For the first time since records began,

the cold, nutrient-rich waters of the

Gulf of Panama failed to emerge

GEO-Trees

A revolution in forest carbon verification

Panama

Byline: Leila Nilipour

The new GEO-TREES initiative addresses the uncertainty of satellite estimates of forest carbon by creating a trustworthy global carbon verification system based on existing collaborations among scientists at forest research sites worldwide. Supported by the Bezos Earth Fund, all data will be available free, online.

Tropical forests are among the most carbon-rich and biodiverse ecosystems in the world. However, three-quarters of the world’s studies of plant demographics are from temperate areas, where most researchers are based. Such knowledge gaps severely limit management decision-making in some of the most critical habitats for the health of our planet.

Tipping the balance in favor of tropical forest science requires a greater investment in technologies and training in the tropics. With a $12 million gift from the Bezos Earth Fund, the new GEO-TREES initiative is positioned to do just that, in partnership with space agencies and leveraging over four decades of global forest research experience by the ForestGEO network, the Smithsonian’s Forest Global Earth Observatory.

The initiative will be officially launched on December 8th at the Nature Positive Pavilion in COP 28, the UN Climate Change Conference, during the panel “From Ground to Space - The Future of Forest Carbon” co-hosted by the Smithsonian, the Bezos Earth Fund, the World Resources Institute, and the European Space Agency. At the core of its mission is the creation of a standard system for carbon verification worldwide.

A universal standard

“There is no standard method for measuring carbon across all forests around the world,” said Stuart Davies, ForestGEO director.

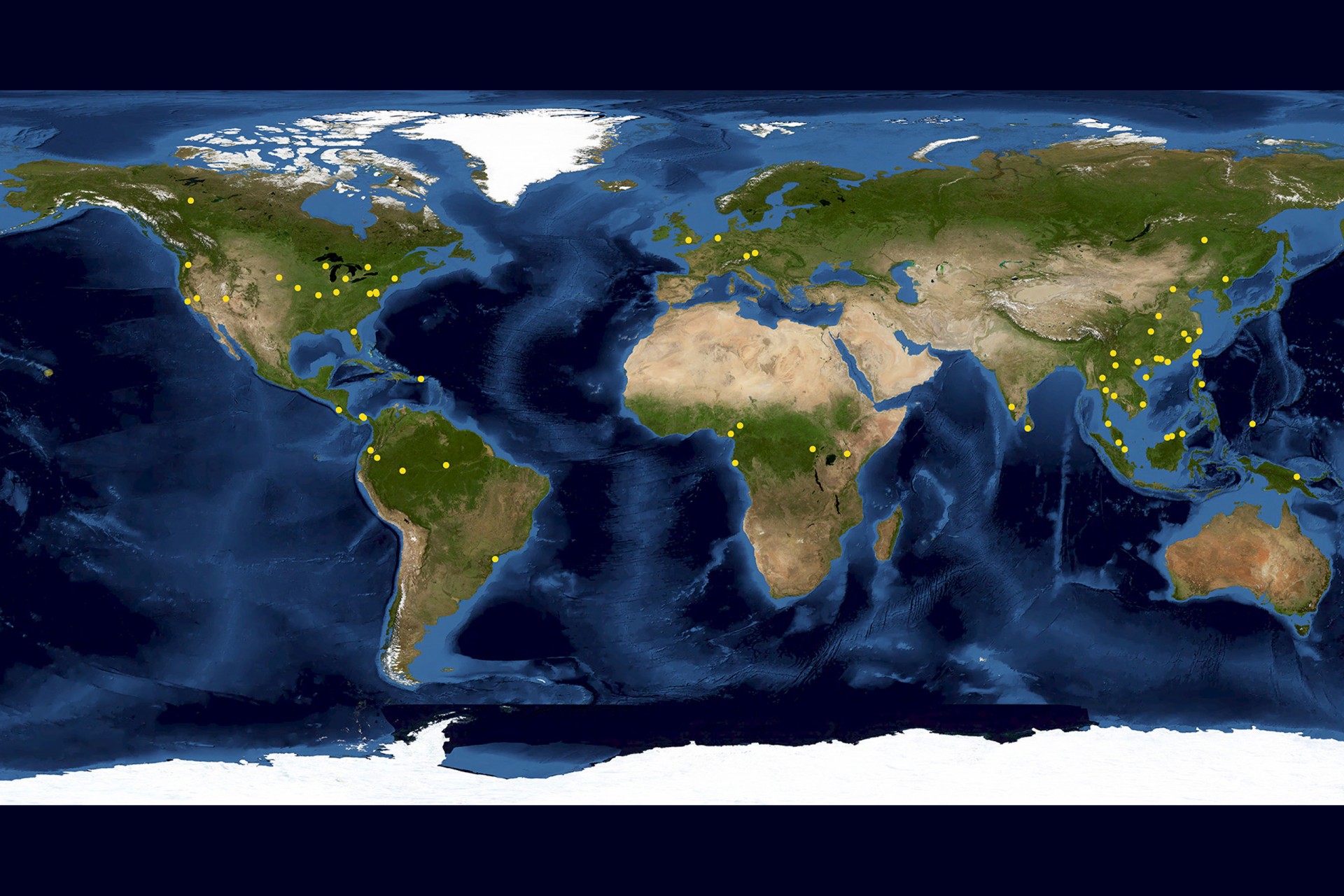

Part of this relates to the wide variability of forest types and tree species within them, especially in the tropics. GEO-TREES will establish over 100 study sites in tropical and temperate forests worldwide, including mature, degraded, and recovering secondary ones, to address this variability.

“There isn't really any one kind of tropical forest,” said STRI staff scientist Helene Muller-Landau. “There is a big diversity of structure and species composition as well. Because of that, we also have very different forest carbon stocks in different forests.”

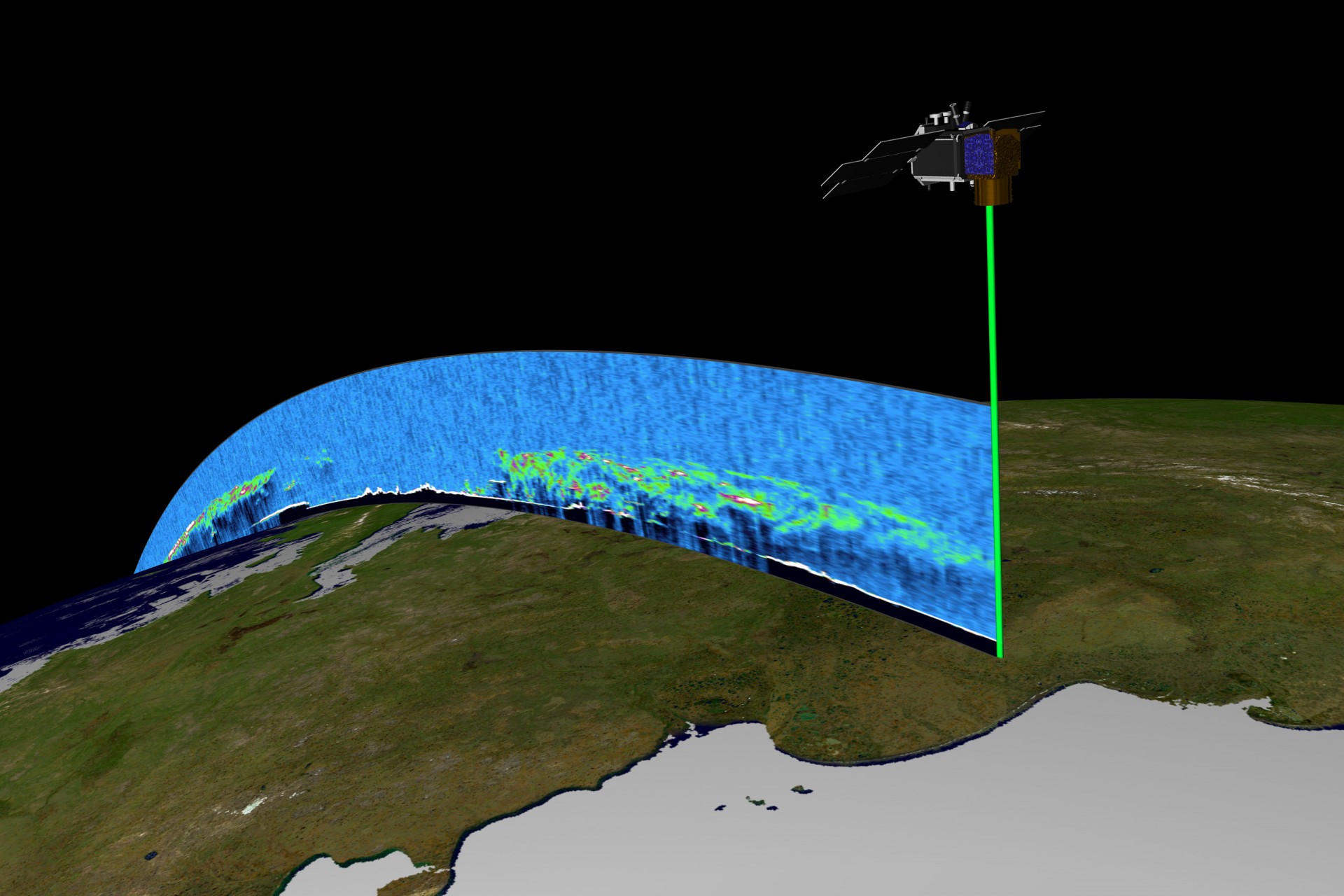

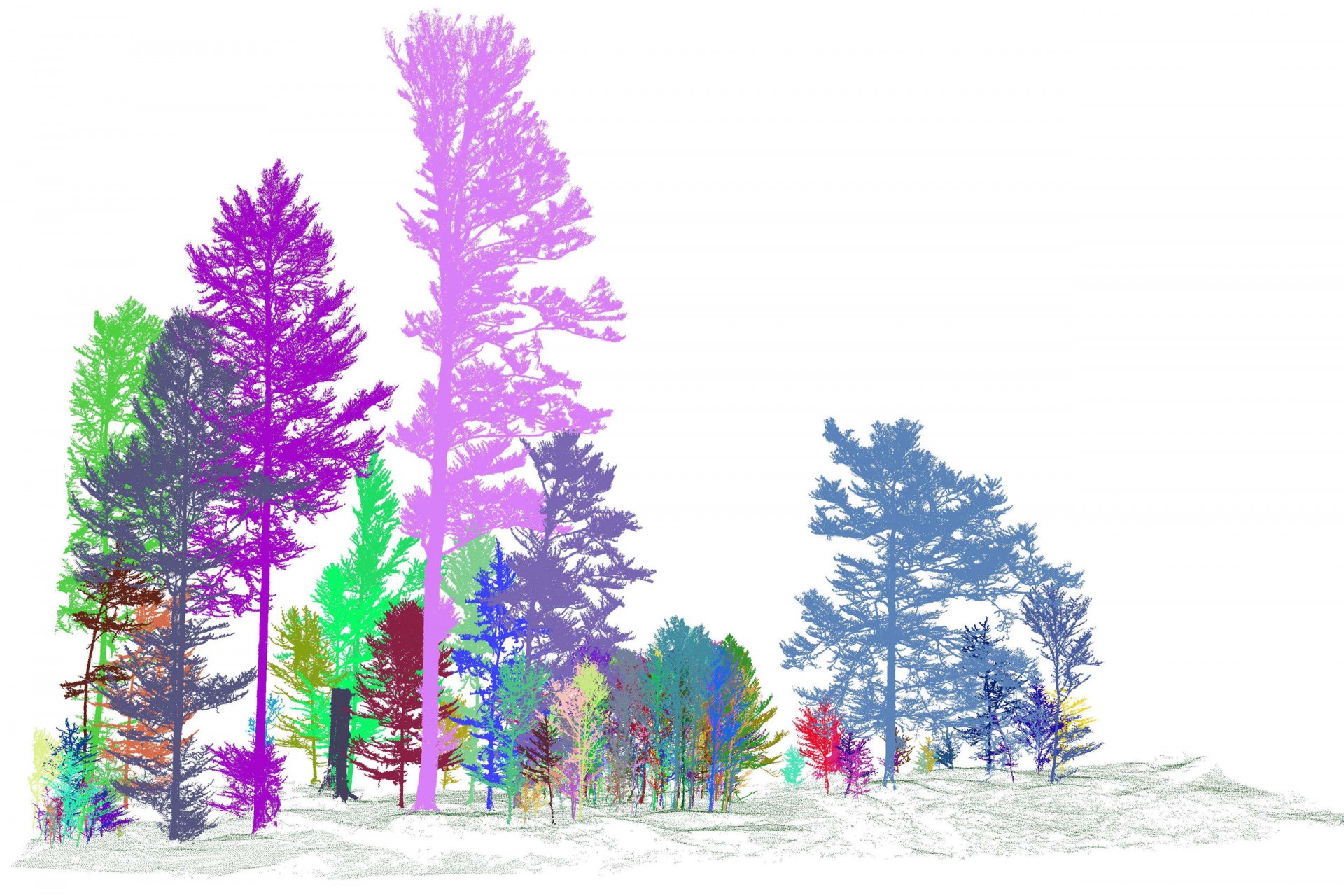

To accurately estimate their carbon storage capacity, local forest scientists will repeatedly measure the trees in these plots manually and through terrestrial and airborne laser-scanning devices.

Measuring all the trees in a tropical forest plot over time is not new. It began on a 50-hectare plot in Panama’s Barro Colorado Island in 1980 and eventually expanded to the 76 forest-research sites in 29 countries comprising the ForestGEO network. Space agencies have more recently joined these efforts, leveraging their satellites to measure the size of forests and infer how much carbon is in them.

However, scientists have expressed their concerns with the accuracy of satellite estimates primarily because space agencies have not invested in ground measurements to calibrate their sensors.

“Remote-sensing estimates to quantify carbon losses from global forests are characterized by considerable uncertainty and we lack a comprehensive ground-sourced evaluation to benchmark these estimates,” said the authors of a recent paper in Nature.

Understanding how much carbon is stored in different forests during accelerated warming is critical for land managers, scientists, and carbon clients —those interested in offsetting their carbon dioxide emissions by buying carbon credits from organizations or groups that sequester or reduce emissions.

GEO-TREES' partnership with space agencies aims to validate these satellite observations with ground-based measurements to help overcome the uncertainties in forest carbon storage estimation and bolster large-scale global investments in forest protection and restoration.

Local scientists and communities

GEO-TREES is people-centered, focused on involving local communities in their research projects and building capacity in many lower-income countries where research sites have already been established. Significant funds will go into training local foresters in using innovative technology, such as laser-scanning devices that measure forest carbon from the ground.

“GEO-TREES is a prime example of how the Smithsonian’s ‘Life on a Sustainable Planet’ initiative is about creating the maximum positive impact for ecosystems and the communities within and around them,” said Ellen Stofan, Smithsonian Under Secretary for Science and Research.

With information gathered from the long-term monitoring of millions of trees in forests worldwide, GEO-TREES will ultimately create and sustain an open-access database that provides the foundation for the different actors involved in devising strategies to mitigate climate change.

“We need to use every tool in our toolbox to pull carbon out of the atmosphere today to create a sustainable future for tomorrow,” said Joshua Tewksbury, director of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.