Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Picky

eater

Invasive lionfish may

be a selective predator

Curazao

By evaluating the diet choices of this species in a semi-natural environment, scientists could improve predictions of how it might affect newly invaded communities

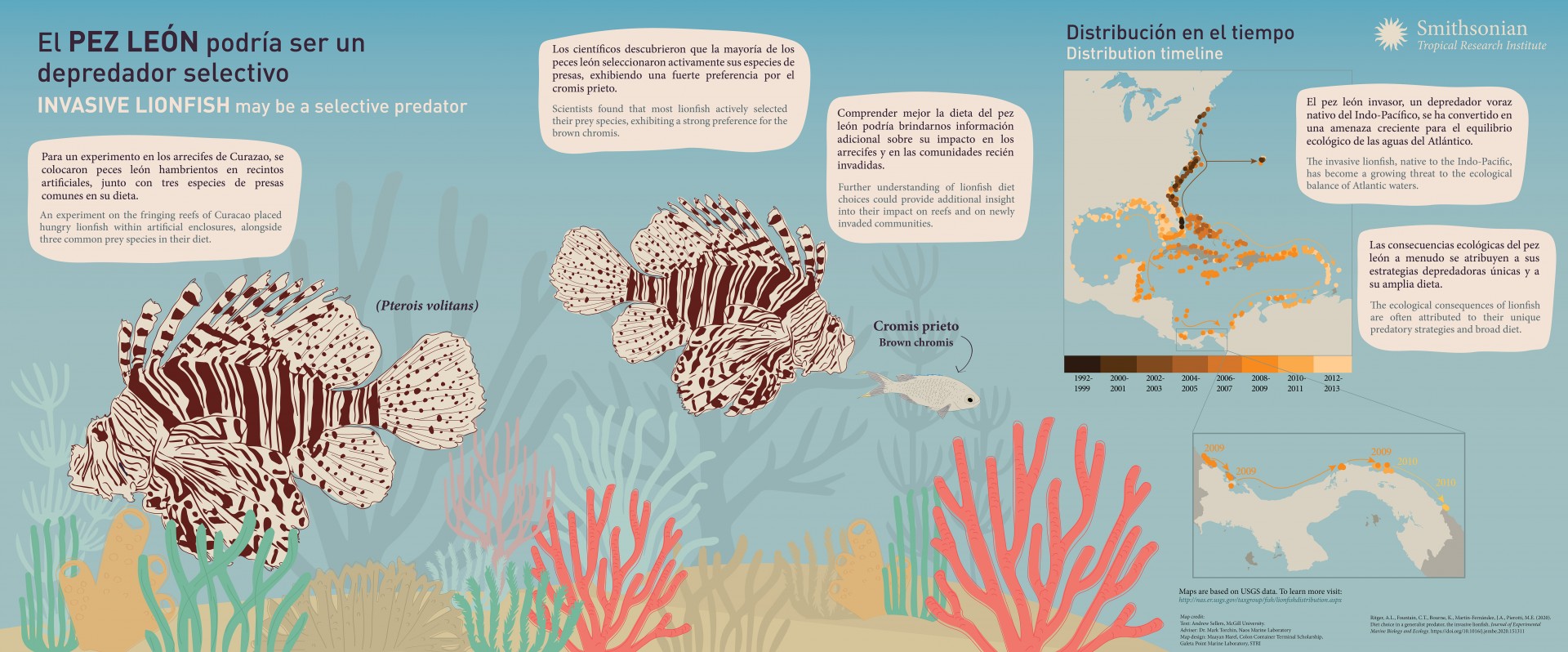

Invasive predators have the capacity to dramatically alter marine ecosystems. The lionfish, a voracious predator native to the Indo-Pacific and now established along the southeast coast of the U.S., the Caribbean and parts of the Gulf of Mexico, has become a growing threat to the ecological balance of Atlantic waters. To gather insight regarding its impact on reef communities, scientists at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and collaborating institutions evaluated the predatory behaviors and diet choices of lionfish in a semi-natural environment.

The invasive lionfish, a voracious predator native to the Indo-Pacific, has become a growing threat to the ecological balance of Atlantic waters. Illustration Credit: Paulette Guardia

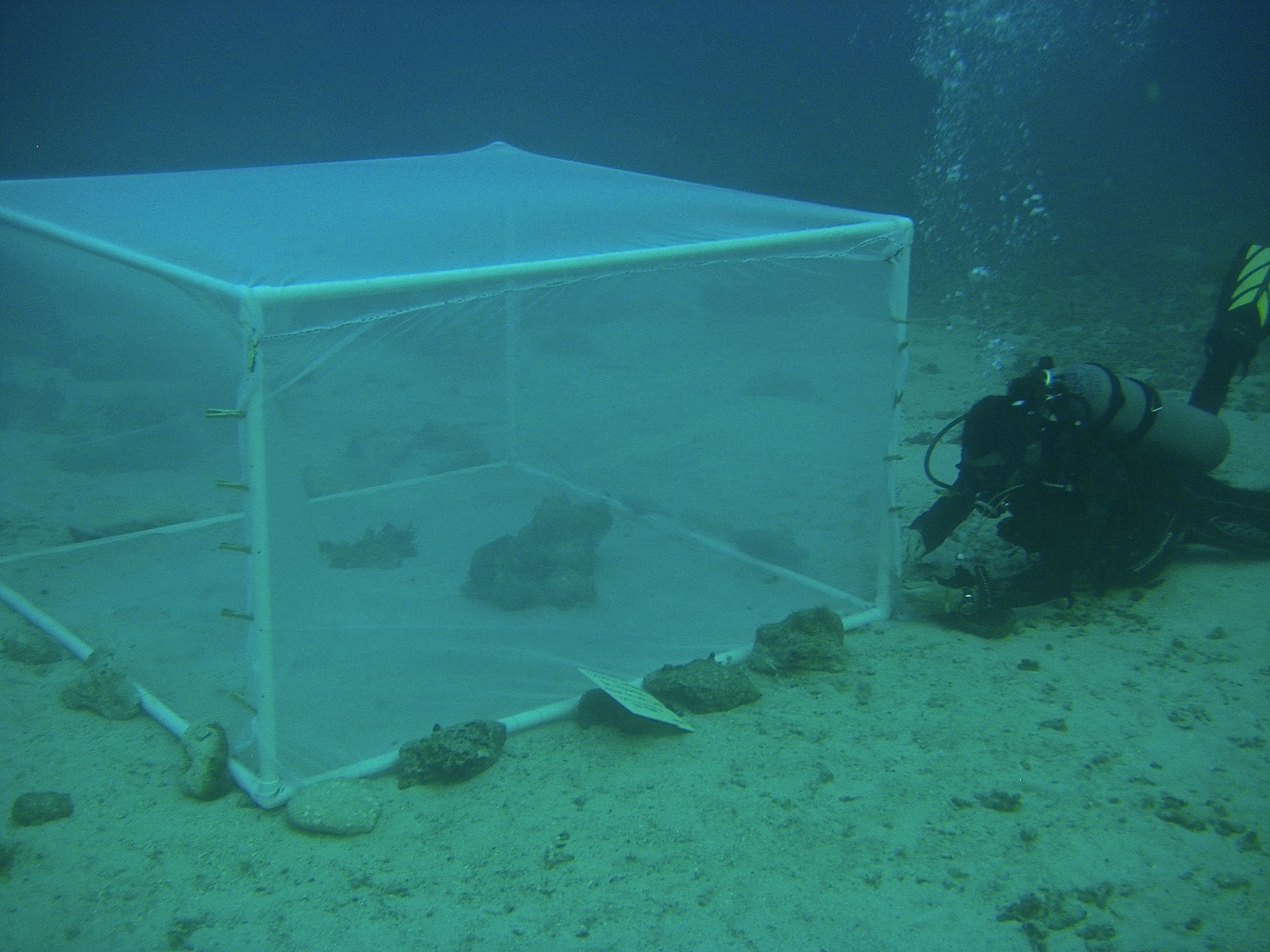

On the fringing reefs of Curacao, hungry lionfish were placed within artificial enclosures designed to simulate natural conditions. Three prey fish species were selected for the trials—brown chromis, bluehead wrasse and masked/glass goby—based on their relative abundance in the reefs and their prevalence in the lionfish diet in Curacao.

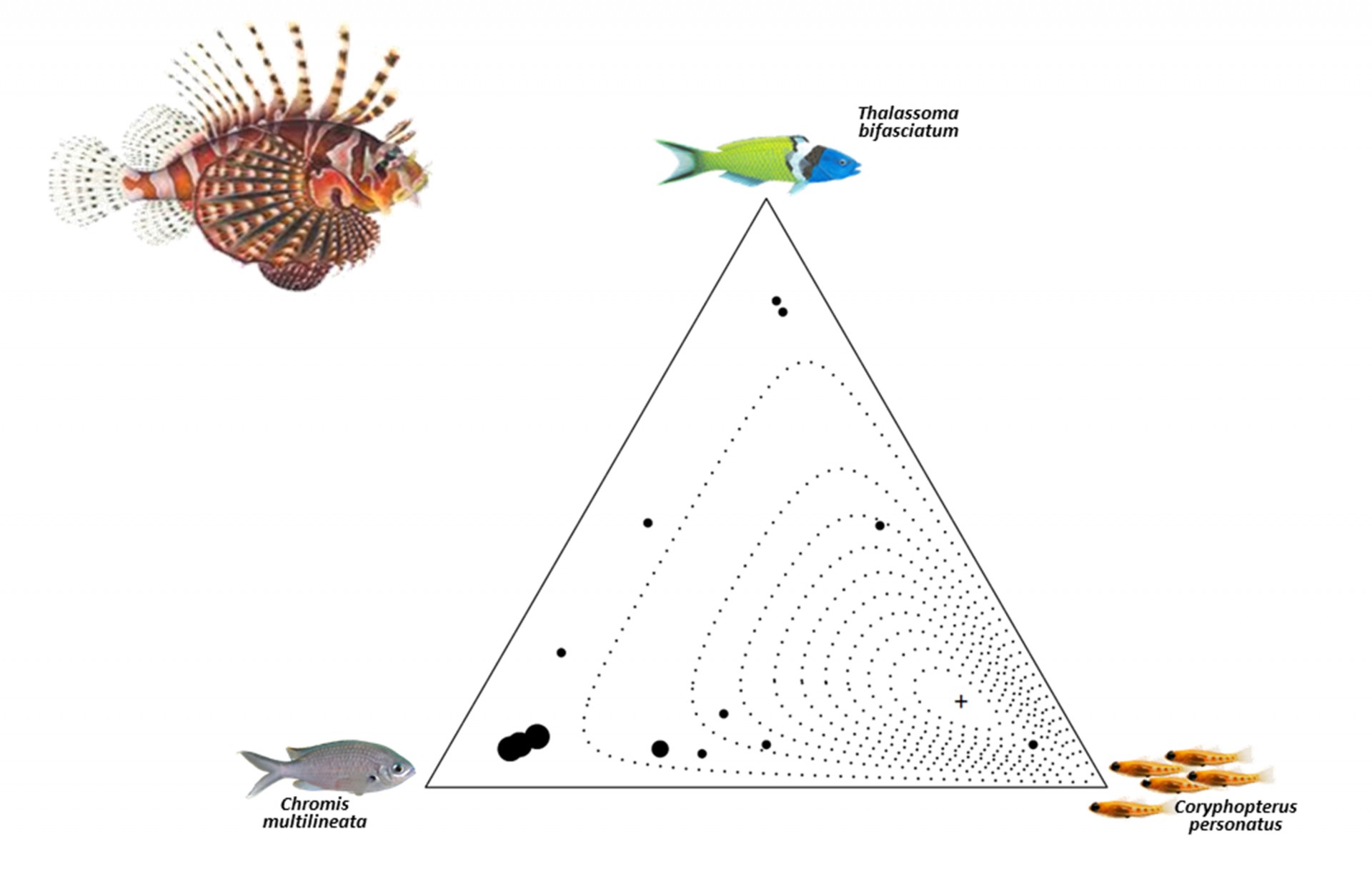

Although the ecological consequences of invasive lionfish are often attributed to their unique predatory strategies and broad diet, the experiments revealed that most lionfish actively selected their prey species, exhibiting a strong preference for the brown chromis over the other two.

To simulate natural conditions, hungry lionfish were placed within artificial enclosures on the fringing reefs of Curacao, with three different prey fish species that are prevalent in their diet. Credit: Amelia Ritger.

These findings, published in the Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, suggest that their foraging behavior is not strictly proportional to prey availability given the abundance of other equally or even more vulnerable species in the enclosure. Alternatively, the scientists noted that lionfish in poorer condition were less selective, often going for the most accessible prey.

“Our study shows active discrimination by lionfish among the top three prey species on Curacao reefs, and an influence of how well-fed an individual was before hunting its prey, on the strength of its preference,” said Michele Pierotti, STRI fellow and senior author of the study. “In other words, as long as they are not starving, lionfish can be very picky about their daily menu.”

Experiments revealed that most lionfish actively selected their prey species, exhibiting a strong preference for the brown chromis over the bluehead wrasse and masked/glass goby.

This represents the first experimental, field-based study to provide direct evidence for active prey choice in this invasive predator. Given the considerable variation in lionfish diet across the invaded range, and the unlikelihood of controlling its continued expansion, further understanding of lionfish diet choices could provide additional insight into their impact on reefs and improve predictions of how they might affect newly invaded communities.

“More researchers might consider using this experimental method—of transforming the field into a working laboratory—to obtain a more accurate representation of what is happening on coral reefs,” said Amelia Ritger, who led the experiment in the field and is now a doctoral student at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “Setting up and maintaining the field enclosures is a lot of work, requiring multiple dives every day, but it certainly pays off.”