Mutualism under pressure: new research in Panama shows a plant’s ability to keep its defender ants happy

Litter please!

How fallen leaves sustain tropical forests

By Leila Nilipour

Decomposing Foliage: A 17-Year Study Unravels the Vital Nutrient Exchange in Tropical Forests of Panama.

The noise of leaf blowers always seems to disrupt us in the worst possible moments. Blowing tree litter off patios, sidewalks, and driveways is commonly observed in suburban areas. Although it may not be aesthetically pleasing to look at for some, those fallen leaves are helping trees grow naturally. Researchers from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and collaborating institutions actually spent 17 years moving litter around a forest in Panama to understand how it works. Their findings were published in the Journal of Ecology.

Tropical forests are among the most important ecosystems for combating global warming. Yet many of them grow on infertile soils. Scientists believed that trees could be reutilizing the nutrients in litterfall to continue growing in poor-quality ground but didn’t have direct evidence to prove it. Previous studies hadn’t been able to explore the question in a sufficiently large area or for long enough to assess the role of fallen leaves in tropical forests.

Francisco Valdez supported the study by moving litter around Panama’s tropical forests for over a decade.

Credit: Emma Sayer, Ulm University

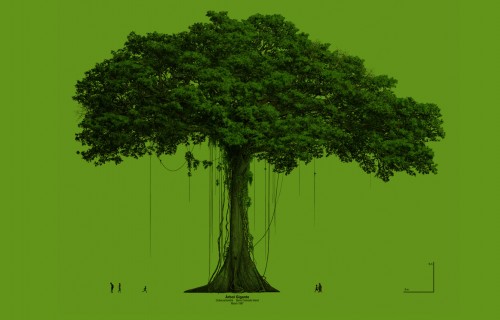

To explore this theory, the Gigante Litter Manipulation Project (GLiMP) team worked in a tropical forest in Panama for nearly two decades. They took away dead leaves and plant material from some areas and put more in others. In other words, some trees got less litter than usual, while others got more - for 17 years.

The experiment was something co-author Edmund Tanner (Cambridge University and STRI) had long wanted to do – since starting forest fertilization trials in Jamaica in the 1980s. However, locating a suitable site and an organization that would support a long-term experiment proved challenging. Unlike fertilizer studies, which can persist with just an annual visit, sustained effort is essential for litter removal trials; as soon as you stop removing litter, the experiment slowly dies.

“The biggest challenge has been keeping the experiment running for long enough to measure changes in tree growth,” said lead author Emma Sayer, from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), Ulm University and Lancaster University.

In areas where the litter was removed, the trees didn't grow as well over time; eventually, they also started producing less litter. On the other hand, in areas with extra litter, the trees just showed a small, temporary increase in growth at the start of the experiment; after that, the extra litter only resulted in increased annual litterfall.

Trees in the areas of the forest that had their litter removed didn't grow as well over time.

Credit: Emma Sayer, Ulm University

Former University of Cambridge student Laura Sutcliffe taking measurements of the walking palm (Socratea exorrhiza).

Credit: Emma Sayer, Ulm University

The trees with decreased litter may have found ways to cope with fewer nutrients over time. For instance, they changed their mycorrhizal fungal partners, which may have given them access to more nutrients from the soil. Another way they could have responded was by making their existing leaves last longer or by producing fewer new leaves and roots.

Overall, the results of the experiment revealed that the process of leaves falling and decomposing on the ground provides nutrients to the soil that help promote tree growth in otherwise infertile tropical forests.

“The size of the plots and the long duration of the experiment make it unique, and allowed us to test a theory that has remained untested for almost 40 years,” said Sayer. “STRI’s support for the experiment has been invaluable for achieving this.”

A 17-year-long study in forests of the Barro Colorado Natural Monument determined that the nutrients in leaf litter help promote tree growth in otherwise infertile tropical forest soils.

Credit: Steven Paton, STRI

The trees that had the litter removed, and thus received fewer nutrients over time, changed their mycorrhizal fungal partners, which may have given them access to more nutrients from the soil.

Credit: Steven Paton, STRI

Headquartered in Panama, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. The institute furthers the understanding of tropical biodiversity and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems.