A guiding

force in

archaeology

Wishing farewell to our friend, Dr. Richard Cooke

He would have turned 77 this past October. We deeply miss his endless enthusiasm for learning and his passion for teaching others.

On February 23, 2023, the STRI Archaeology Laboratories, STRI and Panama lost a longtime friend and leader, Dr. Richard Cooke.

No words can express how much we miss Richard’s endless enthusiasm for learning and his passion for teaching others at every opportunity.

He was the guiding force in our labs for many, many years and has long been a significant investigator of the archaeology of Panama and the southern isthmus.

Richard Cooke was born October 28, 1946, in Guildford, England, and often recounted developing a lifelong interest in observing wildlife— specifically birds—at a very young age.

Richard spent his early years studying a number of topics (and languages) until he settled on archaeology, obtaining his undergraduate degree in Humanities from the University of Bristol in 1968.

He became interested in the pre-Columbian history of Panama fairly early during his graduate studies under the mentorship of archaeologist Warwick Bray at the University College London.

After spending two field seasons conducting excavations and surveys in central Panama, he obtained his doctorate in 1972 with a dissertation on the ceramics of Sitio Sierra and other sites in the general Coclé region, titled The Archaeology of the Western Coclé Province of Panama.

Richard returned to Panama after that, accepting various contract excavation assignments for the Panama government and international researchers. These included excavations in Panama’s historic “old quarter,” or Casco Viejo, and accompanying archaeologist Junius Bird (American Museum of Natural History) in deep pit excavations at the site of Cueva de los Ladrones in Coclé province. Richard would recount these expeditions later with some amusement, including the time Bird had him excavate many meters of bedrock in a desperate attempt to find Paleoindian evidence.

Richard left behind an important collection from his archaeological excavations in Panama, including ceramics, lithics, shells, artifacts, and organic material (such as human bones, faunal bones and plant remains).

Credit: Sean Mattson, STRI

During these years, Richard benefited from research facilities and close collaborations at STRI, receiving a one-year STRI Postdoctoral Fellowship in 1974 to expand his previous excavations at Sitio Sierra and maintaining a STRI Research Associate status after that (1975–1983).

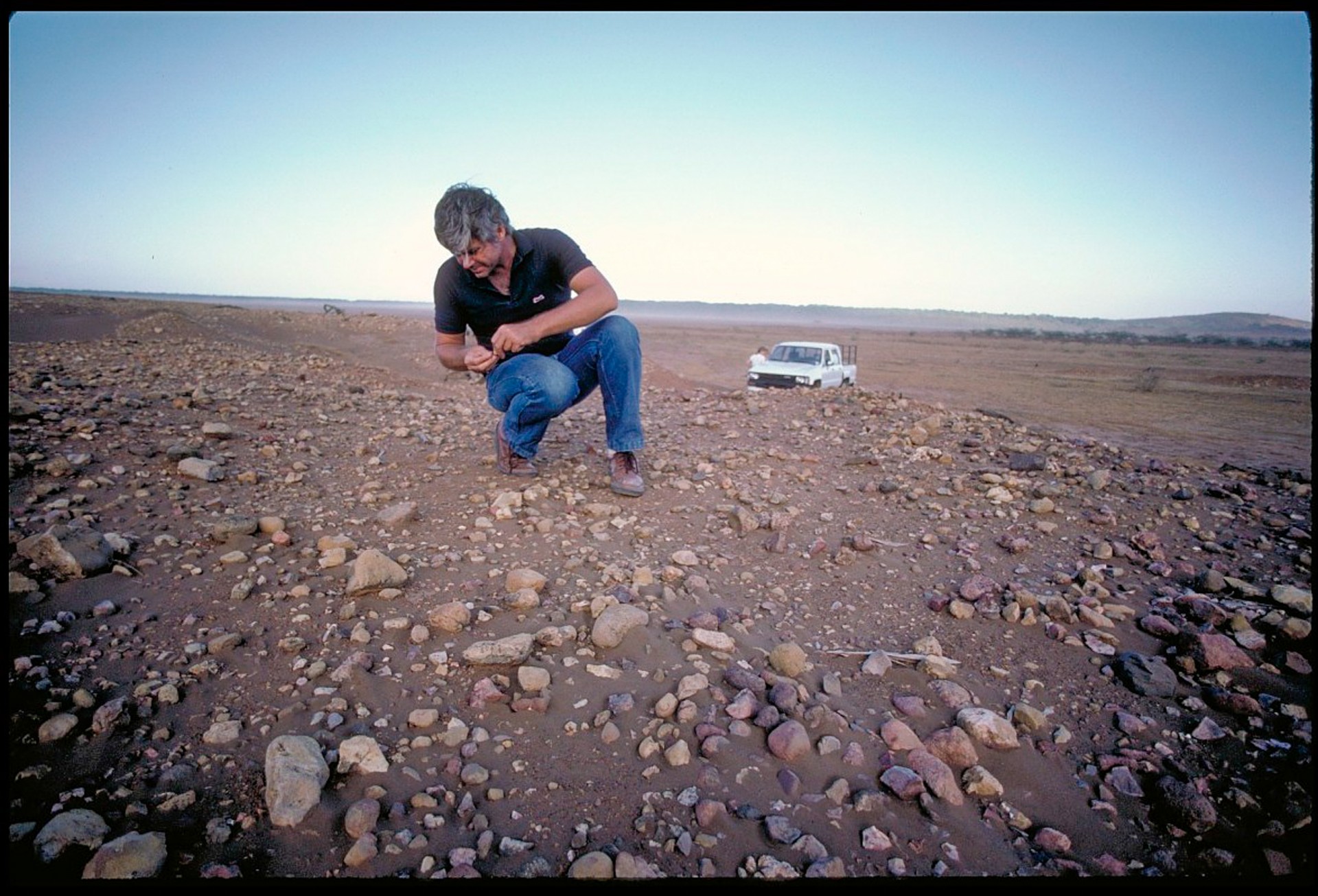

In the early 1980s, Richard joined Anthony Ranere and Olga Linares on an NSF-funded multi-year survey of the Santa María River and its surroundings. One of the goals of this expedition was to locate sites in relation to one another across the landscape, as well as locate sites with preceramic occupation – the equivalent of finding a needle in a haystack.

The project identified nearly 600 new sites, at least 100 of which had preceramic evidence. Richard and the team excavated several, which provided a springboard for subsequent generations of new projects in central Panama.

STRI officially hired Richard as a staff scientist in 1983. He spent the next decade developing an extensive program of study for local and international researchers.

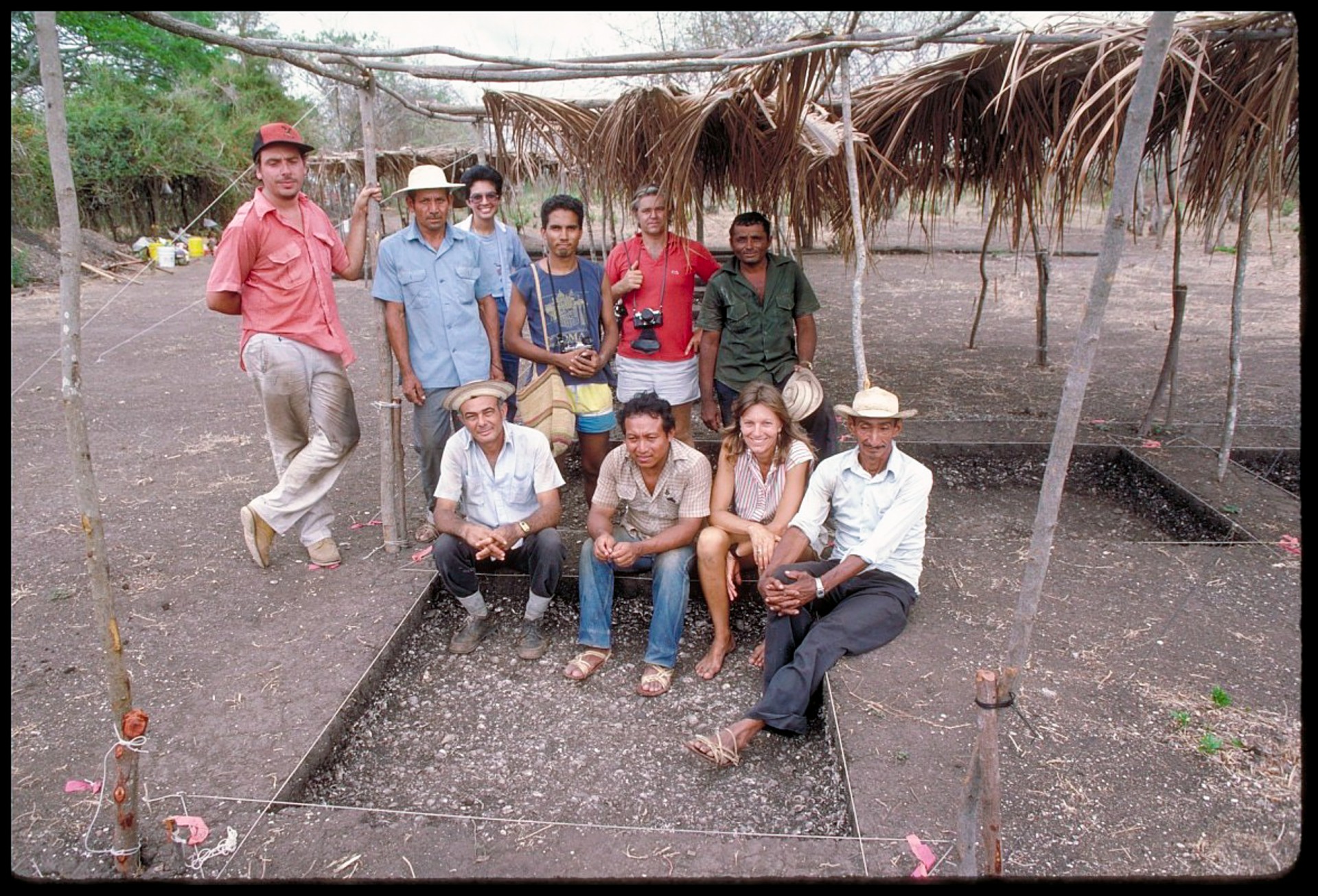

Aguadulce Shelter site. Richard ‘Spud’ McCarty, Cathy Shelton, Olga Linares, Richard Cooke and Tony Ranere

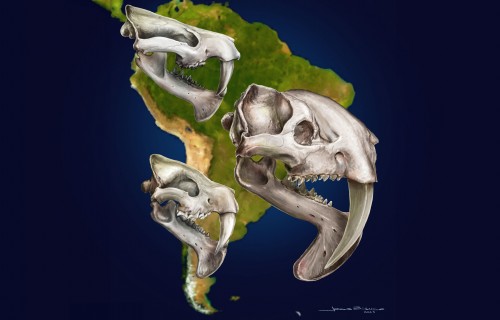

Although his dissertation focused on ceramics, Richard simultaneously developed a passion for identifying various wildlife. He slowly built up a comparative skeletal collection of fauna to assist in the identification of archaeological remains. An anecdote from Warwick Bray from a Colombian field expedition in 1970 recounts:

“He [Richard] had just started to be interested in creatures, alive and dead, and was beginning to put together his reference collection in Panama. We were living in a ramshackle hotel in a little pueblo, and every night, after the owner had gone to bed, Richard would take over the kitchen and boil down small birds or animals. The smell was terrible, the hotel complained and threatened to throw us out, but, as the only clients, we were in quite a strong position. We started off with roadkill, then told the small boys of the pueblo that they could earn a few pesos by bringing in dead animals. No problems with lizards, fish, and small mammals, but one day a kid turned up with a sack that wriggled and writhed. He tipped out a large anteater, very angry and waving a wicked set of claws. Richard looked at me and said, ‘We can’t kill this, can we?’ So we bought it, put it back in its sack, then crept out to release it on the edge of town.”

Anyone who knew Richard will remember his uncanny ability to remember the scientific name and facts of nearly every vertebrate species in Panama, usually accompanied by personal (and often humorous) anecdotes about his observations of each animal’s unique behavioral quirks. He had a particular love of catfish and was the namesake of a new species identified in the Gulf of Panama: the Notarius cookei.

In the 1990s, Richard began excavations at the enormous 150 ha site, Cerro Juan Díaz—an immensely complex site that took ten years to excavate and the rest of his career to analyze and develop into a series of fascinating publications in Spanish and English.

The Cerro Juan Díaz Project started as a rescue operation of a looted pre-Columbian village that spanned c. 200 BCE until shortly after the Spanish arrival. Research at the site involved a team of experts and students. Among the latter included several young researchers who continued to industrious careers as archaeologists and conservators, including Luis Sánchez Herrera, Ilean Isaza Aizpurúa, Diana Carvajal Contreras, Julia Mayo Torné, Claudia Díaz, Máximo Jiménez, Tomás Mendizábal, and many more. Analyses of the material recovered at the site are still ongoing.

In the early 2000s, Richard assisted with the excavations and analysis of the Vampiros rock shelters with archaeologist Georges Pearson, finding early evidence of human tool manufacture on the isthmus. In 2007, he moved to another large project on the Pearl Island of Pedro González in the Gulf of Panama.

Through analysis of the Vampiros rock shelter, Richard found early evidence of human tool manufacture on the isthmus.

Credit: Marcos Guerra, STRI

While surveying one of the beaches set for resort construction, an extensive multi-layer midden was uncovered, at the bottom of which was a layer of dense bone and shell refuse dated to 6000 BP.

Archaeologist Juan Guillermo Martín and others continued excavations at Pedro González with Richard’s assistance until 2015. They have continued to publish remarkable findings of this early deposit, revealing surprising information about an island ecosystem that no longer exists today.

Somehow, between excavations and writing, Richard engaged in many personal pursuits and hobbies. He was an avid birdwatcher and fond of examining the various methods of artisanal fish capture along the coast.

He was a particular connoisseur of various sports in Panama, Britain, and elsewhere, and it was not uncommon to hear quips about the latest match during a conversation.

He was an excellent public speaker and loved engaging with school groups and at public events around Panama. For many of us, he was a mentor, dear friend, and source of fascinating facts about Panama’s ancient and recent history, somehow finding the time to maintain correspondence with anyone and everyone asking about Panama’s past.

Richard earned several awards during his life, many of which he accepted quite humbly, in keeping with his personality. These included the Orden de Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 2006 from the Republic of Panama, International Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2013, Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) in 2018, and the International Council for Archaeozoology’s Committee of Honor in 2020.

In October of 2023, the XIV Congreso Centroamericano de Antropología was celebrated at the Universidad de Panamá in his honor, together with Reina Torres de Araúz. The session in Richard’s honor was an illustrious parade of friends, colleagues and disciples dissertating on all the themes of Panamanian ancient history of which he was a pioneer. Rarely would you have met such an erudite, respected and renowned scientist with a humble, approachable and friendly disposition towards all.

Those who will miss Richard the most are his beloved children, Ana, Juana, Ian, and his grandson Adrián, whom we thank for having shared Richard with us all this time.

Richard had a genuine love of life and learning, one that was infectious to all who knew him. We will miss him greatly.