Marine resource use has influenced human population on the Central American Isthmus for millennia

Trapped

in time

Unearthing the prehistoric

plant species of Panama

Text by Elisabeth King

STRI Cover photo by Christian Ziegler

Little is known about the early flora of the isthmus. The first Panamanian paleobotanist aims to change this

Spanning a great abyss, the suspension bridge over the Panama Canal carries a steady stream of commuter traffic between the capital city and surrounding bedroom communities. To the south, at the Pacific mouth of the canal, lie massive port facilities and to the north, the waterway snakes through the Culebra cut…arduously excavated through the sticky red clay soils of the low continental divide.

As Oris Rodriguez crosses the bridge, the low, conical hills in the distance mysteriously transform into smoking volcanoes as she imagines a day millions of years ago when a violent explosion sent a searing cloud of ash rumbling down the valley, burning the forest in its path. Rodriguez spent days on her knees excavating fossilized trees in the area under the bridge, and her discoveries earned her a doctorate in paleontology at Royal Holloway, University of London with a grant from the National Secretariat for Science, Technology and Innovation (SENACYT).

“Since I was a child, and I watched natural history television shows (including the ones about dinosaurs), I’ve been incredibly curious about the past.”

Rodriguez majored in botany at the University of Panama, and then did a stint as a field assistant for intrepid botanist Alicia Ibañez as she described the flora of Coiba Island, but when she applied to the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM) it was to do a Master’s degree studying 50 million-year-old fossil leaves.

What is a fossil? Technically, fossils include any remains of an organism from the past—even animal tracks, plant parts and bones trapped in the ground. Most of the fossils Oris studies are called permineralizations, that occur when mineral deposits eventually substitute for plant material.

“There has been so little paleobotany done in Panama, that as the first Panamanian I felt compelled to find out more about our ancient flora.” It was actually perfect timing because the Panama Canal expansion was a major opportunity for geologists and paleontologists as huge, earth-moving equipment opened up huge new areas for their exploration.

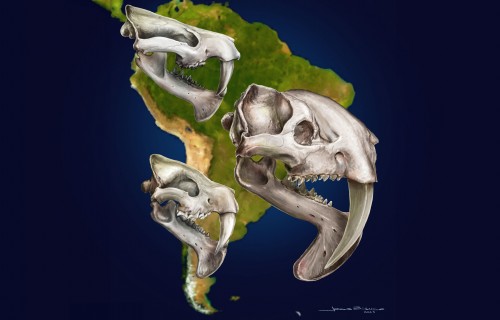

Joining a team organized by STRI paleontologist Carlos Jaramillo, Oris began to work near the bridge in a ~19 million-year-old area called the Cucaracha Formation. There, she discovered a new species in the Malvaceae family that later became extinct and the first record of a plant like Prioria (related to what we now call cativo) in the bean family (Leguminosae). Also, she found a plant in the order Malpighiales with a particular combination of characteristics that extends our knowledge of this order to the Neotropics. Some of her findings indicate that there may have been exchanges of trees between North and South America even before the landbridge that later formed to join the continents was even formed.

And then there are the ominous carbonized stumps that are evidence of a violent volcanic eruption.

“Panama fascinates me. There is still so little information, it’s like a canvas waiting for its history to be painted in,” says Oris.

Her newest focus is the Azuero peninsula. Since an article written in 1970, no paleontology has been done there until three years ago. Working near Ocu, mostly on private farms in cattle pastures, she has unearthed huge trees up to 20 meters long and a meter across, which may be a new species in the same family as mango trees.

Miguel Martinez, an undergrad from the Centro Universitario de Herrera in Chitre has been working with her. Recently, they found a mysterious plant fossil. The only similar plant that has similar characteristics today is from Indo Malaysia and Africa.

The beautiful, colorful fossilized wood on Azuero is often found by collectors and ends up being removed and sold. “With the University of Panama, we are working to create a proper repository where we can store and catalog samples.”

“We really don’t know the age of these wood samples. We think it may be around 30 million years old. But we’re working on a couple of analysis, like using zircons, the tiny crystals in the rocks, to date them,” says Rodriguez. “One of the big challenges is that Panama doesn’t have an updated geological map with the proper resolution we need. No one has made a new map since the 1970’s. This makes it really difficult to tell how old the fossils are, because you have no detailed information about their context.”

Rodriguez hopes to play a role in making that map: “I love to help tell this story.”