Leafcutter ants have blind

spots, just like truck drivers

A tropical

science legacy

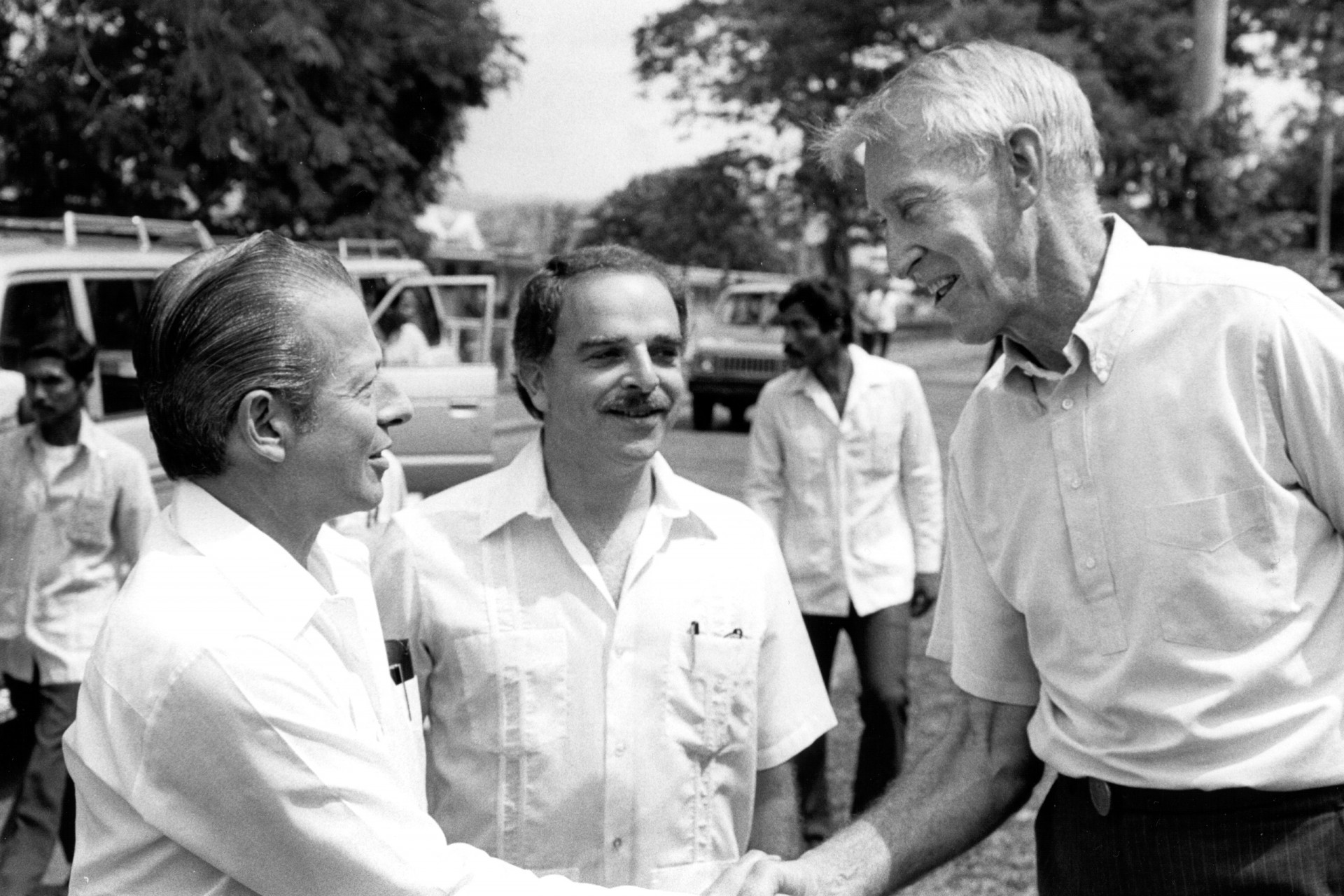

Ira Rubinoff,

Emeritus Director,

retires from STRI

Panama City

After more than 50 years at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, director emeritus Ira Rubinoff has announced his retirement. He will travel to Vienna with his wife, Anabella, who was recently designated Panama’s ambassador to Austria.

Even before his term as director from 1973 to 2008, Ira Rubinoff left a lasting positive impact on the scientific research and ecosystems of Panama and the Neotropics.

One of his early publications, in the August 1968 edition of Science, addressed the possible catastrophic consequences of building a new, sea-level Panama Canal — using nuclear explosives, no less.

Rubinoff’s paper argued that a sea-level canal would have unpredictable regional — and possibly global — impacts. The original canal, a lock system that raises boats from the Pacific to an above-sea-level freshwater lake and lowers them into the Caribbean and vice versa, is an effective barrier against most marine species invasions. Rubinoff argued that the potential for species exchange and threats to fisheries were likely to be significant and difficult to predict.

Ultimately, Rubinoff helped convince lawmakers that a sea-level canal was a bad idea.

During 35 years as the head of STRI, Rubinoff successfully guided the institute through several of its most consequential moments of the 20th century. He honed his diplomatic skills by participating in the negotiation of the 1977 Panama Canal Treaties, which transferred the Panama Canal from the United States to Panama and appointed STRI as the custodian of the Barro Colorado Nature Monument. The monument consists of Barro Colorado Island (the original Smithsonian research station in the canal) and the five surrounding mainland peninsulas.

Later, he offered scientific support for the protection of forests in the Panama Canal Watershed and the establishment of the 20,000-hectare Soberanía National Park, which buffers the canal’s eastern shoreline.

He took big gambles on research projects including the establishment of BCI’s 50-hectare plot in 1980, in which some 200,000 trees were measured and identified. Subsequent censuses in five-year intervals revolutionized understanding of tropical forest dynamics. This research set the stage for the Smithsonian Institution’s ForestGEO, a global network of 65 large, long-term forest monitoring plots that utilize the methodologies developed at the BCI plot. It also influenced the establishment of the long-term Agua Salud ecosystem-services experiment in the canal watershed.

Rubinoff supported a STRI program that uses construction cranes to study forest canopies in Panama, which also led to a global network of canopy research sites, and vastly increased STRI’s scientific reach through the addition of new staff scientists and stations around Panama. He oversaw the construction or revitalization of almost every single STRI facility.

Rubinoff deftly managed STRI’s relationship with the government of Panama. At no time was this more crucial than during the 1989 U.S. intervention in Panama.

Even though he stepped down as STRI director a decade ago, Rubinoff, a grandfather of five, remains a tireless champion for Smithsonian science in Panama. He has worked closely with donors and STRI fundraisers, mentored transitions in STRI leadership, offered generous advice to young scientists and gladly shared tales about STRI’s history with guests in his office on the sixth floor of the Tupper Center.

Rubinoff’s regular presence at STRI’s headquarters will be dearly missed by the STRI community. But have no fear, he says — he will retain his emeritus status and visit us regularly.