Smithsonian science helps understand blue whale migratory and foraging patterns to inform conservation strategies

Half

a century

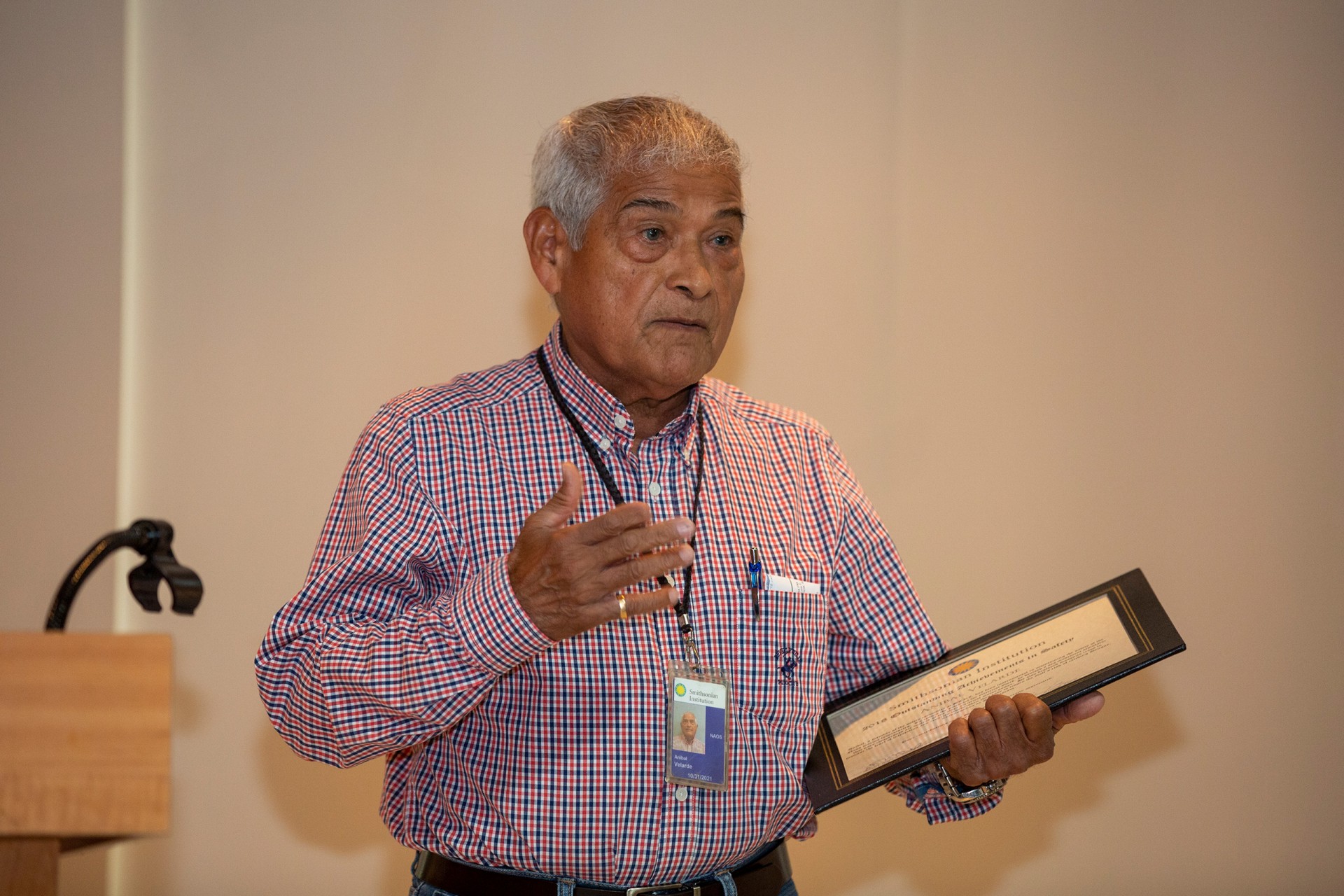

From aquarist to star inventor

Naos

Text by Leila Nilipour

What started as a student summer job, became Anibal Velarde’s life’s work. Over fifty years later, he is still at the Smithsonian

Before the clock strikes three in the morning, Anibal Velarde is already preparing his coffee and a sandwich for breakfast. He likes to leave the house while it is still dark and face the calm of the morning, during his journey from Panama City’s Juan Diaz neighborhood to Amador, at the Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal. Around half past four, he is already starting his day at STRI’s Marine Laboratories on Naos Island: a schedule he assigned himself.

This has been his second home since 1967, when he was a biology student hired to take care of the aquaria. But even before college, he was inspired by the marine world. During his childhood, in Veraguas, he frequently sailed from Puerto Mutis, fishing from his uncles’ boat.

Anibal is slight in stature, with dark skin and light eyes. A bunch of keys hang from his jeans. With them he seems to be able to open all the doors in the building. For the interview, he mentally travels several decades in the past. “There used to be a workshop here,” he recalls as he walks the halls. "Over here, the train used to pass," he says, pointing to the floor, where the rails are still marked. He carries a folder under his arm and opens it to reveal dozens of black and white photos and his resume.

He was born in 1944. The document reflects over half a century at STRI. And the images portray the days he remembers with the greatest affection: when he supported the scientists Peter Glynn and Ira Rubinoff, taking underwater notes while diving, sitting in a boat with a huge shark at his feet and placing a harness on a sea snake. That was one of his first inventions, designed to make the scientists’ job easier.

"We used to study Panama's poisonous sea snake, Pelamis platurus," says Anibal, about his years with Dr. Rubinoff. "I made a floating harness that carried a small transmitter without directly sticking it to its belly."

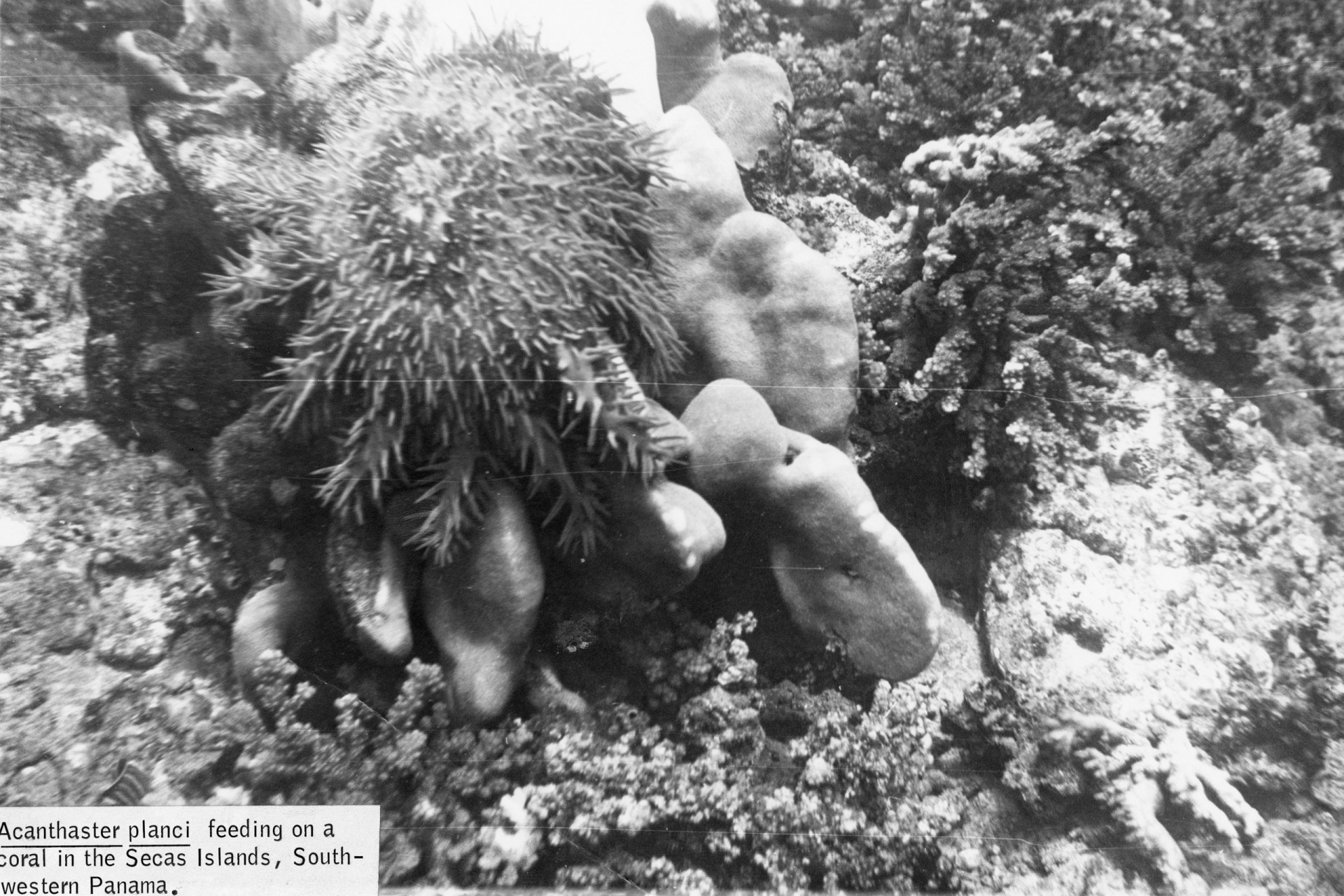

His work, alongside Peter Glynn, led him to dive as far away as the seas of Oman. The sultanate sent them to solve a problem they had with the ‘crown of thorns’ starfish. In addition to the Gulf of Oman, the species also inhabits the Pacific Ocean off of the coast of Panama’s Chiriquí province and feeds mainly on corals. In the Arab country, it was destroying the reefs.

"They were quite satisfied with the study," he says, smiling. “The work was hard, but the results were positive. At the end of it all, that was the purpose of the mission.”

Anibal was restless since his childhood. To prove it, he shows a severed finger. He lost its tip when he was eight years old, while playing with a mill to extract sugar cane juice at his grandfather's estate. That restlessness and his ingenuity led him to develop various structural solutions for the scientific challenges he encountered along the way. One of them earned him a recognition at the Outstanding Achievements in Safety Awards from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

“Here they joke about why they didn't give me the title of scientific engineer,” he says.

His flagship invention is in use in an open area of Naos Marine Laboratories. It is a rotating PVC structure, almost completely submerged in a water-filled tank. With air bubbles emerging from the bottom of the tank and a jet of water falling from above, the structure turns like a Ferris wheel. Inside it are several bottles filled with seawater and larvae. The rotating movement simulates natural wave action or a strong current, and ensures that the larvae remain alive during the experiment.

"We had to simulate that they were in the ocean, so I designed this system without electricity, using what was on hand: the air bubbles and water coming from the dock," he explains. "Since it has sea water, we wanted to avoid running it with electricity because it is dangerous."

In 2000, Anibal decided to retire. He trained his replacement and left his first and only job. Five years later, he was called to come back. He was planning to stay for six months, but fourteen years have passed.

And although he is proud to have worked at the Smithsonian, because he believes he contributed his grain of sand to try to improve the world, he plans to retire soon, while he is still healthy.

“I feel good, I am fit and I have the courage to do the things I still want to do,” he confesses. "For example, internal tourism with my wife: go to Las Tablas, stay in a hotel, walk around, talk to people and buy souvenirs."

This news story is aligned with the

Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations.