Smithsonian science helps understand blue whale migratory and foraging patterns to inform conservation strategies

STRILights

Learning from Tropical

Nature in 2018

World’s tropics

Join us to celebrate a few of the discoveries made in 2018.

STRILights Annual Report

Nature—a wise old teacher—has solved problems posed by the environment for billions of years. As we face daunting challenges such as human overpopulation and migration, food security and changing climates, we look to the world’s most complex natural systems—tropical forests and reefs—for new knowledge to inform our evidence-based decisions.

Join us to celebrate a few of the discoveries made in 2018.

When we look back in time…

We discover that many organisms, not just humans, take longer to adjust to new ways of doing things. For example, a study of fossil marine invertebrates adapted to change in the Caribbean environment after the Panamanian isthmus rose found that younger species took advantage of new opportunities more readily than older species.

STRI paleontologists dramatically illustrated the prehistory of Colombia in Hace Tiempo, a book made available free to all Colombians in public schools so that they can learn about Titanoboa, the world’s biggest snake, and other equally fascinating species discovered there.

From human history…

Our archaeologists learned that Mayas traded dogs for ceremonial use, bringing them from the highlands in Guatemala to lowland ceremonial centers where they were offered as sacrifices.

In Panama, STRI scientists discovered that archaeologists working here in the 1950’s exaggerated reports of violent deaths among native peoples, perhaps contributing to a tradition of portraying them as savages to justify their domination by colonial cultures.

How do animals cope with environmental change?

Using camera traps in Coiba National Park, STRI scientists captured the first-ever evidence of white-faced capuchin monkeys using stone tools to break open seeds for food on Jicarón island. Because these particular monkeys live in a place with no natural predators, it is thought they came down to the ground and eventually learned how to use these tools.

However, the same monkeys on a nearby island have not learned how to use stone tools. In addition to witnessing evolution occur in real-time, this discovery may help shed light on how prehistoric humans evolved to learn how to use tools.

In addition to witnessing evolution occur in real-time, this discovery may help shed light on how prehistoric humans evolved to learn how to use tools. Will human innovation explode in the absence of warfare and other immanent threats?

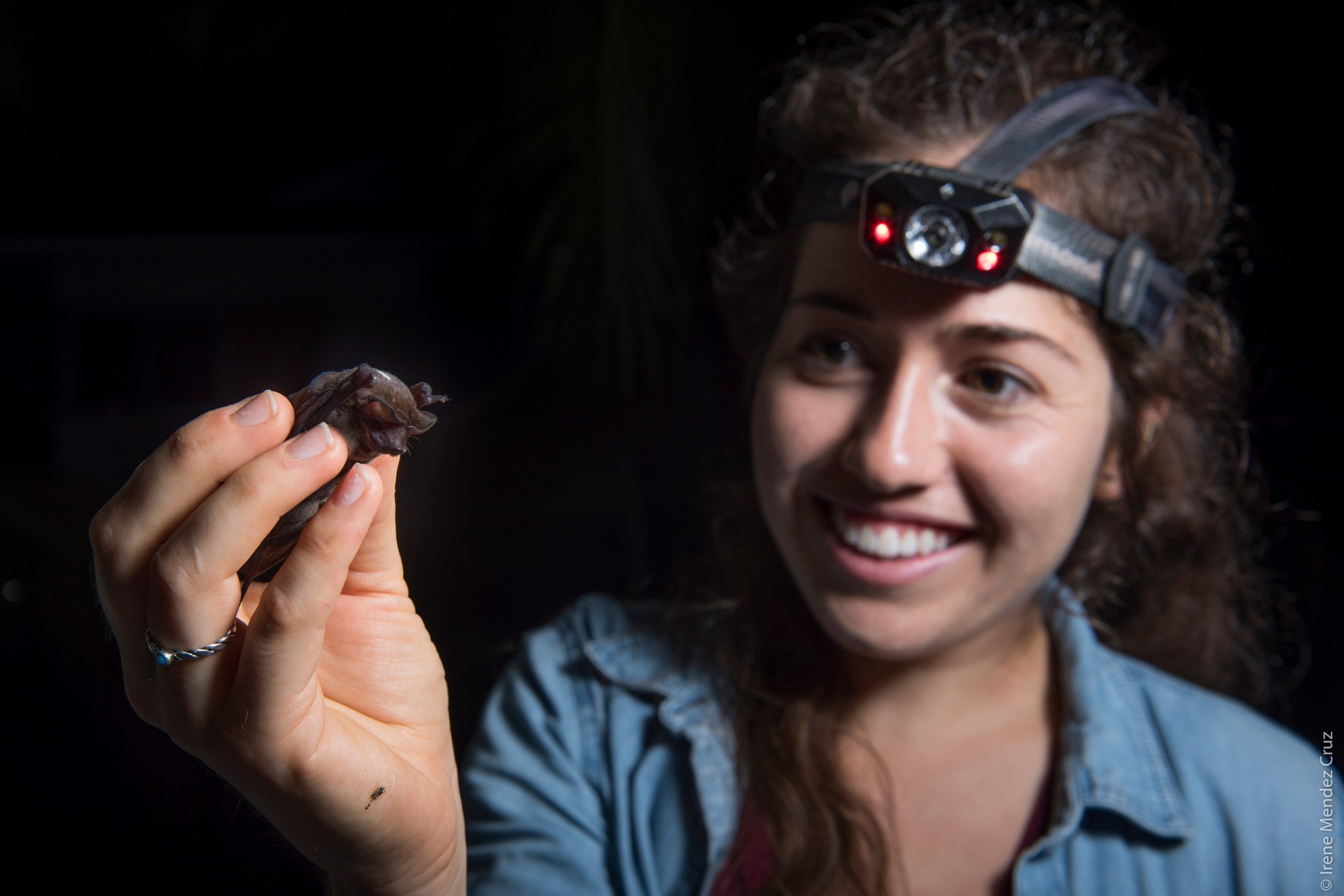

Fringed-lipped bats (Trachops cirrhosus) learned from round eared bats (Lophostoma silvicolum) to recognize a prey cue, demonstrating how species can adapt by learning to respond to totally new environmental cues. Starving vampire bats with more friends were more likely to be fed than bats with fewer friends.

Mother tent-making bats (Uroderma bilobatum), prod their voraciously hungry young pups with their forearms, perhaps encouraging them to wean and leave their mothers’ care.

Frogs are leaping back from the brink of extinction. Researchers found wild survivors of the chytrid fungal disease, indicating that some wild frog populations must be resistant to the disease and may be able to naturally repopulate areas where the epidemic wiped out the majority of their relatives. This is good news because amphibian populations everywhere are threatened by this disease, which still has no known cure. STRI successfully released captive frogs that have been inoculated against the disease in an effort to test the potential for repopulation efforts.

It pays to be a frog in the city. Male tungara frogs living in urban environments attract females by putting on “sexier” mating displays than frogs in nearby forests. With the cacophony of the urban jungle, the males have adapted these displays so that females would more attracted to the calls of urban males than their forest-dwelling brethren.

When we look underwater…

Below the range of SCUBA in Curaçao, Smithsonian deep reef explorers discovered a new world, where roughly half of the fish still have no names. They christened this dark zone the Rariphotic and named several of the new fish species sampled from their submersible.

STRI researchers and collaborators also named new coral species in Panama’s Coiba National Park. Our new Pacific research platform on Coibita Island will be an amazing jumping off point to learn more about the Tropical Eastern Pacific, including islands, reefs and underwater seamounts.

A whale-shark named Anne traveled across the Pacific from Coiba in Panama to the Marianas Trench, a total distance of 20,142 kilometers (more than 12,000 miles) according to satellite-based tracking. This is the longest whale shark migration ever recorded and the journey underscores the critical importance of the Panama Basin to the world’s marine migratory species.

To minimize lethal collisions, Costa Rica adopted new shipping routes based on our studies of whale migrations and a similar system we helped put in place at the mouth of the Panama Canal.

We learned that to combat declining fish stocks, anglers should throw back the biggest mother fish who are the best breeders, upending the conventional practice to release the “small fries”.

Read more about our marine research in the newest issue of Trópicos Magazine.

How do forests respond to global change?

Taking advantage of an especially extended El Niño drought, researchers in the Agua Salud land-use experiment revealed that the survival of young forests depended mostly on their ability to access water in the soil whereas older forests were affected more by the quantity of water they lost to the atmosphere through their leaves.

Based on data from forests in 21 countries, all part of STRI’s ForestGEO network, researchers predict that the largest one percent of trees in older forests represent 50 percent of forest biomass worldwide and store half of the world’s forest carbon. The biggest trees not only provide habitat for animals, they strongly influence the forest around them, another reason to advocate their conservation.

Panama is at the forefront of tropical reforestation and restoration, building on nearly one hundred years of tropical forest research. From soil to satellite mapping, hands on measurements of trees and animal camera trapping, sites like Barro Colorado Island and the Agua Salud river basin within the Panama Canal Watershed are some of the best-described tropical forests anywhere. New technology, such as drones mounted with cameras and sensors, add to our ability to closely monitor forest health during severe climate events like the two-year-long El Niño drought Panama recently experienced.

Thank you to everyone who cares about tropical environments and who makes our discoveries possible: our host countries, especially Panama; our generous donors; our scientists, visitors and students; our administrators and support staff and all friends of tropical nature.