Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Superheroes

The avengers

of the forest

Barro Colorado Island

Discreet and alert, park rangers spend 24 hours a day, 365 days a year on the lookout for threats to the forest and animals of Barro Colorado Nature Monument

It’s mid-April and Mario Santamaria steers a black boat through the channel behind Barro Colorado Island, the side that visitors to the research station of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute usually don’t see. Except for a narrow passageway for small boats, this area of Gatun Lake is a meadow of tree trunks protruding from the water, remnants of the forest flooded to create the Panama Canal.

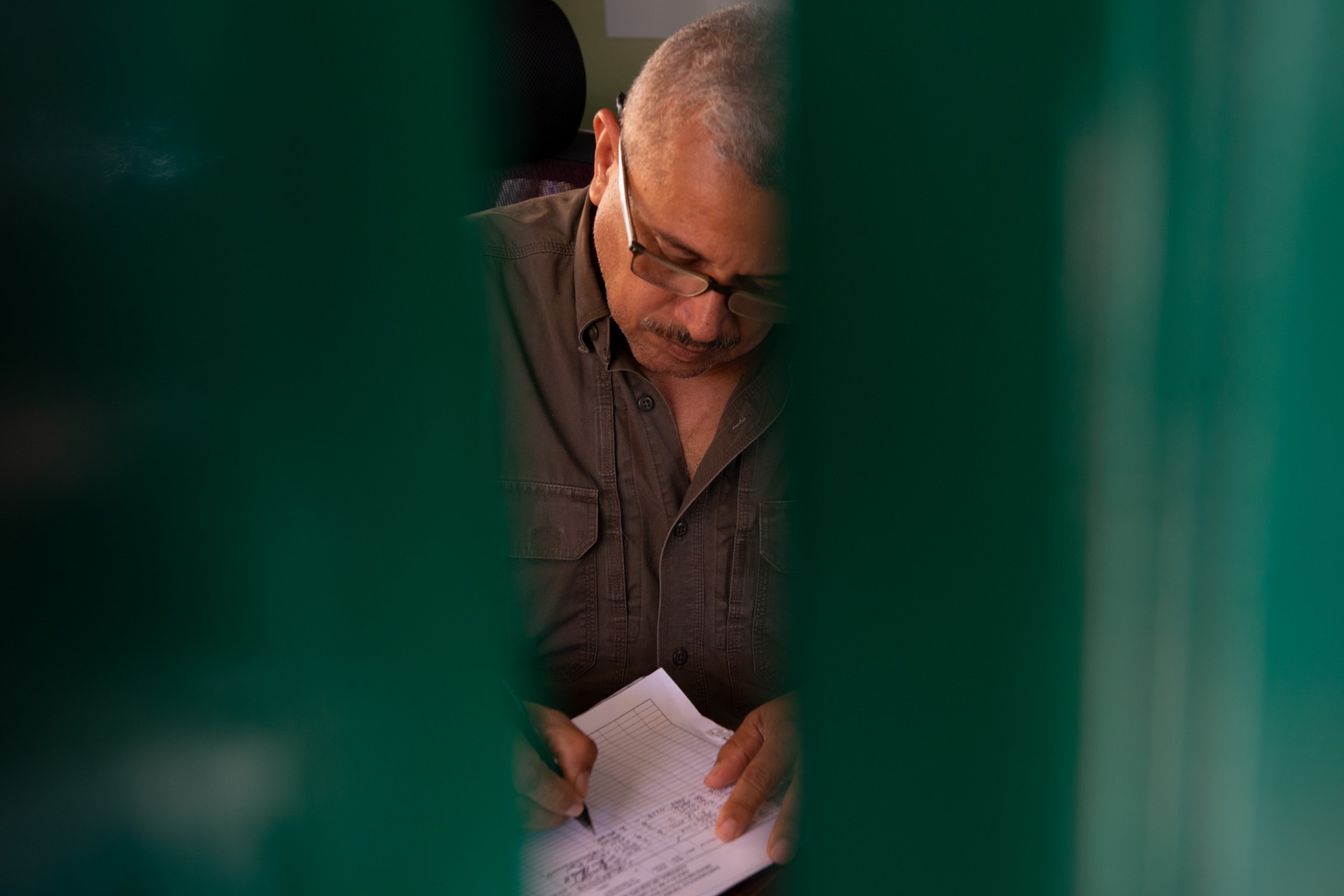

Mario supervises the 17 park rangers who guard the Barro Colorado Nature Monument, a protected area since 1977, which includes the island and five neighboring peninsulas. If not for the park guards, who have been clearing trunks since the 1990’s, diving underwater to saw them off, scientists would not have easy access to the surrounding islands and peninsulas.

Mario cuts the speed of the motor. Lake levels are very low at the end of the dry season, to the point that some of the cut trunks are very close to the surface. From time to time, the bottom of the boat scrapes one.

Dressed in camouflage, with metal-soled boots to protect their feet from thorns and a backpack equipped for forest survival, two park rangers and a Panama police officer descend on the Bohío Norte peninsula to do their rounds. Every shift includes a team like this.

They walk the trails of the Nature Monument and clear them of fallen trees. They also maintain fences that demarcate the protected area. But their main task is to search for signs of hunters, by walking off-trail through the forest.

The hunters are cautious, but the rangers have a keen sense of smell, especially the cohort that started three decades ago, alongside Mario. The majority were young men from the countryside, some trained as biologists. Without much formal supervision and based on their own experiences, they gradually built today’s forest conservation program.

“I'm from Soná in Veraguas. My dad was a hunter and a farmer: he had guns and dogs. I learned about different types of hunting and to recognize animal tracks,” Mario reminisces. Then he points to a nearby tree, with the bark cut off on both sides of the trunk. There are also some bent branches in the vicinity. These are tricks hunters use to navigate at night. Additional evidence includes fresh footprints, spent ammunition and food debris. They pay special attention to water sources and fruit-bearing trees: places that attract animals.

When they find evidence, the park rangers may stake out an area for a few days. They pick a place near the path of the hunters and build a campsite, where they remain alert and silent throughout the night.

For many, this is the most challenging aspect of the job: to simply wait quietly in the dark. Because the nocturnal forest is often silent, any sound, however insignificant, can be perceived in the distance. Even odd smells, like insect repellent or fabric softener, may alert the hunters.

Most hunters enter the peninsulas because they share a border with mainland populations in Colon and Panama provinces. To maintain a good relationship with nearby residents and educate them about their work in the Nature Monument, park rangers organize sports and cultural activities, as well as health fairs. They would like to discourage hunting through education, and also to gain people’s trust, in exchange for valuable information.

Hunting has significantly decreased since the 1980s, but as recently as April this year, they caught two groups of hunters and turned them in to the authorities. Both carried weapons. One carried a peccary, a coveted prey. The laws that punish illegal hunting have also improved. Before, it was considered a misdemeanor, and the profits from selling hunted meat were higher than the fines. Now it is a crime that can lead to years of imprisonment or a more significant fine.

For Mario, it is almost a violation of his personal space. “When hunters enter the forest, I feel like they are invading my home,” says Mario. And although it angers him and he often has to chase them down or handle situations in which the hunters could react violently, he still talks to them compassionately, hoping to raise awareness. In the end, the objective is not to punish just for the sake of it, but to protect nature in the long run.

For the park rangers, their main motivation for facing hunters and inclement weather, spending sleepless nights, sacrificing holidays and exposing themselves to disease-transmitting species is their love for the flora and fauna of Barro Colorado and the peace that the natural world offers.

“The survival of human beings depends on nature and protecting it is a noble task”, says veteran park ranger Gabriel Abrego, during the night shift, as he takes a deep breath to fill his lungs. “Besides, where else could you find air as pure as it is here?”