Leafcutter ants have blind

spots, just like truck drivers

Integration

Are rivers

guilty?

Bocas del Toro

Text and photos by Leila Nilipour

A unique project, integrating river and oceanic data, aims to shed light onto the drivers of marine hypoxia

During certain times of the year, Almirante Bay, a semi-enclosed body of salt water surrounded by the islands of the Bocas del Toro archipelago in Panama, experiences hypoxia. This lack of oxygen, affecting the diversity and productivity of life in the Bay, may be caused by a combination of human activities and climate change: the runoff of polluted water from rivers into the ocean, aggravated by the higher frequency of storms and large rain events. If the periods of hypoxia start becoming longer, this Caribbean sanctuary could eventually turn into a “dead zone”: a place in which no life exists.

Hoping to better understand the role rivers play in this phenomenon, biogeochemist and STRI postdoctoral fellow KC Clark exits on a small boat from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s (STRI) dock at the Bocas del Toro research station on Isla Colon. It motors towards the mainland, where several rivers flow into Almirante Bay. She is on her way to discover more about these tributaries, alongside Ximena Boza, a technician for MarineGeo, a global network studying nearshore marine life.

At around 8:40 a.m. they arrive at a brown river. Despite the fact that it is called Rio Banano, there are no banana plants to be seen, but plenty of mangroves. Several minutes into the waterway, a large fallen tree prevents further transit and serves as the inevitable stopping point. Clark and Boza start pulling out the different tools and sensors from duffle bags in the bottom of the boat.

“The idea is to select a location on each river and go back every two weeks to repeat the measurements. I marked the spot with a GPS,” says Clark.

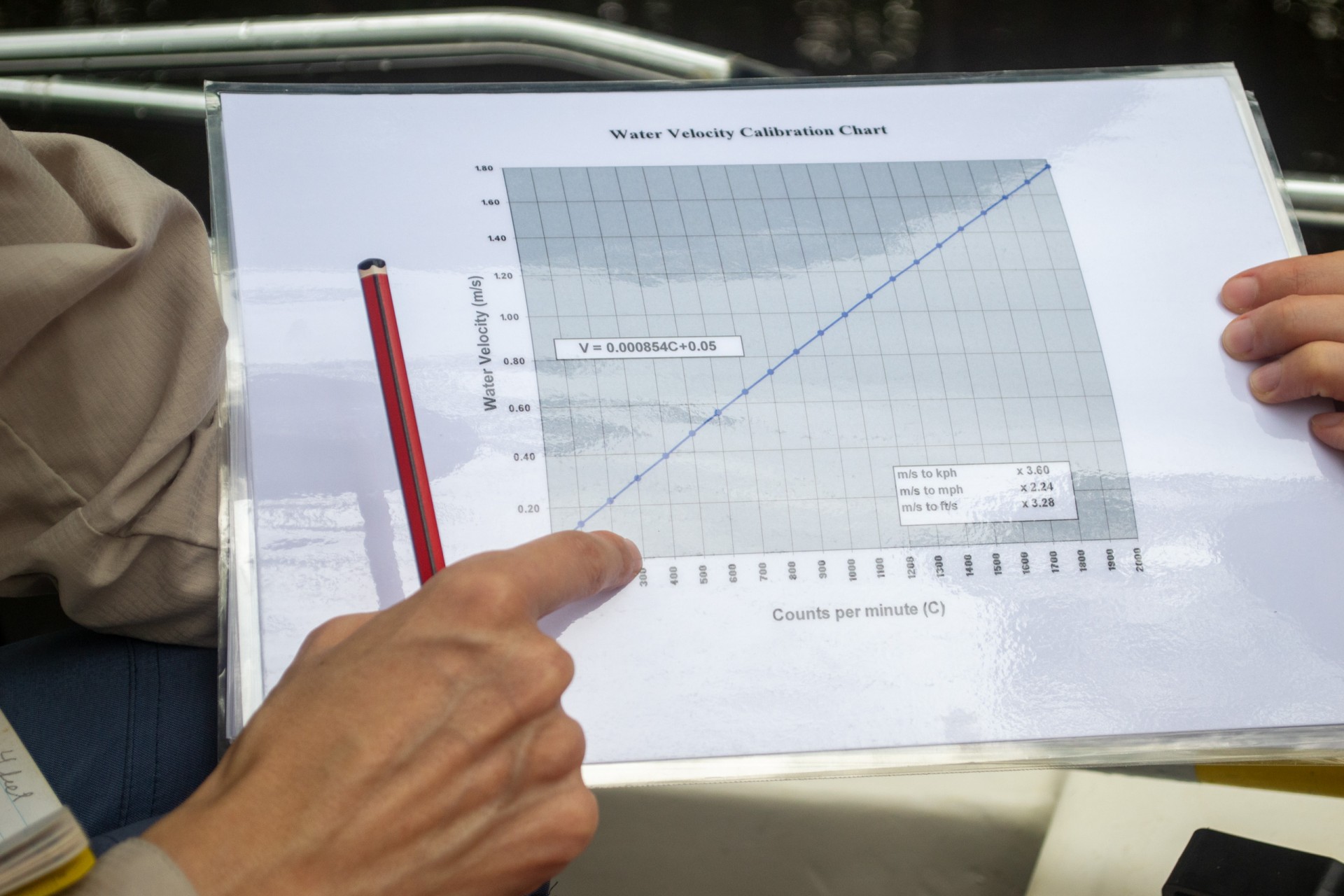

Over the next hour and a half, they measure the depth and width of the river, as well as temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH and salinity. They also determine the velocity of the water flow. Coupled with river level sensors that record the depth of the different rivers every five minutes, Clark can calculate the amount of water discharged into the bay.

It takes a long time to complete all the measurements for the first time in río Banano. The protocols are being fine-tuned before repeating them in six other rivers. At the next stop, an unnamed river they baptize as Río Negro —because of its black waters—, the whole process goes much faster.

“The issue will be trying to identify what might be the conditions that create this hypoxia. In this river, for example, the water is fresh but it is hypoxic. It smells rotten,” she points out. In other words, the salinity is low, but there is little oxygen in the water, so most organisms can’t survive.

Out in the bay, mangrove forests and seagrass fields rely on the flow of nutrients from the rivers, but coral reefs are vulnerable. They need clear water, low in nutrients, to survive. Storm events that increase the flow of water, carry additional nutrients and organic matter into the bay. This, in turn, promotes the growth of phytoplankton or microscopic marine algae, increasing both food availability for microbes and their oxygen demand.

In the bay, river water and rain can form a layer on top of the marine water, causing vertical stratification, with higher temperature waters and low oxygen levels at the bottom. This process can ultimately generate hypoxic conditions and contribute to coral bleaching and mortality in Almirante Bay.

The next stop of the day is along a canal that connects with the mouth of the Changuinola river. There are no mangrove trees, but there is a more varied vegetation, with grass, bamboo plants, ferns, tropical water lilies, the rare Rafia palm that only lives in this region in Panama, and even guaba trees. By the time all the measurements are completed, it is after 3:00 p.m. and raining, which is perfect for the measurements, but challenging to travel in. The small boat—ideal for navigating the shallow river waters—, is very jumpy in the agitated ocean. The operator anchors in a nearby island on its way back to the station, allowing the waves to settle.

But no matter what the weather conditions are, the six rivers will be sampled every two weeks for over a year and their measurements compared to the data gathered by a parallel project studying the physical parameters and nutrients in Almirante Bay. This interdisciplinary initiative, integrating riverine and marine components to understand the drivers of hypoxia in the ocean, is unique in the tropical Americas and the results may have wide-reaching applications in other tropical marine coastal areas.