Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Linking

the ground,

air and space

Why is NASA studying

tropical ecosystems?

By: Rosannette Quesada-Hidalgo

A NASA plane came to Panama to acquire aerial images to inform scientists about the diversity of tropical ecosystems. At the same time, researchers from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama collected similar data from the ground. The goal: to create an algorithm to better understand tropical ecosystems using satellite remote sensing in the future.

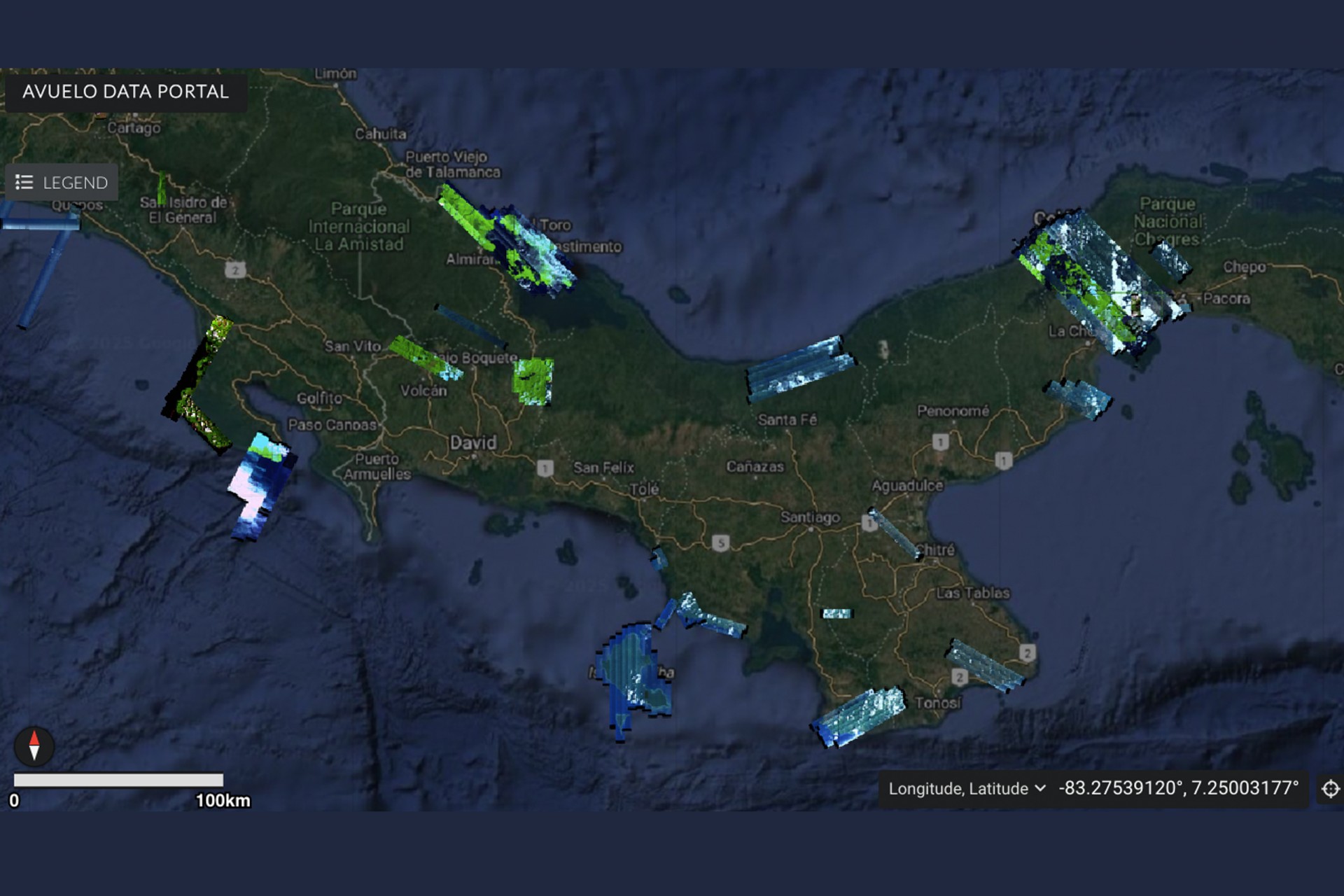

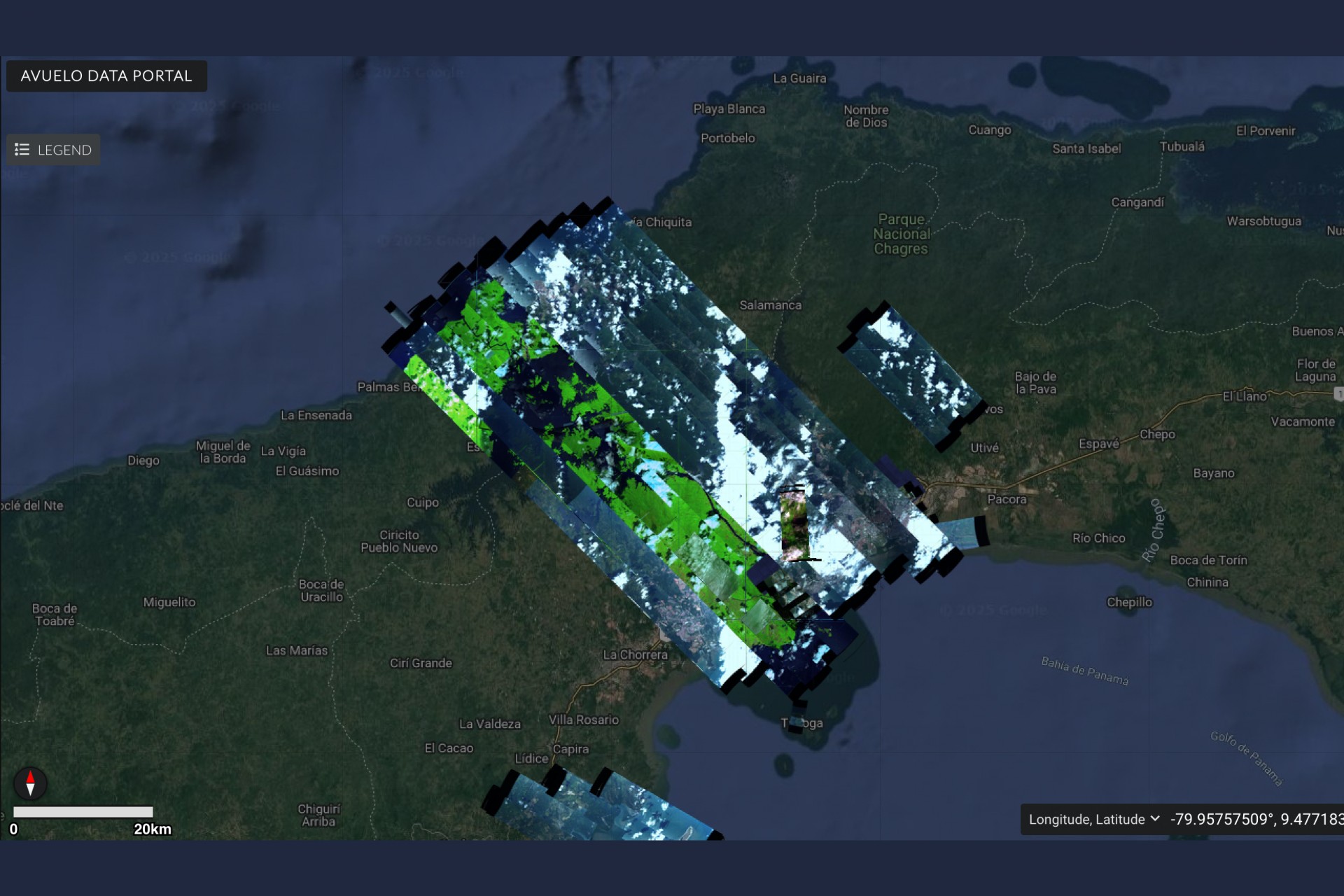

Picture this. A NASA plane flies over tropical forests and oceans, capturing pixels of colors invisible to the human eye with a specialized camera. On the ground, scientists collect leaves corresponding to these pixels, representing vegetation from a range of tropical ecosystems, including mangroves, montane forests, and dry tropical forests. In coastal areas, they collect water samples. Far above, orbiting Earth, space-based sensors offer a broad view for mapping these ecosystems. This is all part of the AVUELO (Airborne Validation Unified Experiment: Land to Ocean) project, a NASA-led campaign named cleverly after “vuelo,” the Spanish word for "flight". The campaign took place in February 2025 in Panama and Costa Rica and aimed to acquire ground and airborne data. Its mission: to understand the unique characteristics of tropical vegetation and the ocean by creating a mathematical formula, an algorithm, using real-world data collected from both the ground and the air. This algorithm will then be used by space-based sensors to enhance our understanding of tropical forests and ocean ecosystems across the world.

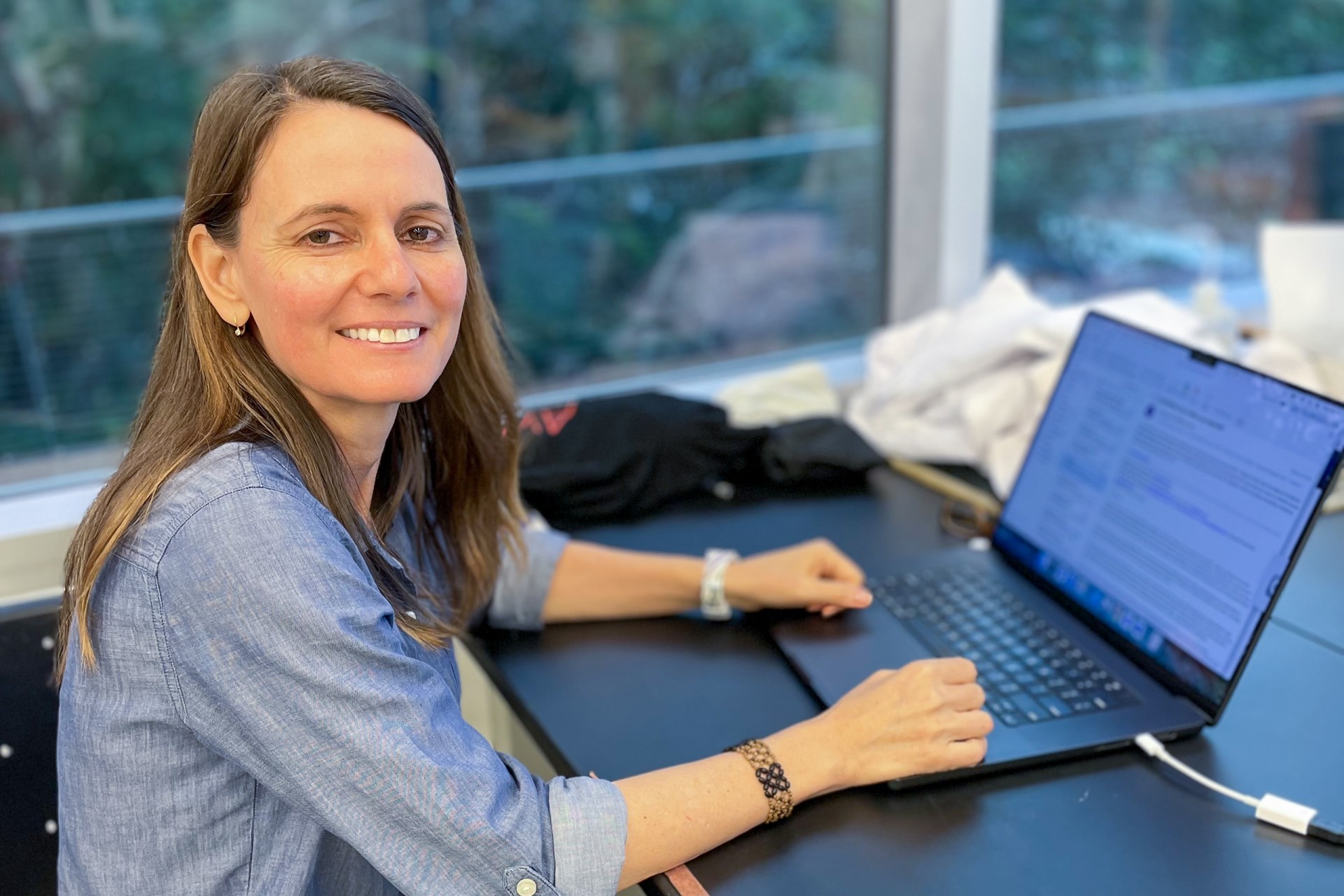

The campaign was carried out in collaboration with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and the Costa Rican Fishing Federation (FECOP), with additional contributions from various scientists and institutions. It was coordinated by the Panamanian scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Erika Podest.

Erika Podest, a Panamanian scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and coordinator of the AVUELO project in Panama.

Credit: Rosannette Quesada-Hidalgo

STRI played a pivotal role in the project, as it has been monitoring and identifying trees since 1980. This initiative has inspired 78 other sites in 29 countries worldwide, all part of the GEO-TREES project, which aims to understand the impacts of global change on forests. The fact that researchers already knew the locations and species names of the trees in these areas was essential for the project’s success. As Érika explained, “there are many maps of vegetation, but they don't really provide detailed information about their diversity, and this campaign will be key to that kind of information.” Moreover, as the STRI staff scientist and one of the leaders of the campaign at STRI, Helene Muller-Landau expressed, “Panama presents a wide variety of environmental conditions and forest types, which span almost the entire range of variation found across tropical forests globally” — making the country an ideal place to carry out this project. At the heart of the project was everyone who supported it: about 80 people, including students, interns, postdoctoral fellows, NASA pilots and engineers, and dedicated scientists from STRI, NASA, and other organizations.

Part of the team members of the AVUELO project in Panama.

Credit: Beth King

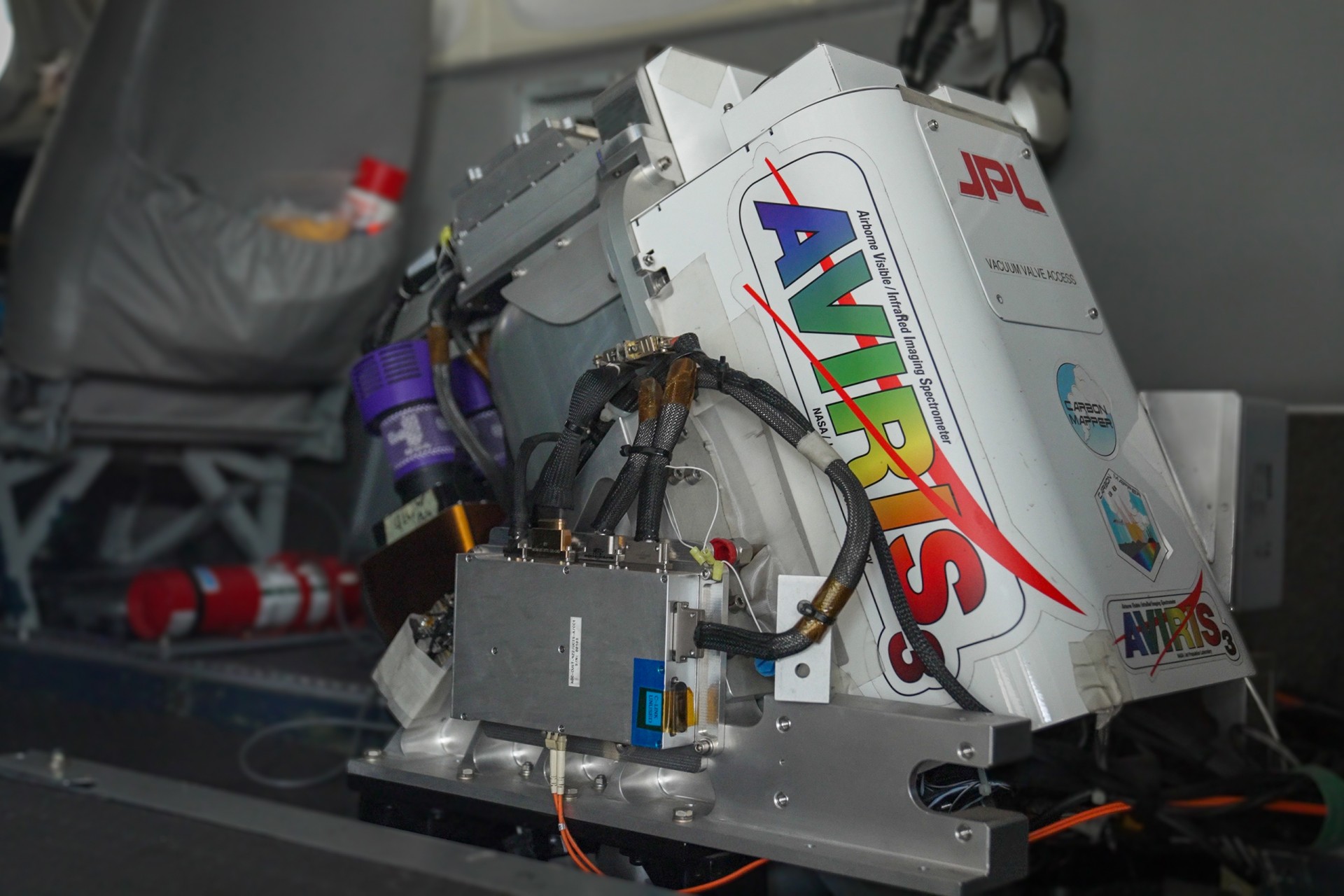

Collecting the data was no easy task. A key piece of this puzzle was the King Air N53W NASA plane, equipped with a cutting-edge instrument, a spectrometer called AVIRIS 3 (Airborne Visible InfraRed Imaging Spectrometer). As AVIRIS operator John Chapman described it, this sensor is like “a really, really fancy digital camera that can take what you would consider a green color and then break it up into 120 different kinds of green.” This spectrometer measures the radiance of a given surface — the amount of sunlight transmitted and reflected by that surface—across wavelengths far beyond the visible spectrum for humans, including UV and infrared. The results are hyperspectral images, which contain crucial data for scientists. Because different chemical substances, such as chlorophyll or methane, have a unique spectral signature — that is, like its fingerprint — this sensor can identify which chemical substances are present in each pixel of the image. Clear skies are essential for AVIRIS-3 to function effectively, and although the team faced unexpected cloudy and rainy weather during the dry season, they were able to fly and successfully capture high-quality images.

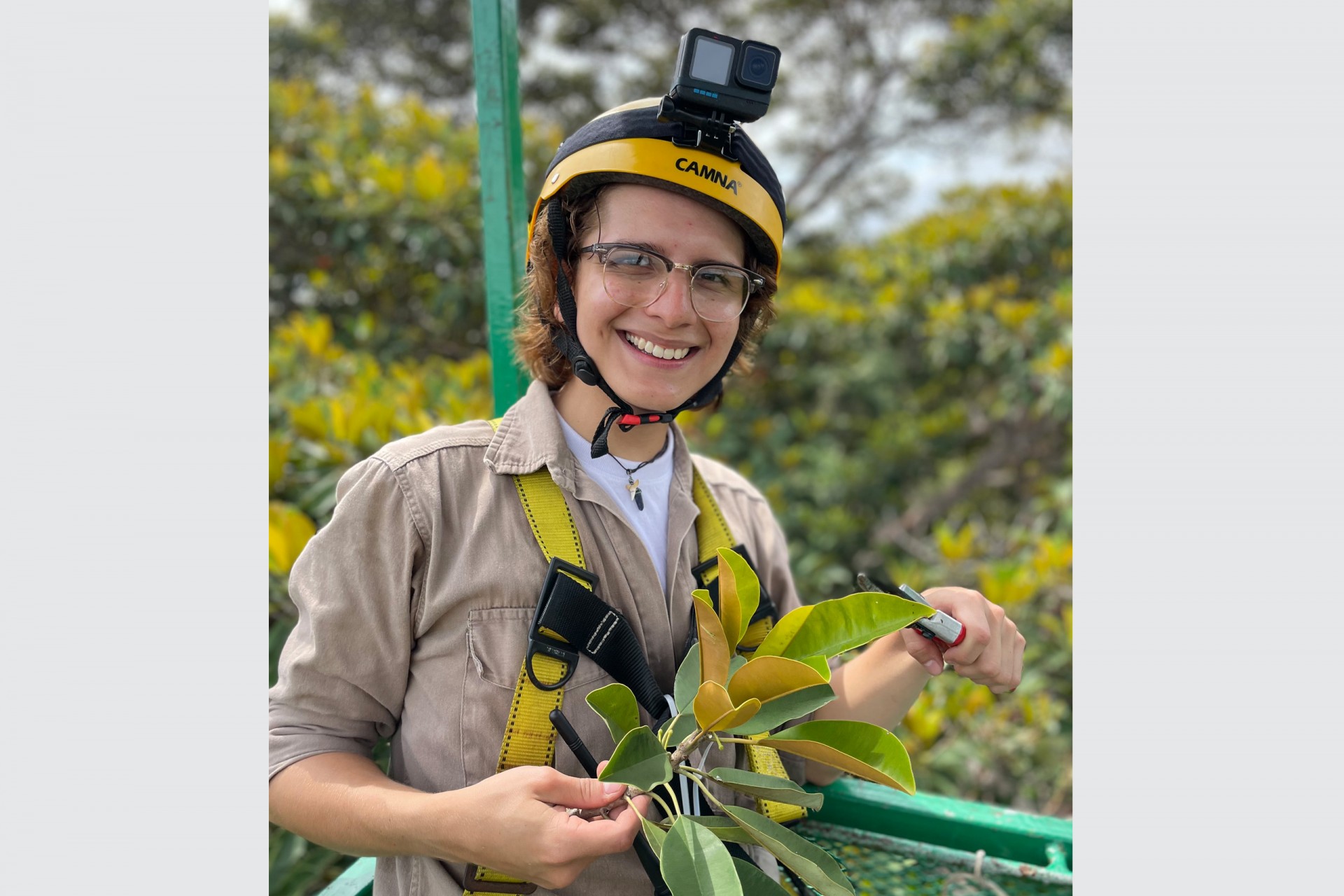

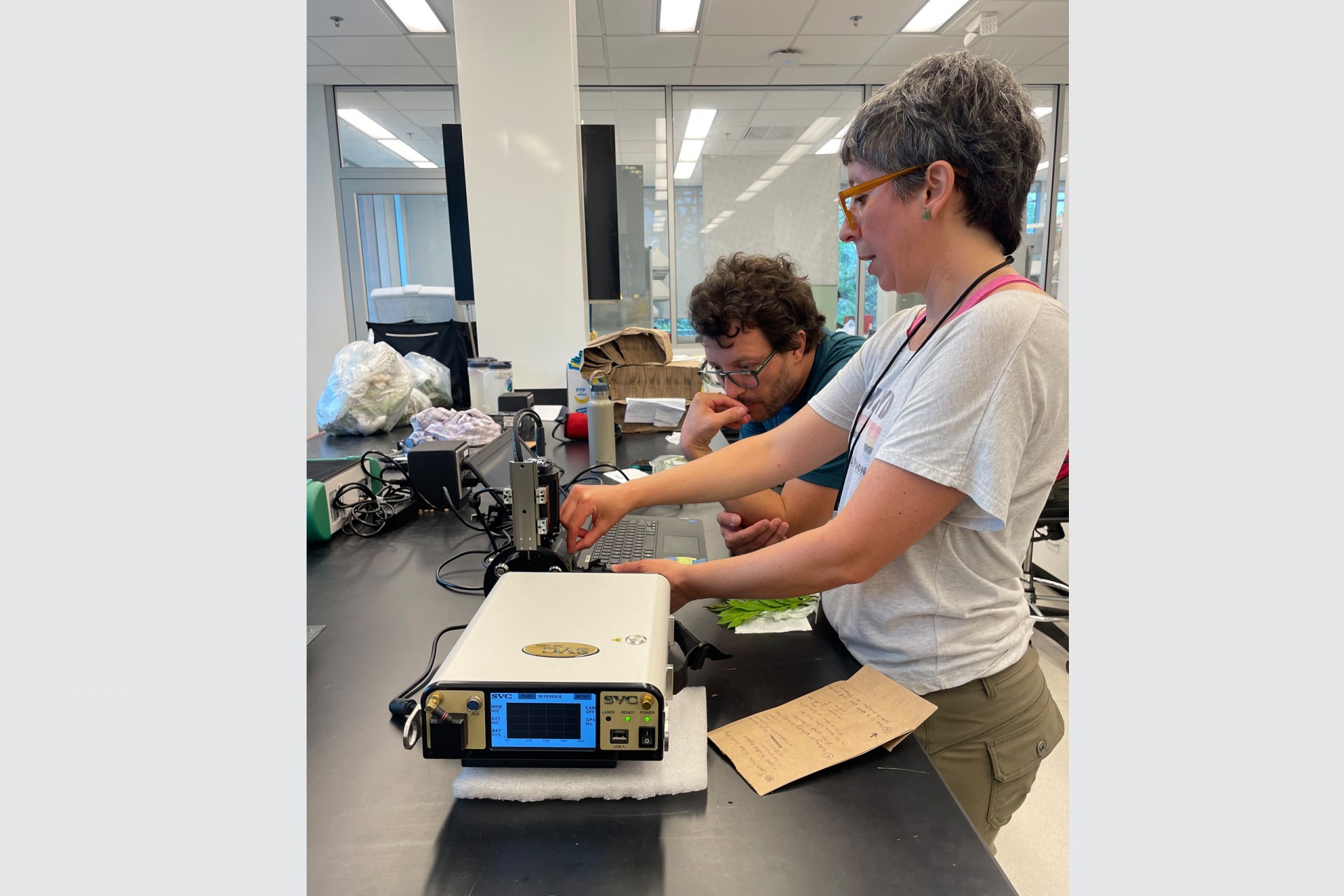

Another crucial part of the puzzle was the ground data collection. Helene Muller-Landau coordinated teams to collect canopy leaves that had been imaged by the NASA plane, bringing them back to the laboratory to measure their spectral signature. Collecting leaves from the canopy wasn't a challenge in Parque Natural Metropolitano in Panama City and San Lorenzo National Park in Colón, as STRI’s canopy cranes made it possible to reach the top of the trees. However, at other sites, different techniques were employed, such as using a long garden pruner and a special slingshot that launched a line with a chainsaw blade into the treetops. A team led by STRI scientist Rachel Collin also focused on collecting leaves from a particularly interesting ecosystem: mangroves.

During the campaign, the ground crew worked tirelessly to collect a total of 941 leaf samples from 456 plant species, spanning 307 genera and 96 families, while the plane accumulated 64 flight hours and AVIRIS collected 20 terabytes of data. Three Panamanian students had the opportunity to collect leaves on Barro Colorado Island (BCI), one of the world’s most well-studied tropical forests. The students were Paola Arosemena, a second-year biology student from the Universidad de Panamá (UP); Mara Demarsan, a forest engineering student from the Universidad Tecnólogica de Panamá (UTP); and Génesis Villareal, a biology student from the Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí (UNACHI). “Ever since I visited Barro Colorado on a school trip, I’ve always said I’d like to work here, at least once. Being able to stay here is like a dream,” said Mara.

“I met wonderful people from all areas of botany, zoology, and the NASA and STRI scientists were very attentive to us and taught us a lot. It was wonderful, and I think this experience definitely set my career on track,” Génesis Villareal, AVUELO intern.

Paola Arosemena, Génesis Villareal and Mara Demarsan, three Panamanian interns for the AVUELO project, had the opportunity to collect leaves at Barro Colorado Island (BCI) and other important field sites.

Credit: Ana Endara

Moreover, the STRI-NASA team was not only focused on collecting hyperspectral data from the air and the ground, but also aimed to study plant functional traits - leaf characteristics that reveal insights into a plant’s life strategies, such as how much a plant is investing in photosynthesis. This part of the project was led by Andrés Baresch and Natalia Quinteros, both postdoctoral fellows at NASA Goddard. Together with a large team, they collected data on various leaf traits, including leaf water content, leaf mass per area, leaf shape, leaf chemistry, and stomatal characteristics.

At the same time, two other fascinating data collections were conducted. The first, led by Yoseline Ángel, an assistant research scientist at NASA Goddard, focused on measuring the spectral data of flowers, with plans to incorporate citizen science to help monitor the phenology of tropical trees. The second effort involved photographing leaf samples to study their venation patterns, which can reveal insights into a plant’s evolutionary history. This work was carried out by paleobotanists Liliana Londoño and Laura Puente, from STRI staff scientist Carlos Jaramillo’s Lab.

NASA has been studying carbon absorption, forest quality, and mapping carbon sources and sinks in the tropics for decades, using advanced satellite technology to monitor and measure these ecosystems globally. Moreover, tropical forests are vital in stabilizing global climate by absorbing carbon dioxide and supporting biodiversity. As Helene Muller-Landau explained, “tropical forests are tremendously diverse in species composition and structure” and “satellite remote sensing data have already greatly increased our understanding of large-scale patterns of tropical forests, but extrapolating from the small sample for which we have ground data is problematic”. The results of this project, the first of its kind in the tropics, “have the potential to provide tremendous amounts of new data on geographical variation in tropical forest functional and taxonomic composition,” and will be key to designing future conservation efforts.

All data obtained during this campaign will be open-sourced and available to anyone interested worldwide.

Links of interest:

AVUELO data portal: https://popo.jpl.nasa.gov/mmgis-aviris/?mission=AVUELO

AVIRIS site: https://aviris.jpl.nasa.gov/

Quantitative Forest Ecology Laboratory: https://striresearch.si.edu/quantitative-forest-ecology/avuelo/