Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Leatherback

Migrations

Leatherback sea turtle behavior: stay near home or set off across the ocean?

By Olivia Milloway

A new study finds that leatherback sea turtles tend to migrate rather than forage when chlorophyll, primary productivity, and sea surface temperature levels are lower.

Leatherback sea turtles are swimming superlatives: they are bigger, older, dive deeper, and migrate further than any other sea turtle. Researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute tagged 30 turtles and tracked their movements over three years to reveal links between environmental conditions, migration and foraging behaviors.

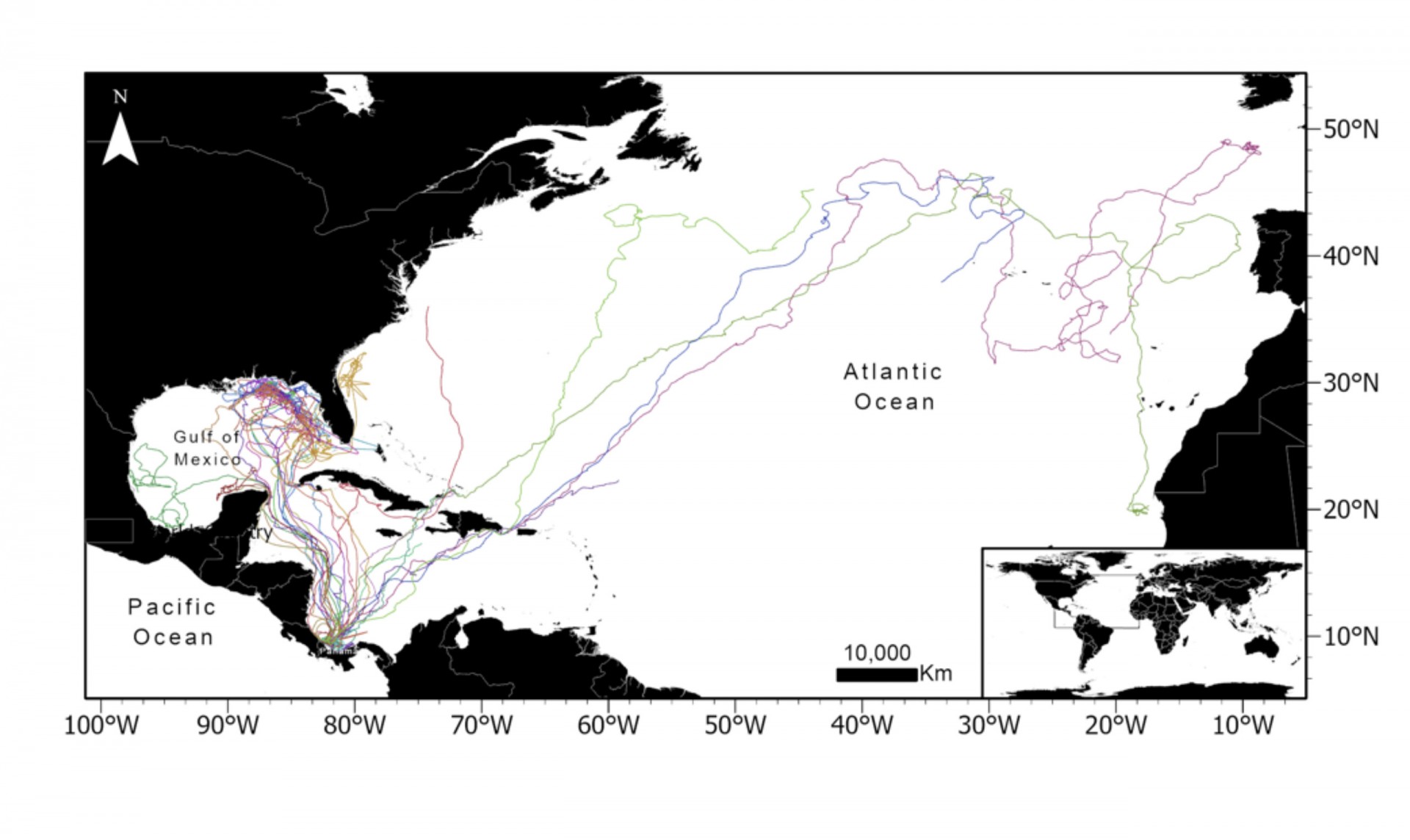

After researchers tagged the turtles at nesting grounds in Panama’s Bocas del Toro province, 55% moved northwards toward Canada and the UK, likely following seasonal prey into colder waters. The rest (45%) stayed within the Gulf of Mexico and Florida — a well-established sea turtle feeding hotspot.

The migratory routes of 30 satellite-tagged leatherback sea turtles.

Once researchers found out where the turtles spent their time, they turned their focus to how these turtles spent their time. Using existing algorithms and models comparing turtle location, speed, and direction, the team asked if the turtles were looking for food or migrating at any given moment. They discovered that the leatherbacks spent a little more than half their time foraging, (52.5%), with the remaining 47.5% of their time spent migrating.

Using environmental data from remote sensors, researchers matched each point on the migration maps with five environmental variables: chlorophyll, productivity, sea surface temperature, marine currents, and presence of eddies. They then asked whether differences in each made it more likely that leatherback turtles would change their behavior between feeding and migrating.

They discovered that the turtles tend to forage more when chlorophyll, primary productivity (basically, level of photosynthesis), and sea surface temperature were higher, while the turtles migrated more when these levels were lower. Of the five factors considered, chlorophyll was the most significant predictor of foraging behavior. Productivity was also a significant predictor of foraging behavior, but only marginally so. The presence of chlorophyll and other nutrients in the water may be an indicator that jellyfish, one of the turtles’ favorite foods, is plentiful.

“We use chlorophyll and productivity to predict potential jellyfish blooms, which are the real food for the turtles,” said Héctor Guzmán, the lead author on the study and marine biologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI).

Sea surface temperature, currents, and eddies may impact the availability of turtle food. When turtles found themselves in eddies, 69% of them decided to forage while the remainder migrated, indicating that leatherbacks likely exploit eddies to find food.

Hector Guzman applies a tag to a female loggerhead turtle after she came to the beach to nest.

Credit: Aurélie Guisnet

Rocío Estévez, coauthor on the study and fellow researcher at STRI, was surprised when the analyses did not show a significant relationship between sea surface temperature and leatherback turtle behavior. “When we discovered that sea surface temperature did not correlate with animal behavior, we reconsidered the impact of temperature on the activity of marine species and looked at other environmental factors that might be more important in shaping behavior.” However, after diving into the behavior of one specific turtle (turtle 486), they found a positive relationship between a turtle foraging and lower sea surface temperatures. “By focusing on a single animal, we discovered unique behavioral patterns that more extensive data sets might overlook, such as specific foraging strategies, habitat preferences, and responses to temporary conditions,” she noted.

Through this study, the authors saw that oceanographic factors influence the migratory paths of adult leatherback turtles migrating from Panama by either directly shaping their movement patterns or through changing the distribution of their food.

Considering climate change’s uncertain impacts on the ocean’s physical and ecological dynamics, warming global temperatures may lead to the northward expansion of leatherback turtles’ high use areas as they follow their prey to cooler waters. However, forecasting is complex and considers different physical and ecological factors.

Satellite data from this study showed these 30 turtles originating from a rookery in Bocas del Toro, Panama, passed through the exclusive economic zones of 26 countries as well as international waters. “The extensive migratory paths of these turtles, traversing international and various national waters, highlight the complexities of cross-border conservation and the necessity of sharing data and research methodologies,” the authors write.

An adult female leatherback turtle builds a nest on a beach. After nesting, she will migrate in search of food, taking her throughout the Gulf of Mexico or even as far as the United Kingdom.

Credit: UPWELL / G. Shillinger

“The life cycle of leatherback turtles is a daunting journey. They cover thousands of kilometers annually for reproduction and feeding,” emphasizes Guzmán. Leatherback turtles are listed as “Vulnerable” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) due to human-caused changes. “Our research reveals they migrate to two crucial Caribbean and northeast Atlantic areas. Their high-risk migratory behavior constantly exposes this leatherback population to danger from fishing nets, boat collisions, pollution, and, most significantly, hunting and egg poaching at the nesting site. During the tagging of these remarkable creatures, we witnessed their vulnerability as illegal activities continued to threaten them.”

The authors point to Marine Protected Areas to help reduce ongoing conflict between leatherback turtles and humans. These results highlight the “holistic approach” needed to understand the impacts of climate warming on migration paths and food availability for migratory turtles around the world.

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is part of the Smithsonian Institution. The Institute furthers the understanding of tropical nature and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems.

Guzman HM, Estévez RM (2024) Movement behavior of satellite-tagged leatherback turtles from Panama in response to chlorophyll, primary productivity, temperature, and eddy kinetic energy. Endang Species Res 55:93-107. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01362