Túngara frog tadpoles that grew up in the city developed faster but ended up being smaller.

Bound

by blood

Vampire bat bonding persists

from the lab to the wild

Panama

Bats moved from a captive colony back to a tree stayed with their friends.

Friendships are a key source of human happiness, health and well-being. Increasing evidence shows that similar relationships are important in many other animal species, including the blood-feeding vampire bat. According to a new study in Current Biology by researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), vampire bats form friendship-like social bonds that persist across a dramatic shift from the lab to the wild.

Vampire bats are highly cooperative. They regurgitate blood to feed hungry bats in their social network, even to unrelated adults.

“For several years, we have been doing experiments on food sharing in kin and non-kin vampire bats in captivity, but we also wondered if these stable cooperative relationships were largely an artifact of being in captivity,” said Gerald Carter, research associate at STRI and professor of biological sciences at the Ohio State University.

Carter found that putting the bats into constant captive association made them more likely to share food. “But we wanted to test if these relationships would persist if the bats were back out in the wild where they could choose to associate with anyone and go anywhere. In other words, are we experimenting with real social bonds that would persist in nature?”

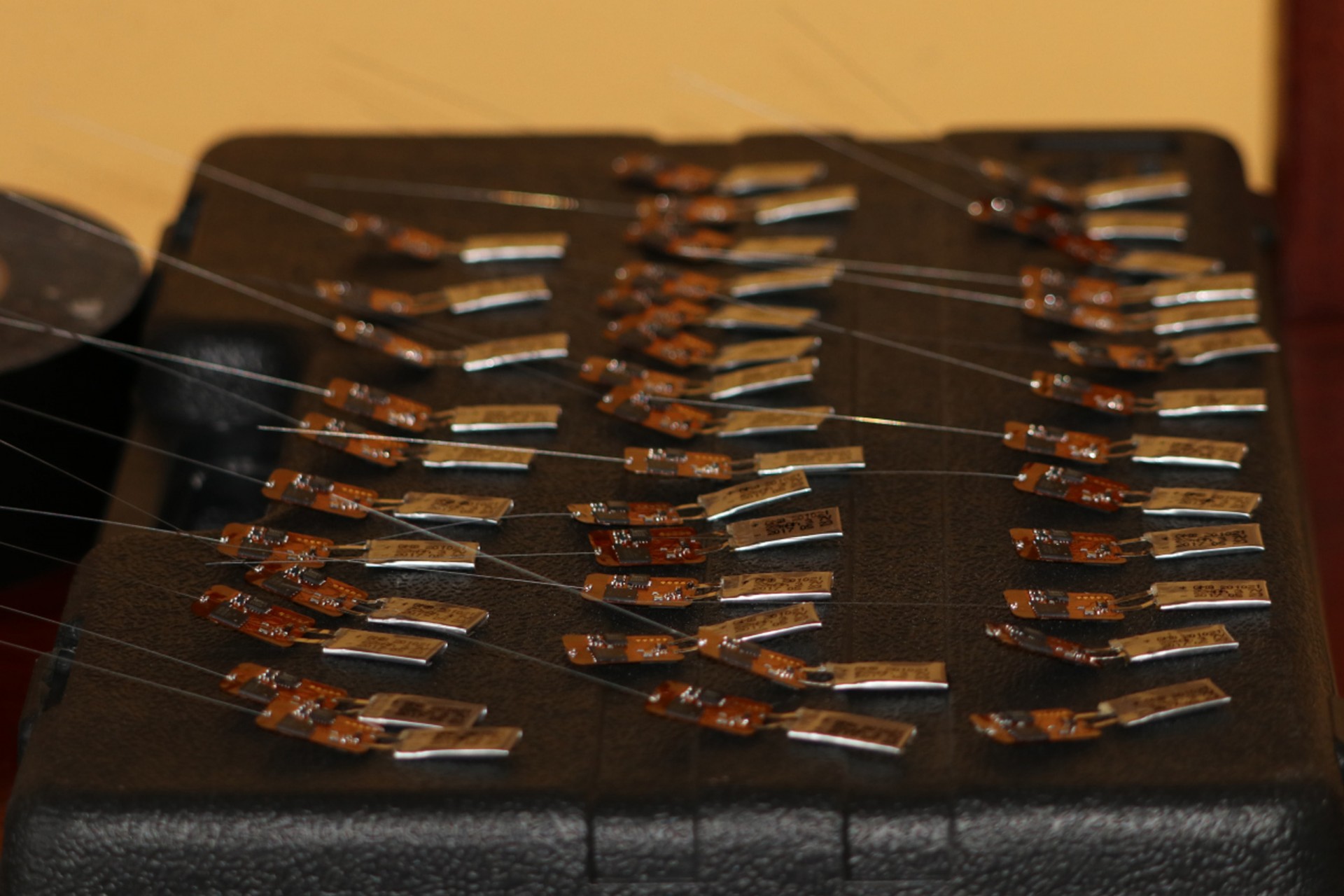

To find out, Carter teamed up with biologist Simon Ripperger, who developed a new technology for tracking the social networks of wild bats in collaboration with a team of engineers. They built proximity sensors, miniaturized computers weighing less than a penny, that attach to each bat. Ripperger and Carter used these tiny high-tech backpacks to map out the bats’ social network in the wild.

After studying cooperative relationships between bats in captivity for almost two years, the biologists attached the sensors to the bats and released them back into their natural colony, a hollow tree in a Panamanian cattle pasture. They also attached sensors to a random control group of bats caught from the same colony. The sensors logged social encounters every two seconds for more than a week, resulting in a huge dataset showing daily changes in the bats’ social networks.

“A few years back we could only dream of tracking the social network of wild bats in such great detail,” said Ripperger, a postdoctoral fellow affiliated with STRI, the Berlin Natural History Museum and the Ohio State University. “Only this novel technology would allow us to witness that individuals that groomed and fed each other in captivity also maintained their social relationships by roosting together in the wild.”

The formerly captive bats had many lasting social bonds, but not all relationships survived the transition to the tree. “Living in close contact is really important for building social relationships, but it’s not everything,” Carter said. “If you go to college, you tend to become friends with the other kids in your dorm. But after college, some of those friendships may go on but others will fade away, and that will depend on your personality and the kinds of experiences you shared.”

The Carter Lab is now assessing the bats’ personality differences and manipulating their experiences in captivity to understand how strangers become socially bonded.

Reference: Ripperger SP, Carter GG, Duda N, et al. 2019. Vampire bats that cooperate in the lab maintain their social networks in the wild. Current Biology. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2019.10.024