Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Fish

Photographers

Extraordinaire

Smithsonian presents first Citizen Scientist award to Allison and Carlos Estapé for contributions to marine research

Extraordinary underwater naturalists contribute unique fish photos to STRI’s Caribbean and Tropical Eastern Pacific Shorefish Apps

A letter dated Sept. 21, 2022, and signed by Ellen Stofan, Smithsonian Undersecretary for Science and Joshua Tewksbury, director of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute recognized the outstanding contributions of Citizen Scientists Carlos and Allison Estapé to the Smithsonian’s research efforts “through your exceptional talents as field photographers and your extraordinary work to capture images of live marine fishes in different parts of the Caribbean and Tropical Eastern Pacific. Your images are a priceless heritage, as a resource for our investigations and for use by scientists, fishers and non-scientist divers who wish to identify fishes. Those images will only become more valuable in the future as documentation of marine life today.”

Searching for Unicorns

Allison and Carlos Estapé’s contributions to science include stunning photographs of fish, like these Golden Hamlets mating; and behind each of their spectacular images, amazing adventure stories wait to be told.

Carlos & Allison Estapé, Darwin’s Pillars, Galapagos. Credit: Sara Chiu.

“We have a gallery of every species we’ve ever photographed, and we’re always adding new photos and species,” says Carlos. “To mostly everyone else, a fish is just another fish, but to us, it could be the Holy Grail.”

He points out a tiny oddscale cardinalfish, Zapogon evermanni, from Roatan, a Caribbean island off of the north coast of Honduras:

“We were swimming into a long cave system in Roatan in about 20 feet of water, among shafts of light streaming down from above. Eventually we came to an especially dark area with narrow chasms in the cave walls, but I couldn’t even get my camera into the cracks. We took turns wedging ourselves into a crack one by one, swimming sideways, and the others would stay outside in the cave to help pull the person back out of the crack. We were really excited to find the fish that we were looking for and it would swim toward our red lights but then it would back off every time someone got close. We were getting low on air, but the fish refused to pose. Everyone was feeling deflated. So, we started to swim back out of the cave system. On the way out I saw a side tunnel and I said…just let me check this one. And there was the cardinalfish posing for a photo! At the time this was a unicorn, as far as we knew.”

How can a fish be a unicorn? Allison explains that fish photographers call a fish that has never been photographed in the wild a unicorn. And for the last several months they’ve been chasing unicorns, first in the Tropical Eastern Pacific near Coiba, Panama, and now in Bocas del Toro on the Caribbean side of the Isthmus.

Both Allison and Carlos grew up watching Jacques Cousteau; both were first certified to dive as teenagers, and both considered careers as marine biologists but ended up going in different directions. Allison was born in the US, and lived in the Panama Canal Zone as a child, and Carlos is of Cuban descent but came to the US as a baby. After they met, they started doing scuba vacations together and in 2008, they got involved in a group called REEF.org.

Carlos Estapé, Allison Estapé, D. Ross Robertson, Alasdair Dunlap-Smith at Bocas del Toro Panama. Credit: Ana Endara, STRI.

“We discovered the REEF Volunteer Fish Survey Project,” says Allison, “REEF’s members are Citizen Scientists who contribute to the largest marine life data base in the world with more than 275,000 citizen surveys to date.”

First, they got involved in surveys to discover the extent of the lionfish invasion in the Caribbean with lionfish researcher, Stephanie Green. Lionfish, voracious predators from the South Pacific and Indian Oceans, eat native reef fish. “To do these lionfish surveys, we had to start learning to identify fish on Caribbean reefs, so we started looking for opportunities to improve our skills.”

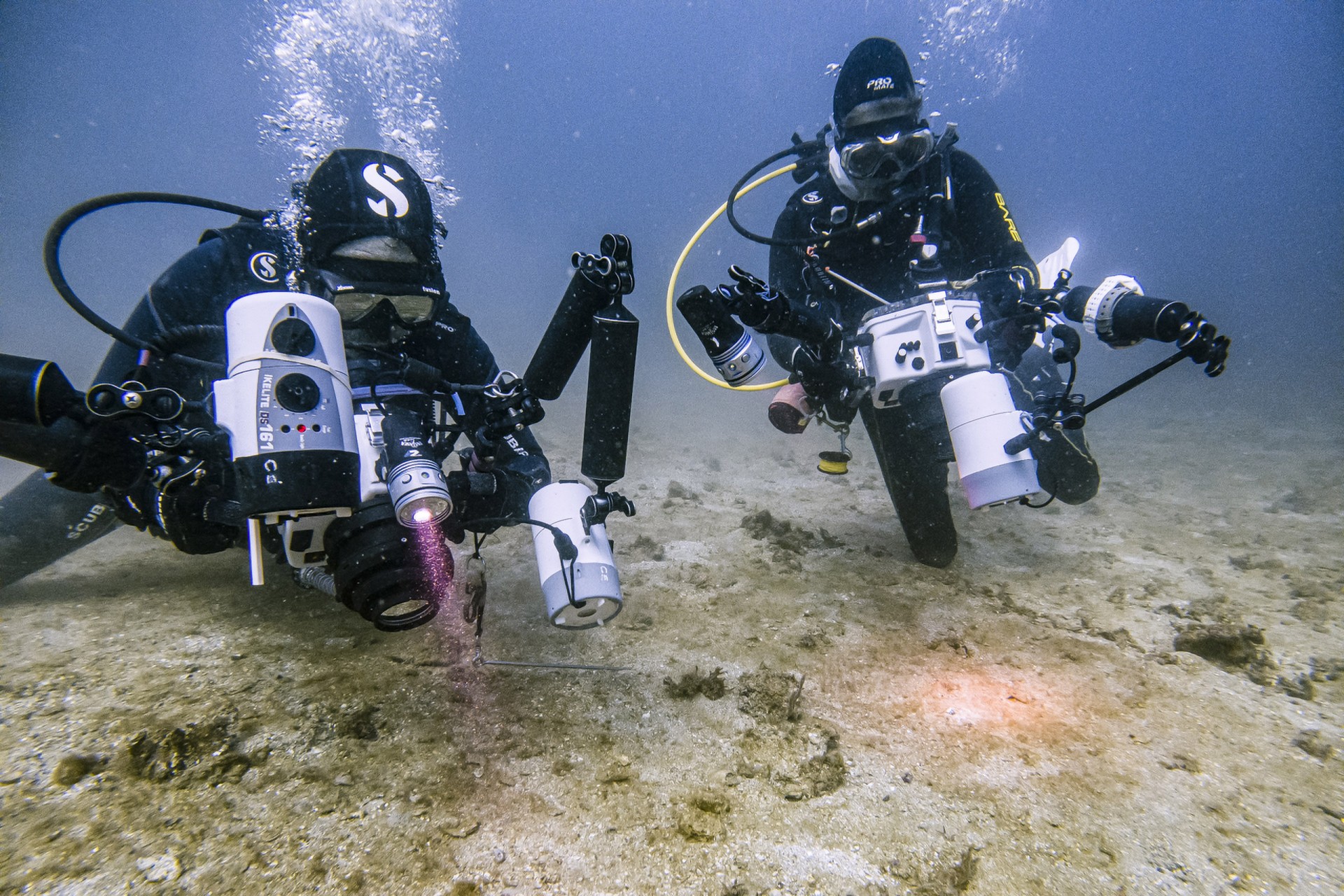

Carlos Estapé, Bocas del Toro, Panama. Credit: Ana Endara, STRI.

Allison Estapé (front), Alasdair Dunlap-Smith (background), Bocas del Toro, Panama. Credit: Ana Endara, STRI.

“One of our friends mentioned a paper by Dr. Walter Starck, who went on to develop underwater photography methods and sophisticated diving equiment, who published a survey of Alligator Reef—very close to where we lived—many years ago. We thought: wouldn’t it be cool to recreate the 1964 Alligator Reef study using photography? We located Walter Starck, and he asked us: ‘Would you like to publish a 50-year update of the paper?’”

This turned out to be a huge piece of work for the Estapés because many of the names of fish had changed, so the first thing they had to do was to update the old list with the new names. They ended up photographing 313 species, 35 species that were not in the original paper.

“We found a lot of species that Starck didn’t find. And this was in our own back yard!”

Eventually work got in the way

Allison left corporate America in 2009 to spend all her time photographing fish.

“We got really excited about photo documenting fish species that had not been previously found in those waters. In St Eustatius we documented/photographed about 40 species, on Alligator reef, about 35 spp., in the US Virgin Islands, 27 species; in Veracruz, Mexico, 7 species. And in the Galapagos, we photographed a fish that had never been documented in the Tropical Eastern Pacific, Acanthurus mata, extending its known range by more than 5,000km range.”

“In 2019 we sold our house and our business,” said Carlos. We asked ourselves “How many years do we have left to follow our passion?”

Ross Robertson

They first heard of Ross Robertson, STRI staff scientist emeritus, back in 2013 when he stumbled across one of their online photos and contacted them to ask if he could use the image for his fish data base.

REEF members create their own challenges and bragging rights: to join their 100 Fish ID Club, potential members must identify 100 fish species on a single 90- to 120-minute dive. This means they need to know what species to expect and ID them quickly. One of the best tools they have as they prepare for these speed ID dives are the two fish identification apps that Ross developed. In 2008, he published a website on Shorefishes of the Tropical Eastern Pacific, and in 2011, he added another on Shorefishes of the Greater Caribbean.

STRI Emeritus scientist, D. Ross Robertson’s web fish ID and iPhone apps: A guide to the Shorefishes of the Tropical Eastern Pacific and A Guide to the Shorefishes of the Caribbean and adjacent areas makes it easy for both scientists and beginners to identify fish to species. Credit: STRI Design Department.

D. Ross Robertson, STRI Staff Scientist Emeritus, Bocas del Toro, Panama. Credit: Ana Endara, STRI.

Now, these are iPhone apps that make it simple to browse images of fish organized by species or by family, to search for species ID’s using easily observed characteristics like color and shape and to keep track of fish as one sees them and to create and export lists of fish and regional maps.

“For this trip to Bocas del Toro we were targeting 51 species that we had not seen before. Of those, we found 10 and a few others beyond our original list that we did not expect to find,” Carlos said.

Ross was thrilled that such amazing photographers were donating their own time to photograph fish for the data bases, and the Estapés were thrilled to help him:

“We talk to Ross and ask him ‘where do you want us to go now” [Research scientists use Ross’s app as they study fish behavior, and help policy makers define new marine protected areas. Often there are only very poor photos of the fish in these areas, or the fish have never been documented in the wild before, giving the Estapés the first opportunity to photograph the unicorns.]

Now Allison and Carlos take the prize as the leading Citizen Scientists Contributors to his web pages. So far they have contributed around 2000 of the 17,000 species images to the Caribbean pages and at least 1000 of the 11,000 images on the Tropical Eastern Pacific pages.

“Carlos and Allison, both of whom are excellent underwater photographers, have made a huge contribution to scientific knowledge about neotropical shorefishes by photographing reef fishes in their natural habitats,” says Ross. “They have aimed to obtain taxonomically useful images that show key features for identifying different species, and that show how much species can vary in their appearance due to their age, sex, behavior, the habitat in which they are found and their location within their geographic ranges. Those photographs also act as vouchers to show exactly where in either the Greater Caribbean or Tropical Eastern Pacific species occur.”

As the Estapes and their friends photograph live animals in their natural habitats, they contribute to science, improving our understanding of where a particular species lives (its’ geographic range).

They photograph fish that others have missed because they blend in so well with their surroundings (called cryptobenthic species) or species that only live in deep water, or in the open ocean.

Because they have learned what characteristics scientists use to identify fish, they can take ‘diagnostic images’, and by recording behavior, mating colors and the wide range of colors and forms exhibited by a single species, they may clarify the difference between species that were once thought to be the same. They work with Ben Victor, whose specialty is the larval forms of Caribbean fish, to add to the Barcode of Life project. Because larval forms may look so different from adult forms, they learned from him that the gold-standard of data collection is not only to take a photo but also to collect a specimen and a DNA sample, but this is only possible when they work hand in hand with scientists who have collection permits.

Sailfin signal blennies, Coiba & Las Perlas, Panama

“No spine, no time:” Completely focused on fish

Rachel Collin, STRI staff scientists and director of the Bocas del Toro Research Station, met the Estapés during their recent visit. “I told them there were some amazing nemerteans (ribbon worms) that they could photograph, and they told me that they only photograph fish. They have a saying: ‘No spine, no time.’” She also confirmed that they seem extremely happy. Unlike professional scientists, who also either spend time teaching at a university or have other administrative responsibilities, by choosing to follow their passion, they dedicate most of their time to doing exactly what they love.

Ross joined them for two weeks in Bocas del Toro; this was their 7th trip together, but their first time in Bocas. One of their objectives was to photograph Hamlets with scientists who are interested in how their bright colors and behavior leads to their speciation. And their other objective? To find more unicorns, especially highly cryptic species that live in mangroves and muddy environments.

On Monday, Carlos and his friend Alasdair Dunlap-Smith spent five hours in a creek in the mangroves.

“We found a lyre goby…we had been hunting for it for a decade. They live in burrows in shallow, muddy creeks. Alistair has a point and shoot that we can stick down into the water. That fish has eluded us for a while. There are some photos but none as good as Alasdair’s.”

A little help from their friends

Wherever they go, the Estapés always have a lot of help from local guides and dive shops. “We rely so much on local knowledge, friends, because the low-hanging fruit has been picked. Now we are looking at cryptobenthic species and fish with small ranges. We have to go look for endemics.” In Panama’s Tropical Eastern Pacific, they worked with local guides: Feliciano Piedra & Carlos Camaño and the Panama Dive Center in Santa Catalina. In Las Perlas, they worked with Guillermo Schuttke at the Coral Dreams dive shop. And in Bocas del Toro their dive guides were Eliumer (Pino) Rios Smith and Roosevelt (Chombo) Diaz and the Bocas Adventures dive shop owned by Eddie Ibarra.

The hunt for the Darkspotted Jawfish, Bocas del Toro

“A local guy, Till Deus, (used to work at STRI) is developing a method to grow anemones for the aquarium trade. This would provide a sustainable income for locals and could replace fishing for more and more scarce fish.” Till breeds only local fish species, hard corals and anemones.

Scientists can’t be everywhere at once, but Citizen Scientists can find a lot of variation and document what things look like in different places.

The hunt for clingfish, Bocas del Toro

More fish in the sea?

The Estapes have taken more than 45,000 images and their species list is just shy of 1500 species. Are there still more fish to photograph?

Yes!

“There are estimated to be more than 30,000 fish species in the world,” says Carlos, “So far we have focused on the diver subset—the fish most easily observed by divers—and we’ve photographed about 600 species in the Atlantic and 400 in the Tropical Eastern Pacific.” They also seize opportunities to photograph brackish water fish which are included in Ross’ website/apps.

And not only do the Estapés often inspire other volunteers by giving talks about their own work, they also offer training sessions for fish photographers who are interested in joining in the fun. They take people diving to photograph Hamlets, some of the most colorful fish on reefs. They love to evangelize, encouraging photographers to post their images online and make them available to scientists. While they were in Panama, they agreed to give a webinar as part of the series offered by the STRI Bocas del Toro research station.

Thrilled to be able to help professional marine biologists, they were very grateful for the award: “We love what we do with the Smithsonian. It gives our diving purpose. We love to contribute to science.”

Their award letter concludes: “Please accept our gratitude on behalf of the Smithsonian for the highly significant contributions you have made as Citizen Scientists to advancing our mission for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.”

Resources

Photo shelter site

https://carlosestape.photoshelter.com/

Bio on the STRI Fishes Tropical Western

https://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/caribbean/en/contributors/citizen_scientists#4