Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Tropical

Taxonomy

Like a cooking show with worms: Smithsonian videos teach Taxonomy of diverse Marine creatures

Text by Vanessa Crooks

At the Smithsonian’s Bocas del Toro Research Station, in Panama, marine biologist Rachel Collin runs an educational program that recruits international experts to teach and create videos about how to collect, preserve and observe marine invertebrates, passing down their very specific knowledge to aspiring taxonomists.

The program was born, in part, out of the necessity to attract researchers to the station. As Rachel Collin, marine biologist and scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), explains, her specialty is the study of marine invertebrates, animals without backbones living in marine habitats. But when she was appointed as station director, it the first time she had worked in the Caribbean.

“I went out snorkeling and I said to myself ‘wow, look at all these animals, I wonder what they are’,” Collin said. “I could recognize some, like sponges and tunicates and bryozoans, but I didn’t know exactly what they were, and there were no field guides. And the way to attract people to your research station is to tell them what you have, so that they know if there is a group they would be interested in studying, and then they’ll come and visit.”

But what is taxonomy and why is it so important? For Collin, taxonomy is an essential part of all biology.

“I always wanted to be a marine biologist, and I find evolution is intellectually engaging. As for taxonomy, I got into it because I wanted to understand the history of the evolution of life. To do that, you need to understand the relationships between species,” she says. “And when you start studying marine invertebrates, you discover new species that don’t have names. There are still so many species out there that aren’t described.”

Taxonomy, from the Greek taxis ‘arrangement’ and nomia ‘method’, is the scientific study of naming, defining and classifying groups of biological organisms within a larger system, based on shared characteristics. Although a basic taxonomy dates as far back as humankind’s ability to communicate, the first truly scientific attempt to classify organisms occurred in the 18th century, and it was mostly focused on plants used in agriculture or medicine. Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist and zoologist who formalized the binomial nomenclature, is widely regarded as the father of modern taxonomy.

“All biology research depends on identifying the organism you’re working on, and using the species name to communicate about it, so that everyone knows exactly what it is, because common names vary from region to region or from one language to another,” Collin explains. “We need something standardized so that the work is repeatable. You can’t talk about things that you can’t name.”

Collin has named 12 new species. She explains that the rules for naming taxa are not just about constructing a name for a new species, but about using the name correctly, and how the species are described and identified to be different from other organisms within the same group.

“It’s kind of fascinating, like doing historical research, because I need to check all the previous names in the group to make sure they don’t match,” she says. “So, I end up reading all this old literature from the 1800s and looking at these old paintings of shells, holding shells collected 200 years ago in my hands.”

Not only is taxonomy essential to calculate how many species there are in existence, but it is also applicable to many other scientific fields, from evolutionary biology to climate change, genetics, conservation, medicine, etc. Despite its importance, scientists rely more and more on new methods that offer ways to bypass the need to consult experts, such as DNA barcoding or metabarcoding, a technique of plant and animal identification that uses pieces of genetic code from each organism, collected in a database and available through the Internet. It’s quicker and technically more comprehensive, and it’s supposed to make identification of species less reliant on taxonomy expertise.

“They look through a database to see if the sequence matches a sequence with a species name on it. But that means someone who could actually identify it correctly had to sequence it previously and put that information into the database,” Collin points out. “So, until someone does that, metabarcoding is really limited, and it doesn’t help anyone understand the biology unless you have a reference with the species name,” she adds.

There are fewer and fewer people working in taxonomy nowadays and they may feel that their work is taken for granted, Collin says.

“There is a convention that scientists who write papers on a species don’t cite the person who described the species,” Collin explains. “That’s why the field is dying down a bit, because even if you work on an organism that is well studied and it’s important and people are using it, your work isn’t cited. Citations are used to assess the importance of scientists’ research and may be the basis of tenure decisions and pay raises or future research funding. The field is underappreciated and therefore it’s underfunded, and it’s a vicious cycle.”

A shortage of taxonomic expertise was the other part of the inspiration for the Bocas ARTS program, which Collin has directed for almost 15 years. ARTS stands for Advancing Revisionary Taxonomy and Systematics: Integrative Research and Training in Tropical Taxonomy, an award given by the National Science Foundation (NSF)’s Division of Environmental Biology, which supports the educational outreach part of the program.

She paid for experts to come and explore themselves, study the species and help her build a catalog. It was, however, difficult to find experts for some of the groups. Fewer and fewer experts mean fewer students in training, and therefore fewer people interested in the field.

“There was an Israeli student, Noa Shenkar, who really wanted to work on tunicates, and there was no one in Israel who worked with them,” Collin explains. Tunicates are an extremely diverse group of marine invertebrates that have an outer cover or tunic to protect them from predators, and many of the species live attached to a hard surface on the ocean floor. “They were telling her to work on corals, but she said ‘no, I really want to do tunicates’. But who is going to help her and show her the tricks?” Collin points out. “At that point there were five tunicate experts in the world, and four of them were over the age of 70. To connect one of those experts with that one person is difficult when they’re so rare.”

Still, Collin managed to contact a few. Once at the research station, two of the experts suggested that Bocas del Toro would be a great place to offer courses; the diversity was there, and they had dormitories and a lab with all the equipment. Also, because the coast is shallow, scientists can collect samples by snorkeling, no scuba diving license needed. Bocas became the place where aspiring taxonomists and experts can commune and share their passion for studying groups of marine invertebrates.

With the NSF grant, Collin could fund six courses in total: two courses a year, with each course lasting two weeks. But before receiving the grant, the program began with whatever funding they could find to help pay for the travel expenses for students who couldn’t afford it, and the experts donated their time to teach.

The effort paid off, and the courses were a success. “Some of them we’ve done multiple times, like the sponge class, which is super popular,” Collin says. “For the first tunicate class, Noa Shenkar, the Israeli student, came and took the course, and she is now a professor in Israel with a tunicate lab, with her own tunicate students, and she sent them to the most recent tunicate class we had. I like to think the course helped her. She was so set on wanting to study tunicates, that I think she would have found a way anyway, but I think meeting the right people really helped her.”

“There is a real sense of community as well, since there are so few people working on any one group and everyone is scattered around the world. We did a sea anemone class a couple of years ago, and there were about nine students from nine different countries, and they were so happy; the instructor was saying how amazing it was to be in a room with nine other people who got equally excited about a bump on the tentacle of a sea anemone,” she laughs. “We do follow-up surveys, and a lot of the students stay in contact with each other for years. It really does help bring everyone together.”

The courses are open to students from all over the world, and anyone who has an interest is welcome. “If you want to learn and you can use the information, you can be a student,” Collin says.

She is aware that not everyone who wants to take the courses has the means to travel, so making a series of How To videos for each marine invertebrate group would be a way for people anywhere in the world to learn.

“I also thought they would be useful for anyone wanting to identify organisms,” Collin says, adding that people often inundate taxonomists with bad photos, videos or even samples of an animal, asking them to identify it. “It could be something really interesting or from a place where it’s difficult to go and collect, so making the courses available online can help improve people’s skills at collecting and photographing that animal, and thus making it easier to identify it,” she says.

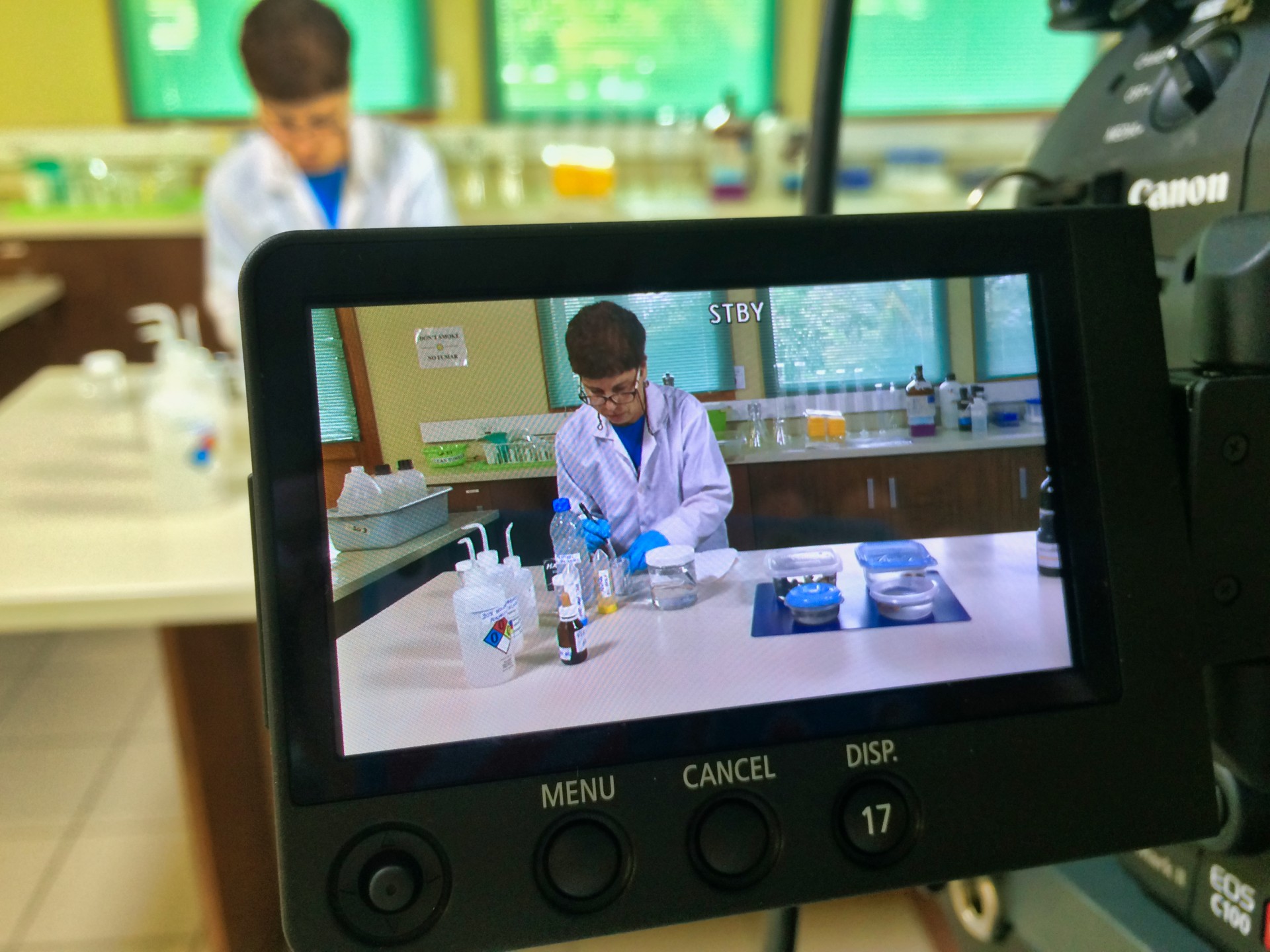

Collin spoke to STRI videographer Ana Endara and the scientists to work out the logistics for making the videos. As they were planning, Collin basically told Endara to ‘think of a cooking show’, and left it up to each scientist to know what the important aspects they should cover about their group of expertise.

They spread the videos into two trips of six to seven days, one in 2016 and the other in 2017. Each trip, Endara would work with three taxonomists, and dedicate plenty of time to work with each.

“I told them to think of their process as a cooking recipe and to be as descriptive as possible, so that anyone could replicate it with the guidance of the video,” she says.

In the field and in the lab, she would have an entire day with each scientist to go over their script and get all the footage they needed. After Endara did the editing for each video, she and the experts would review their respective videos, to check if there was anything missing or that could be improved.

“The best part was accompanying the scientists to film how they collect the organisms,” Endara shares. “I got to learn a lot. Before this, I had no idea that tunicates were animals.”

The process wasn’t without challenges. “During the first trip, when I had half of the videos recorded, I accidentally formatted my hard drive and all the material got erased. It was no joke, I felt awful. But these things happen,” Endara says. “Once I got over the panic, I talked to the scientists and we got back to work. We had to redo everything that was lost and what we still hadn’t filmed. But we did it.”

The result was an average of six videos per invertebrate group, in which the expert explains in thorough detail how to collect, preserve, dissect, examine, etc., that particular organism and why it is important, accompanied by some stunning visuals and peaceful music. The videos for each invertebrate can be found on the STRI YouTube Channel, grouped in their own video playlist.

The videos found an even broader audience than Collin expected. “I don’t think any of us thought about the people who teach invertebrate biology in university courses, that it would be useful to them too,” she explains. “After we posted them, several of my friends said they were fantastic and that they use them in the invertebrate classes, especially the tunicates one. Two of my friends said ‘we’ve never managed to dissect a tunicate before, we always try and it’s a mess, and now we have this video and we know how to do it’.”

“And now being on lockdown due to the pandemic, a lot more of those types of courses are going online and so we are getting a lot more views” she adds.

Collin hopes to continue both formats; she received a new grant, which will cover the costs of having the experts for the courses and making a video for each. However, with the ongoing pandemic, the logistics change and require a bit of creativity.

“I’m working out a strategy for the next set of videos,” Endara explains. “The initial idea was to get the scientists to do as much as they can on their own wherever they are, and I would help with editing, but not everyone can record themselves, or have the equipment or the time or the patience. So, we’ll see how it goes.”

When asked if she plans to do a course and a video herself, Collin, an expert on sea snails, is a bit hesitant. “There are already a lot of excellent resources available for people who work on snails,” she explains. “I hope to continue doing this, working on the program; there are lots of groups of marine invertebrates and lots of experts. Hopefully once these six are finished, we can do another six,” she adds.

For information about the next courses in Taxonomy Training and how to apply, visit the Bocas ARTS program website, or the website for the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.