A comparison of colorful hamlets

from the Caribbean challenges ideas

about how species arise

Profile:

Harilaos

Lessios

Calibrating

evolution

Naos Island, Panama

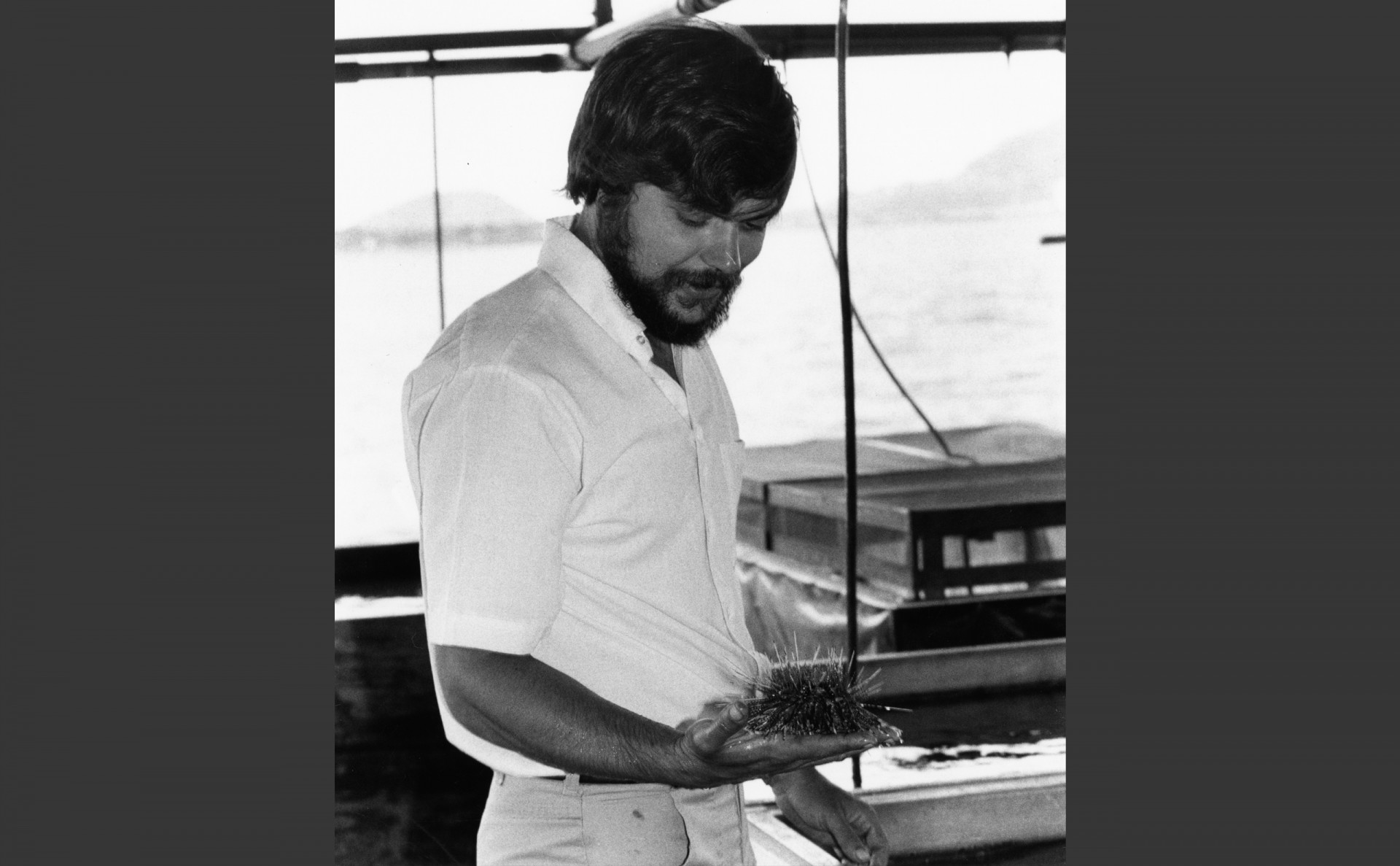

Veteran Smithsonian evolutionary biologist Haris Lessios has made major contributions to the understanding of how new marine species arose following separation by the Isthmus of Panama.

Harilaos Lessios, who is better known to his colleagues as Haris, is of Greek origin and graduated from Harvard (B.S.) and Yale (Ph.D.). Haris uses molecular techniques combined with development and biogeography to understand speciation in sea urchins. Perhaps no other scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute has used the creation of the Panamanian Isthmus to such effect in their research.

Lessios argues that since sea urchins have external fertilization and live in the ocean, their gene pool usually needs to be separated by a physical barrier — like the Isthmus of Panama – for gametes to be reproductively isolated on either side allowing new species to form. His 2005 classic paper “the Great Schism” documents the different molecular trajectories of 34 lineages of invertebrate sister species separated when the isthmus formed and the Caribbean became so different from the Eastern Pacific.

In another major review with colleague Ross Robinson, he looks at speciation across a different barrier, namely the vast eastern ocean between species on the western and eastern margins of the Pacific. Haris and colleagues have especially focused on the evolutionary role of bindin, a protein in sea urchins that promotes attraction and adhesion of sperm and egg, a selective advantage for free swimming, externally fertilizing, ocean species.