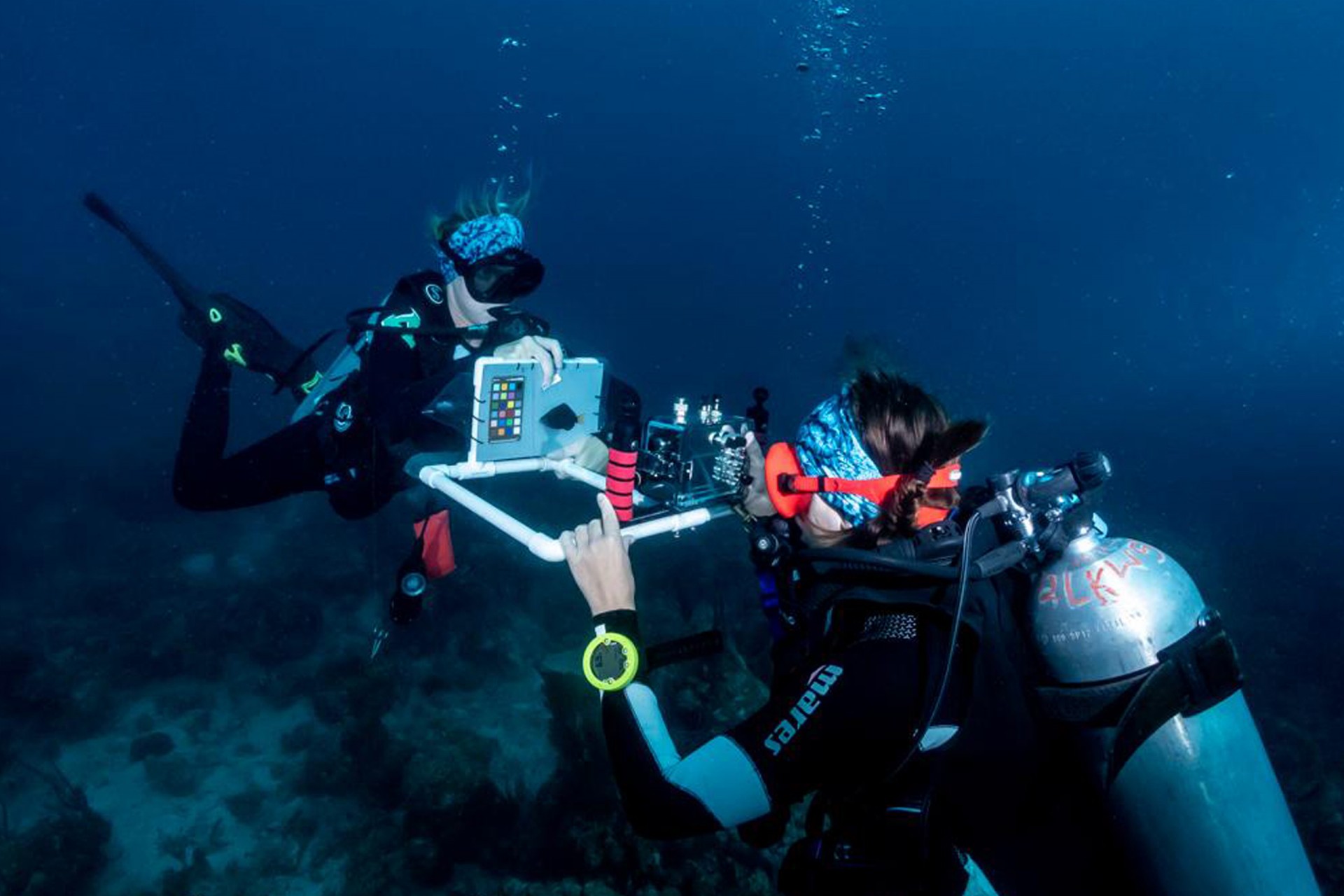

A new underwater photo studio yields pixel-scale fish color pattern data

Panama

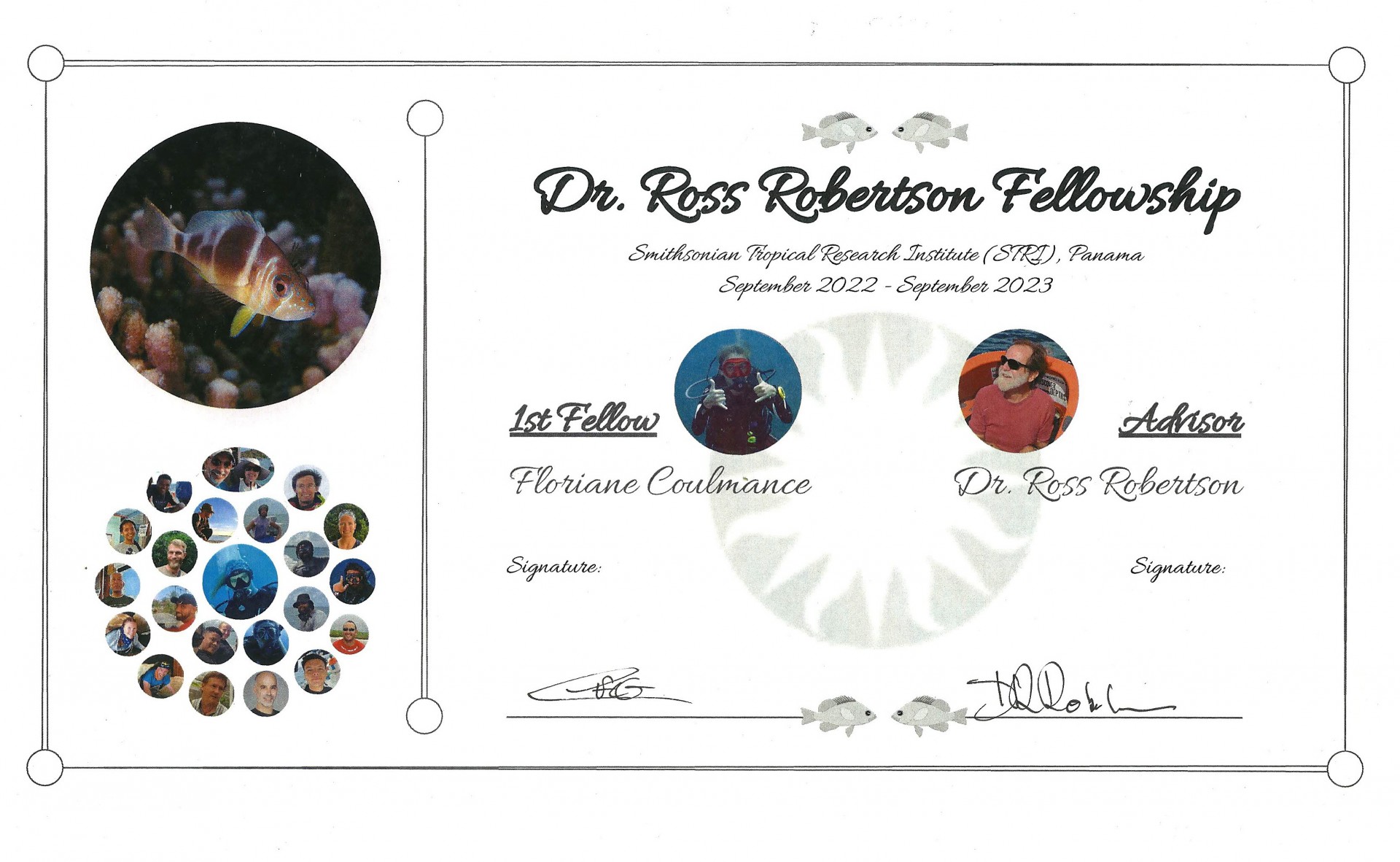

The first winner of the D. Ross Robertson Postdoctoral Fellowship for Field Studies on Neotropical Reef Fishes, Floriane Coulmance, tests a new, underwater camera system to study the connection between hamlet color patterns and genetics in fish from four countries around the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.

Reef fish speak in color patterns. Like shimmering jewels, hamlets flit through coral reefs, signaling “I’m your type,” to potential suitors. Researchers use color patterns to tell hamlet species apart—the first step as they study climate change or evolution. But these complex color patterns vary under different conditions and fade quickly when fish are removed from the water. And humans perceive color differently than fish do. To overcome these challenges, Floriane Coulmance, at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) set up a completely underwater, digital photo studio. Her innovative work is proof-of-concept for highly detailed, digital color analysis in fish.

“To ID hamlets, biologists have always described their colors,” said Floriane, the first winner of the D. Ross Robertson Postdoctoral Fellowship for Field Studies on Neotropical Reef Fishes. “But we needed to compare color patterns under natural light conditions—in both murky and clear water—and to match up each color pattern with its genetic code. So we set up an underwater photo studio that captured raw digital images that we could compare pixel by pixel: this is the first study of its kind done completely underwater.”

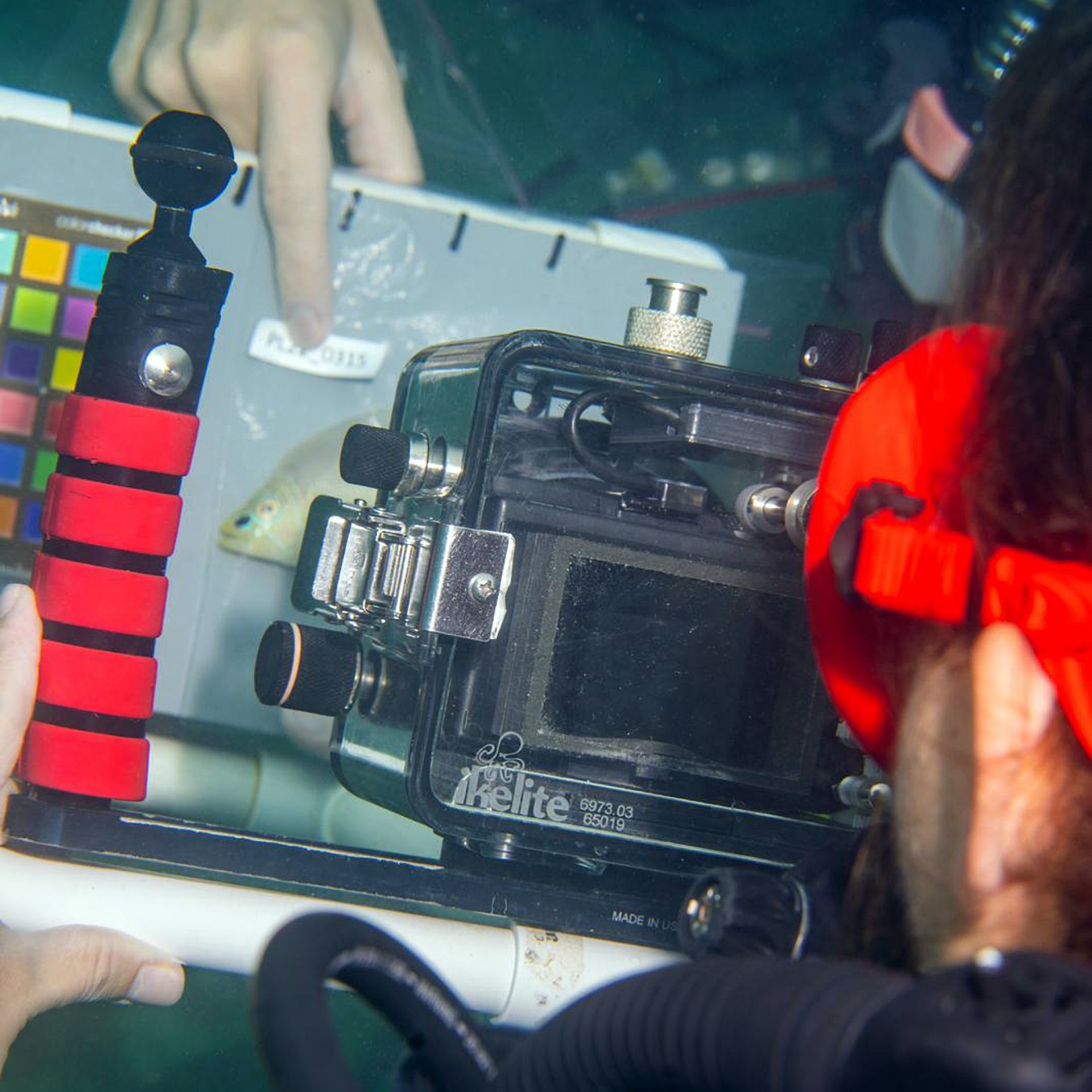

Hamlets are all the same shape, but different individuals have different color patterns. After catching a fish and placing it in a plastic bag, the divers position it against a white background next to a color chart and snap its photo with a mirrorless Canon EOS M3 camera against a plain white background with a color chart on one side. Credit: Sara Richter.

Photographing fish underwater in this innovative underwater photo studio is a two-person job. Credit: Sara Richter.

In collaboration with colleagues from Israel, Germany, and France, Floriane tested this system on 113 hamlets from the Caribbean. She compared fish color patterns and the genes that code for them as part of her doctoral work with Oscar Puebla, Research Associate at STRI, researcher at the Leibnitz Centre for Tropical Marine Research and professor at the Institute for Chemistry and Biology at Oldenburg University in Germany. She came back to STRI as a fellow to expand the study to more hamlet species in the genus Hypoplectrus across the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

Going fishing

When she received her fellowship, the clock started ticking. Floriane flew to the Smithsonian’s Bocas Research Station in Bocas del Toro, Panama, where she worked out all the kinks in the system with Melanie Heckwolf, a post-doctoral fellow in Owen McMillan’s lab at STRI, and Jakob Gismann, PhD student at the University of Groningen. Their first challenge was to learn to catch the fish.

“We tried to net them, but it’s incredibly difficult to catch fish in a net while swimming through a reef with currents pushing you around,” said Coulmance, “so we shifted to line fishing: baiting a hook and then dangling it over the reef until we caught the fish we were looking for.”

Next, they placed each fish in a sandwich bag and photographed it with a mirrorless Canon EOS M3 camera against a plain white background with a color chart on one side. Photographing fish underwater using this set-up is a two-person job, and Floriane realized that Melanie’s great help would be essential for the entire project. Throughout the next year, Floriane and Melanie photographed 500 fish at sites in each of four countries: Panamá, Trinidad and Tobago, St. John (U.S. Virgin Islands), and Veracruz (Mexico).

Close up of underwater photo studio. Credit: Andre Hernandez.

“We couldn’t have done it without the amazing group of people who helped us,” exclaimed Floriane. Ross Robertson, emeritus STRI staff scientist who endowed this fellowship, is still very active; he knows academics and his enthusiastic underwater-photographer friends know people at dive shops around the Caribbean.

The first stop, Tobago, went very well with the help of two dive masters, Randy Davis and Shomari Charles, and fisherman Irwin Nicholls (aka Maestro). It rained a lot, and some dives had to be cancelled after landslides from the steep island slopes muddied the water. But everyone wanted to help the “intriguing researchers” catch fish, and they were able to catch 69 fish in just a few days. On this trip they saw one bluelip hamlet, a rare species for Tobago (recently described in a paper co-authored by Floriane) right at the end of a dive, but they had to surface before catching it. They went back several times to the same site, but never saw it again.

Then they moved on to St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. This time they were joined by the award-winning volunteer photographers, Allison and Carlos Estapé and their friends Andre Hernandez and Serenity Mitchell from a local dive shop, and photographers Alasdair Dunlap-Smith, Lee and Sarah Richter. This trip was also an enormous success, and they caught and photographed 136 fish, half of them in the first three days. “St John was an extraordinary place to work,” said Floriane, “not only were there a ton of hamlets but we were supported by an amazing team of fish enthusiasts.”

Diving team in St. John, Virgin Islands. The help of local dive shops and volunteer divers and photographers made a challenging project much easier. From left to right: Carlos Estapé, Lee Richter, Melanie Heckwolf, Andre Hernandez, Floriane Coulmance. Credit: Allison Estapé.

Maestro’s boat (pink) – “The Amazing Grace” - at sunset in Tobago. Credit: Floriane Coulmance.

Their last trip, to Veracruz in Mexico, was a bit more challenging because some of her team got sick, because everyone except the researchers spoke mostly Spanish, and because Floriane was pressed to wrap up the project, facing time and budget constraints. But once again, colleagues came to the rescue: Omar Dominguez-Dominguez, professor at the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás Hidalgo (UMSNH) and his student Karim Awhida helped with the logistics, with the negotiations with the dive shop and mostly with catching fish and taking pictures. In the end, they were able to photograph 60 hamlets representing the two prominent species of this area.

At their base at STRI’s Bocas del Toro Research Station, where they lived for most of the year, Floriane and Melanie did an enormous amount of work, exploring a huge part of the archipelago, and photographing and collecting tissue samples for more than 200 fish.

Barred hamlet (Hypoplectrus puella) from Bocas del Toro. Credit: Floriane Coulmance.

“It’s thanks to local knowledge from boat drivers to local dive guides, and the amazing support we got from station staff, that we were able to explore and find new interesting reefs and rare hamlets,” said Floriane. In the archipelago, they found three rare hamlets: one—the masked hamlet—had not been recorded in the area for more than 10 years.

Working in four countries in a year required complex logistics and Floriane will be eternally grateful to staff from the STRI permits office, as well as her collaborators who smoothed the way at each research site.

Back in the lab

Once back in the lab, photographs and tissue samples can be analyzed and interesting questions arise: What role does the striking diversity of color patterns displayed by reef fishes play? How can researchers analyze these color patterns objectively and quantitatively and how do genes determine color patterns?

Floriane continues to uncover the genetic bases of color pattern diversity in a group of reef fishes using this completely new method. Furthermore, her research sheds light on how color pattern diversity arose rapidly from both a color pattern (phenotype) and a genetic (genotype) perspective, a question that other evolutionary biologists in the tropics—like the big group of butterfly researchers working with STRI staff scientist Owen McMillan in Gamboa, Panama—are also fascinated by. At times that are characterized by high extinction rates, seeing the flip side of the coin—how diversity arises—has become a critical question.

Genetic analysis has become a much more exact science during the last two decades. The most powerful use of genetic information (genotype) is when it can be directly matched up with the observed characteristics (phenotype). Floriane’s new system provides pixel by pixel details about color (phenotype), much more information than qualitative researcher descriptions (black stripes, yellow tail fin, etc.) and makes it possible to predict exactly which genes control which characteristics. We humans are biased by our own abilities to perceive and interpret information. Sometimes animals perceive and interpret information in very different ways. A computer analysis is less biased and may yield insights that we miss.

The underwater photo studio made it possible to predict where on the fish body a particular genetic variant affects color pattern and at which intensity.

Differences in DNA Matching color pattern (phenotype) with genetic code (genotype)

The parts of the fish body that are affected by the variant in the LG12 region of the genetic code.

Credit: Floriane Coulmance.

What’s next?

Floriane bubbles with enthusiasm, obviously the key to achieving so much in a single year. Her background is hands-on science: a bachelor’s degree at the Learning Planet Institute in Paris; a semester in marine biology, zoophysiology and molecular biology at Nord University in Norway; then an internship in Roscoff Marine Station, France, studying dinoflagellates. During her masters’ degree at Imperial College in London, she found herself in the Maldives studying mosquitos, but became hooked on marine science after taking diving courses on the islands. Soon afterwards, she began her PhD with Oscar Puebla at ZMT.

“If I could dive every day for the rest of my life, I would do it,” she says.

Floriane Coulmance, D. Ross Robertson and Melanie Heckwolf.

Certificate of accomplishment to celebrate everyone that participated to the success of Floriane’s project as the first D. Ross Robertson Post-doctoral fellow. Credit: Floriane Coulmance.

Floriane is driven by fundamental science questions such as: what fueled the current observed diversity of reef fish both in terms of evolutionary history and ecology, and what can we learn from this for the future of the oceans and the planet? In a rapidly changing ocean environment, preserving the potential to generate diversity is essential. Ecosystems rely on diversity to be resilient and resistant to change.

With the number of photographs generated and tissue collected during her fellowship year, Floriane will be able to explore variation in color patterns not only between species but within a single species, thus establishing a basis for the study of the eco-evolutionary significance of color pattern in all reef fishes.

Reference: Coulmance, F, Akkaynak, D, Le Poul, Y, Höppner, MP, McMillan, WO, Puebla, O. 2023. Phenotypic and genomic dissection of colour pattern variation in a reef fish radiation. Molecular Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17047

Puebla, O., Coulmance, F., Estapé, C. J., Estapé, A. M. and Robertson, D. R. (2022). A review of 263 years of 1123 taxonomic research on Hypoplectrus (Perciformes: Serranidae), with a redescription of Hypoplectrus affinis (Poey, 1861). Zootaxa 5093, 101–141. 10.11646/zootaxa.5093.2.1