Marine resource use has influenced human population on the Central American Isthmus for millennia

Gallant

Storyteller

Anthony G. Coates,

Senior Scientist Emeritus (1936-2022)

Byline: Beth King

Geologist Tony Coates changed the way we think about the ground under our feet. He confirmed the date when North and South America were connected at about 3 million years ago. We remember Tony not only as a skilled field geologist, but as a kind person and storyteller, who captured the imagination of scientists and non-scientists alike with his ability to spin a tale.

Equally at ease chatting with barefooted kids on a beach in a Caribbean backwater town, or sipping something on a donor’s yacht, Tony Coates was happiest with a fossil in his hand, transporting whoever would listen to another time.

Tony came from England, which became an island about 14,000 years ago as the glaciers of the last great ice age melted and sea level rose. After graduating from King’s College at the University of London with honors in geology, he traveled to France and wrote his doctoral thesis as a student both at the University of London and the University of Caen in Normandy, already intrigued by the geological forces shaping the edges of continents.

Tony playing cricket in London in 1957. To his delight he later landed a spot on the Jamaican All-Star cricket team. Credit: Courtesy Tony Coates.

Tony joined the Jamaican Geological Survey in 1962. Jamaica is built upon an island arc above a subduction zone. Credit: Modified from Google Maps.

He began his career as a geologist in the Caribbean, travelling to join the Jamaican Geological Survey in 1962, and staying on as an assistant professor at the University of the West Indies. Jamaica forms part of an island arc and Tony was especially interested in the accumulations of extinct rudist clams that once grew in the shallow water around the island when the dinosaurs still walked the Earth, as biomarkers indicating past changes in sea level, volcanic activity, and the formation of arc-shelves.

Tony’s Early Years

From Jamaica, Tony moved to Washington D.C. in 1966 to teach geology at George Washington University, where he created a graduate program in geobiology drawing on resources from the Smithsonian and other Federal agencies. In 1986, he shifted from teaching to full-time administration as Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies. He made everyone’s lives easier by improving research and teaching fellowships for graduate students, digitizing all registrar functions, negotiating the return of a portion of grant overheads to scientists, and developing competitive research grants for faculty: in each case putting people first and creating systems that worked for them.

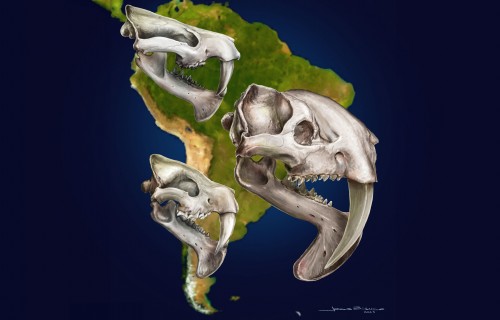

Jeremy Jackson, marine biologist, now senior staff scientist emeritus at STRI, asked Tony to come to Panama to study the origin of the land bridge between North and South America in 1988. They co-founded the Panama Paleontology Project (PPP), which convened 40 scientists working in 8 countries to understand the significant global changes caused by the Isthmus of Panama such as unprecedented migrations of animals between continents.

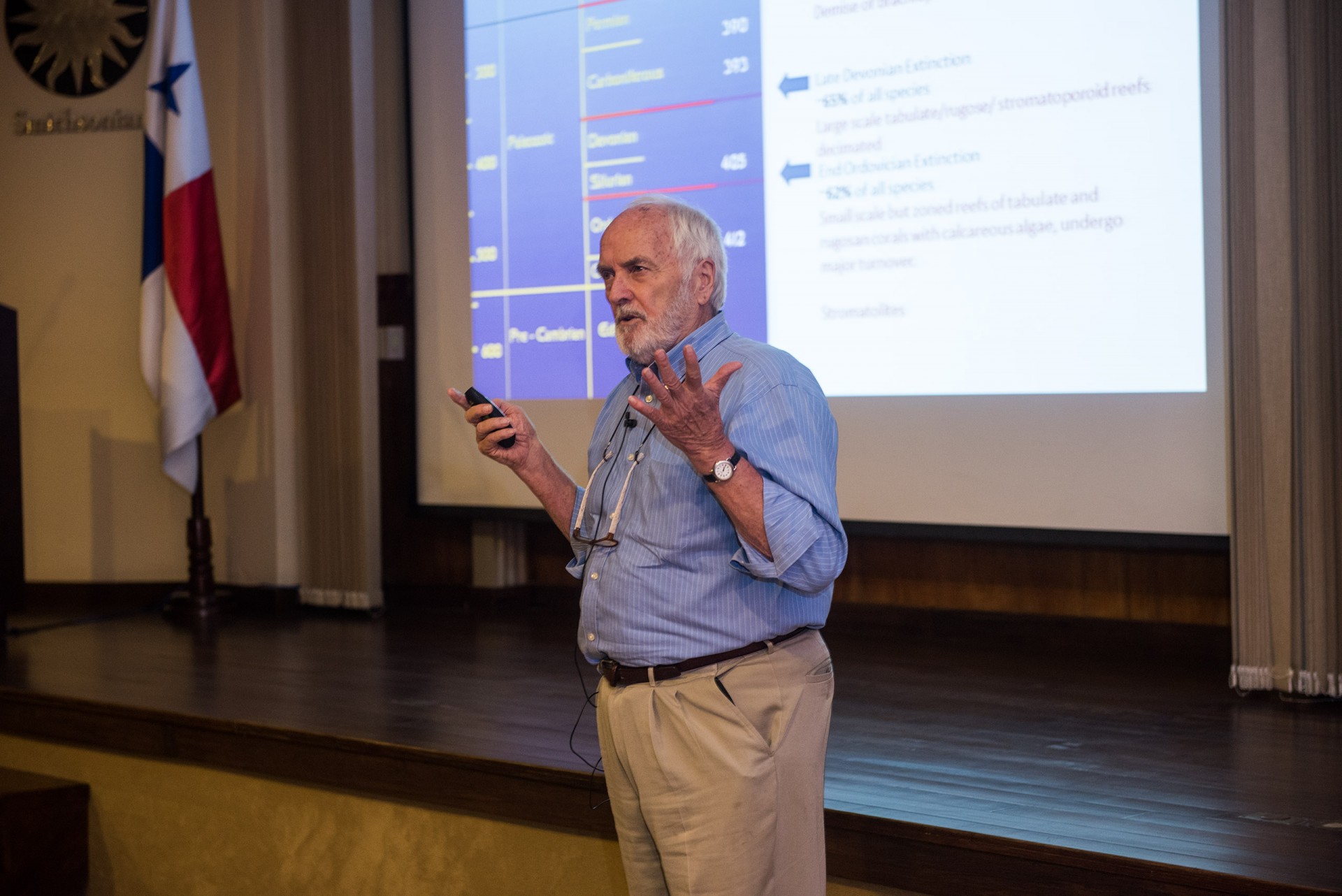

As co-founder of the Panama Paleontology Project with Jeremy Jackson, Tony revealed the geological history of Panama’s Bocas del Toro Province and coordinated the purchase of land for a new research station. Credit: Marcos Guerra, STRI.

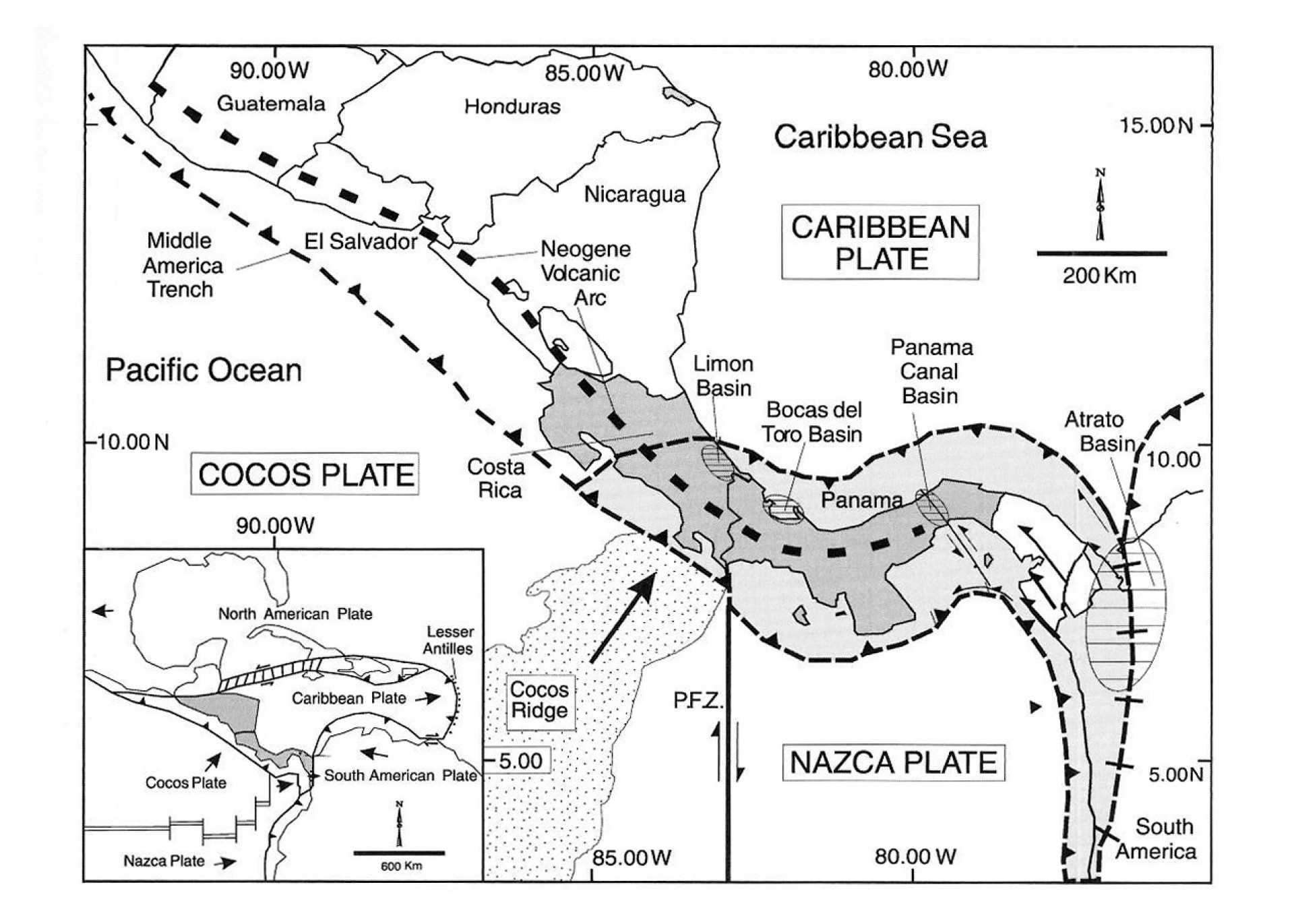

“Map of southern Central America (dark shading) and the Panama microplate (pale shading). Dashed lines with teeth mark zones of convergence; zippered line is Panama-Colombia suture. Very heavy dashed line marks location of Neogene volcanic arc. Fine arrows are Paleogene faults; thick arrows are late Neogene faults. Principal Neogene sedimentary basins located by striped ovals. Spotted pattern defines Cocos Ridge. Arrows on the inset indicate directions of relative motions of the plates.” Figure 1 from Geology of Bocas del Toro Archipelago. Caribbean Journal of Science, Vol. 41 (3).

Staff Scientist Emeritus, Jeremy Jackson. Credit: Marcos Guerra.

By separating the Atlantic from the Pacific, the land bridge redirected ocean currents: the most significant global climate-change event in our hemisphere since the extinction of the dinosaurs sixty million years ago. PPP members published nearly 200 scientific papers in science journals and obtained major grants from the National Science Foundation, the National Geographic Society, the Swiss National Science Foundation, and the Smithsonian Institution.

Tony in the Field

Coates’ most significant scientific contribution during this period was to describe the geological history of Panama’s Bocas del Toro Province.

“Tony converted what was basically a blank, white map of the Bocas del Toro Archipelago, into a map full of colors representing all of the geological formations in the area,” said Aaron O’Dea, who worked on the project as a post-doctoral fellow and is now a staff scientist. “And he knew everybody. We would be walking along a beach or going out to dinner in Bocas Town and someone down the street would yell ‘Hey Tony, Mon.’”

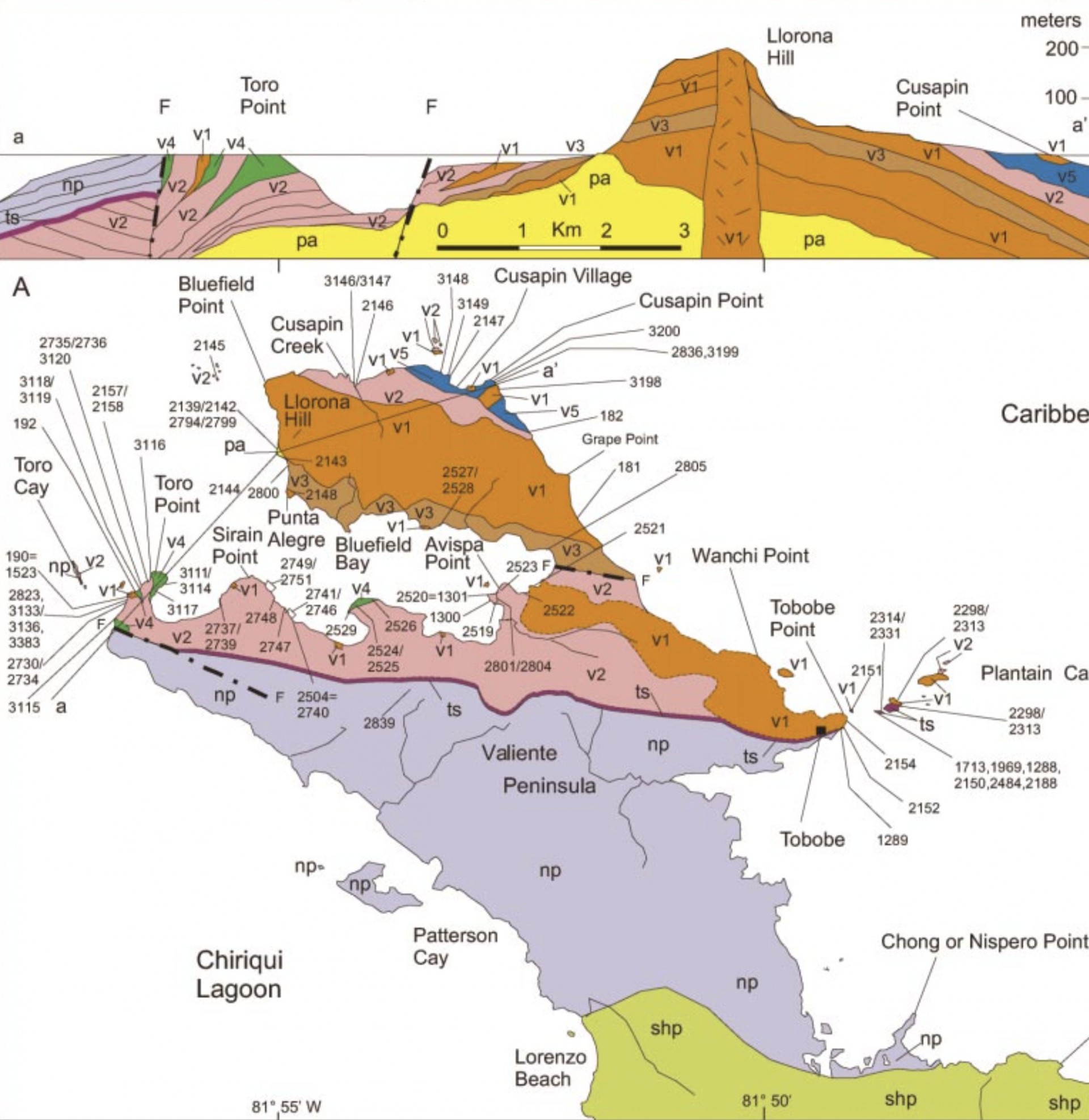

Geology of the Bocas region. Tony layed the lithological foundations so that paleontologists could use the fossil record to document the ecological and evolutionary consequences of the formation of the Isthmus. This is an example how he updated the geology of the region. Credit: Courtesy of Aaron O’Dea.

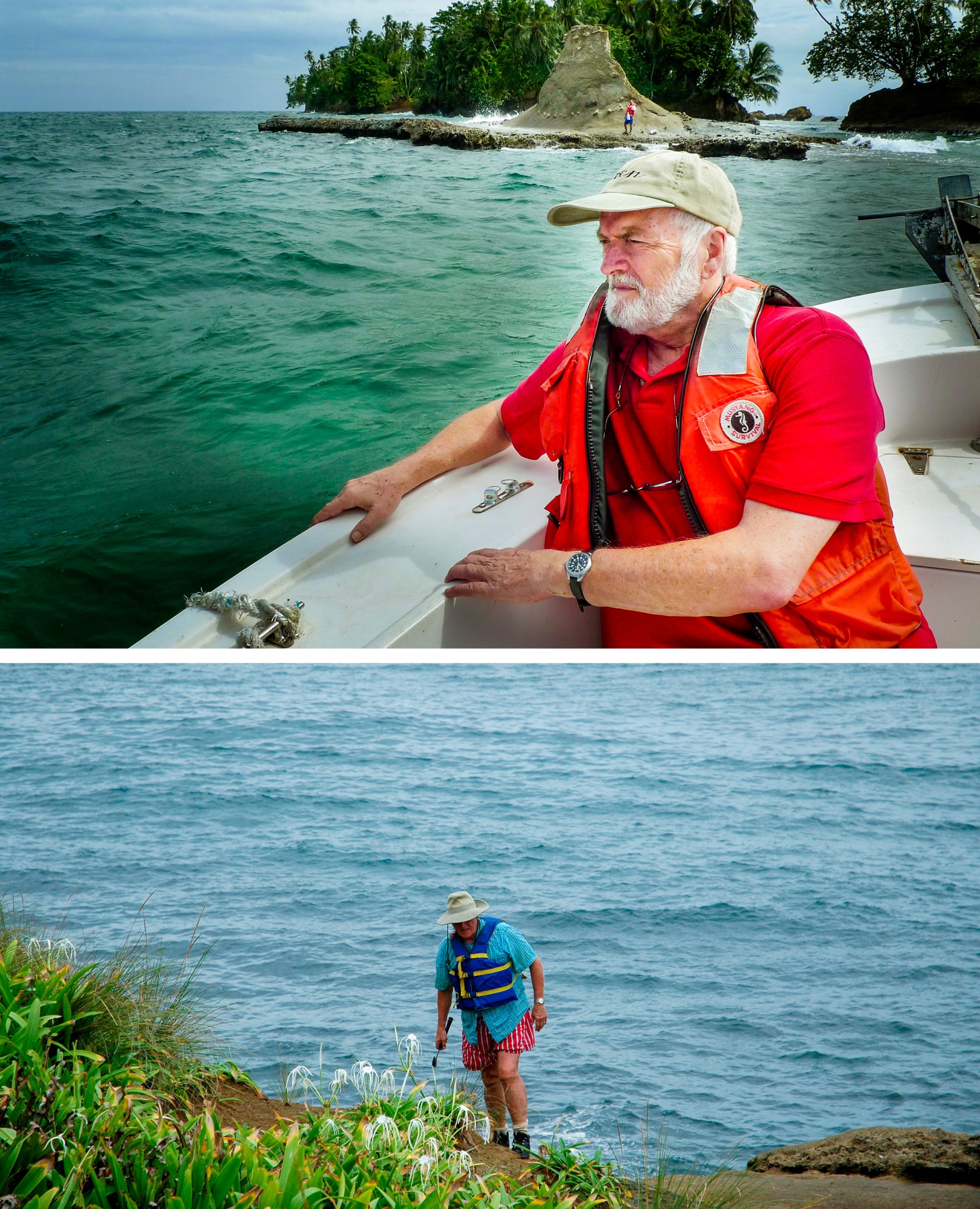

Top: Rock formations in Bocas del Toro reveal the 20-million-year history of the Isthmus of Panama to experienced field geologist, Tony Coates. Bottom: Tony explores a coastal outcrop. Credit: Aaron O’Dea.

One of his favorite people in Bocas was boat driver Sebastian Castillo, who, with Doroteo Machado, maintenance assistant; Gilberto Murray, mechanic; Eric Brown, boat driver, transported Tony and the PPP team to remote coastal outcrops and waited patiently for them as they collected samples for hours in the sun.

Tony was a real field geologist and I do not see these often anymore,” said STRI paleobiologist, Carlos Jaramillo, “Only a field geologist is able to understand what geology is truly about. But not only was he a great scientist, he was also a gentleman. And I don’t see that too often either: A connoisseur of wine history, food, and geography with a great sense of humor. It was always a real pleasure to talk to him.”

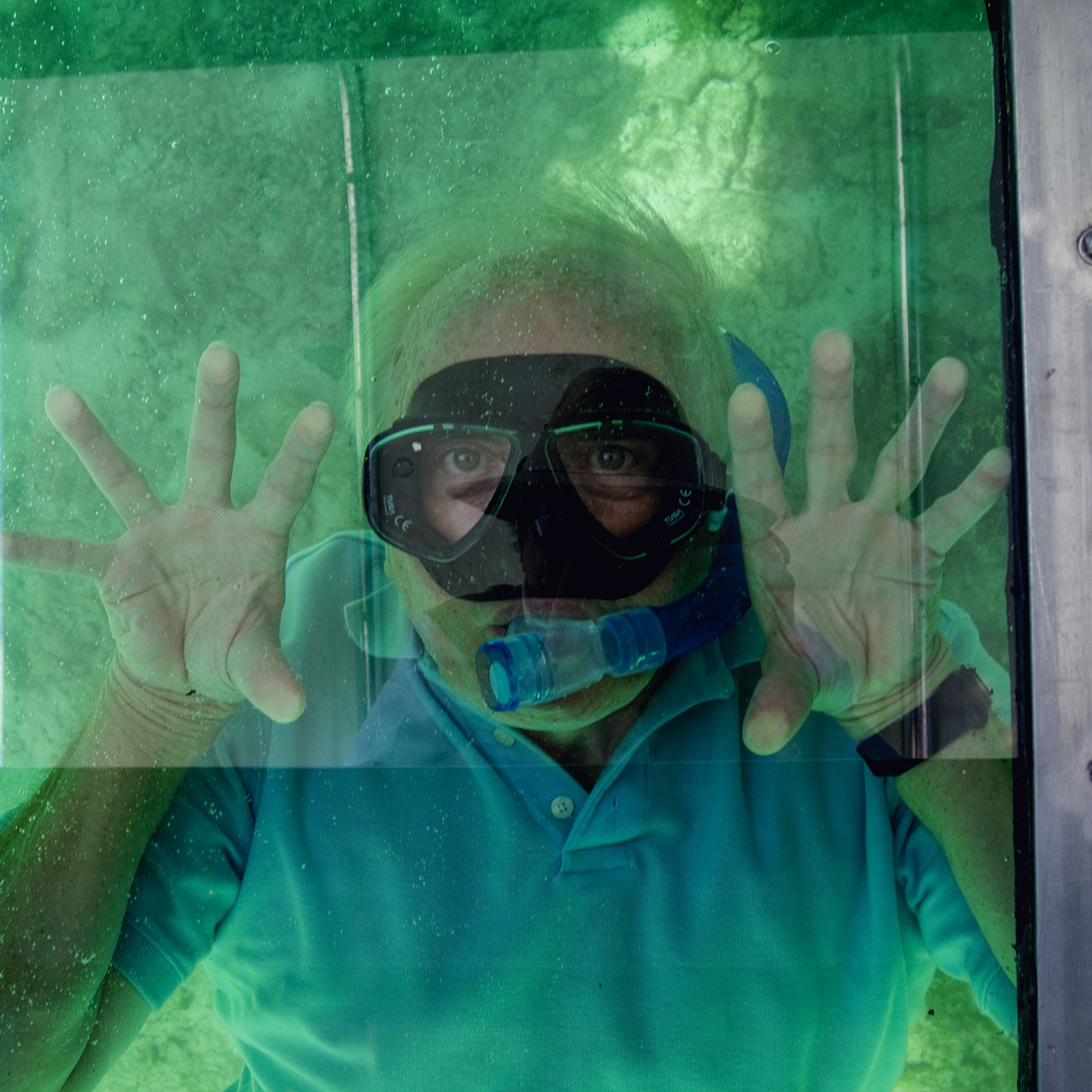

Goofing around: Tony looking up through a glass-bottom boat. Thanks to Tony’s efforts, generous donors were deeply involved in the expansion of the Bocas Research Station and funded the Chair in Paleontology, held by Carlos Jaramillo. Credit: STRI Archives.

Tony as Deputy Director and Science Administrator

Having clearly demonstrated his prowess as a project organizer, Tony accepted the job as Deputy Director of STRI in 1991.

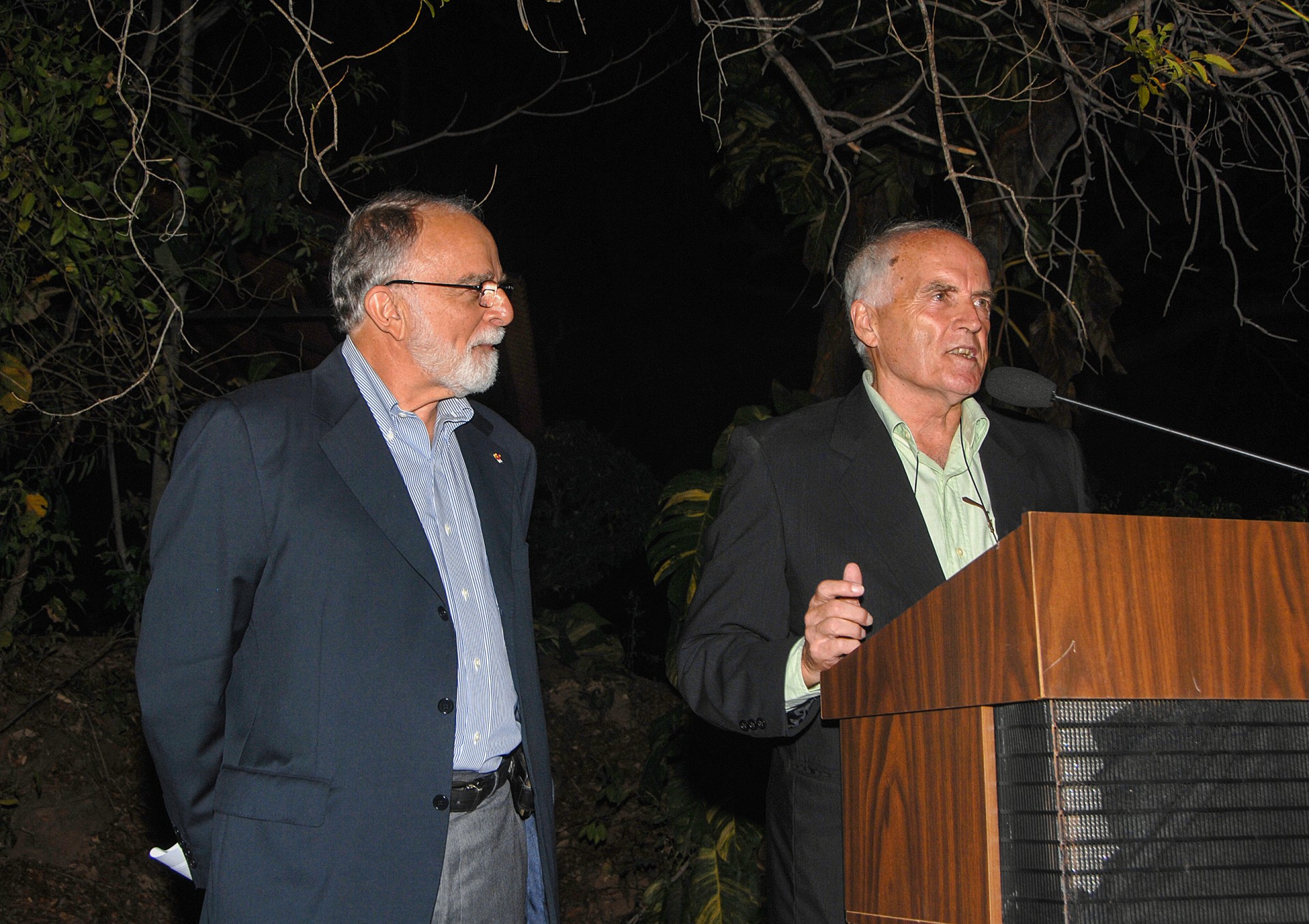

“I remember when I first offered Tony the job of deputy director here at STRI.” Former STRI director, Ira Rubinoff said. “Not surprisingly, when he told his colleagues he was going to accept it, they thought that, in the expression that Tony was famous for, he was “daft.” But Tony knew what he wanted to do. He was going to be able to do research as well as his help administer STRI, and he did an excellent job on both counts.”

Taking it all in stride: Ira Rubinoff, former STRI director, and Tony Coates, former deputy director, probably coming back to the office after smoking cigars in the Tupper Center courtyard. Credit: Jorge Alemán, STRI.

Tony saw the potential for research in other disciplines in Bocas del Toro and was directly involved in negotiating the purchase of land in 1998 for a new research station that would open its doors in 2001. In 2000 he was invited back to Washington as the Smithsonian Institution’s Director of Scientific Research Programs and for the next three years, he was responsible for reorganizing the financing, administration and personnel of all science departments and programs at SI.

Meanwhile, Tony and others on the STRI staff engaged in an in-house sparring match about the timing of the land bridge between continents—extremely important not only to our understanding of natural history, but because a large group of people studying evolution need this date to calculate the rate of genetic change in populations of organisms that were joined or separated by the Isthmus. Colleagues at STRI wrote several papers maintaining that the connection took place much earlier than 3 million years ago. They debated this discrepancy from the halls of STRI’s Center for Paleobiology and Archaeology in Panama to international meetings of the Geological Society of America and on the pages of scientific journals.

Ira Rubinoff and Tony Coates at Ira’s retirement party. Credit: STRI Archives.

Portrait, Anthony C. Coates. Credit: Gian Montufar.

As the debate raged, Tony stuck to the original date, convinced by a lack of evidence of interchange of animals between continents before the 3-million-year mark and the continued mix of genes between marine animals in the Pacific and the Caribbean, suggesting that there was still a way for them to move between oceans. Also, evidence of Pacific deep-water marine organisms in 5-million-year-old formations on the Caribbean side of Panama confirmed the idea that a seaway still existed long after the older date suggested by the opposition. The good-natured tone of the debate kept everyone on their toes and led to new research questions.

Tony as a Teacher

It takes an amazing imagination to picture the world millions of years ago based on scientific evidence consisting of broken rocks and tiny, fossilized marine creatures; and Tony had a special gift for conveying images of a former world to students. Tony’s work inspired a book for 9-10 year olds: A Story in Stone: The Formation of a Tropical Land Bridge, by Tom Gidwitz, published in 2000. For Tony, teachable moments were everywhere and he jumped at the chance to explain the history of the Isthmus to a taxi driver, visiting Princeton students, or VIPs.

Tony explaining the geology of Panama to Integrative Graduate Education and Research Trainees on Barro Colorado Island. Credit: Jorge Alemán, STRI.

At home in the canal town of Gamboa, site of one of STRI’s labs, Tony loved to strike up conversations with students and visiting scientists. At one point, he offered to drive a little white minibus between Gamboa and STRI headquarters in Panama City—shuttling students back and forth and finding out how their research was going. Sometimes, when a student would confide that s/he would be leaving because their fellowship was over but was still in the middle of discovering something interesting, Tony would find a way to support that person for a few more weeks, even if it meant reaching into his own pocket.

Hearing about this, Joyce and Michael Bytnar, donors charmed by Tony’s dedication to students at STRI, gave him a discretionary fund of $10,000 a year earmarked for this purpose.

Tony Coates, consummate field biologist. Credit: Courtesy of Aaron O’Dea.

Tony as Science Ambassador

Tony was well-loved in Panama—an honorary Panamanian. He found ways to involve himself with the local science community: giving talks and participating in seminars and conferences. He edited Central America, A Natural and Cultural History, a marvelous introduction to this part of the world, which was later translated to Spanish as Paseo Pantera.

He served as STRI’s spokesperson to the press on many occasions, one of the most memorable being his interview by Alan Alda for Scientific American Frontiers on PBS (Public Broadcasting Service).

Gloria Jovane, former director of institutional relations at STRI said “I read in one of the many articles that Tony wrote that Darwin could not have designed a better evolutionary experiment than the rise and closing of the Isthmus. Thanks to his scientific contributions toward unearthing the fascinating geology of this area, we can say that the world knows us not only for the Canal and the Panama Papers.”

In 2008, Tony took on the task of Senior Executive Director at the Frank Gehry’ designed BioMuseo in Panama. Not only did he become an important fundraiser and problem-solver, he also worked with Bruce Mau’s team to design the exhibits in what is now an iconic monument to Panama’s biodiversity at the Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal.

Top: Tony hosting the Young Presidents Organization at Panama’s BioMuseo. Bottom: Chief Scientific Consultant and Senior Director at Panama’s BioMuseo, Tony Coates, with executive architect, Patrick Dillon. Credit: Sean Mattson.

Never saying an unkind word about anyone, Tony took his role as a science ambassador quite seriously. His day in the sun came when he hosted the Board of the University of Sharjah and His Highness Sheikh Dr. Sultan bin Muhammad Al Qasimi, Supreme Council Member and Ruler of Sharjah, when they came to visit Panama in 2015. Tony hosted most of STRI’s VIP visitors during this period and he inspired donors to give generously to research here.

“Tony had warm relationships with every major STRI donor, from the Tupper, Hoch, Cofrin, Levinson, Daniels and Johnson families to so many, many others,” said Lisa Barnett, Director of Development. “His enthusiasm and talents for explaining science and the importance of STRI’s work were remarkable, and he was genuinely so fond of everyone that friendships formed naturally.”

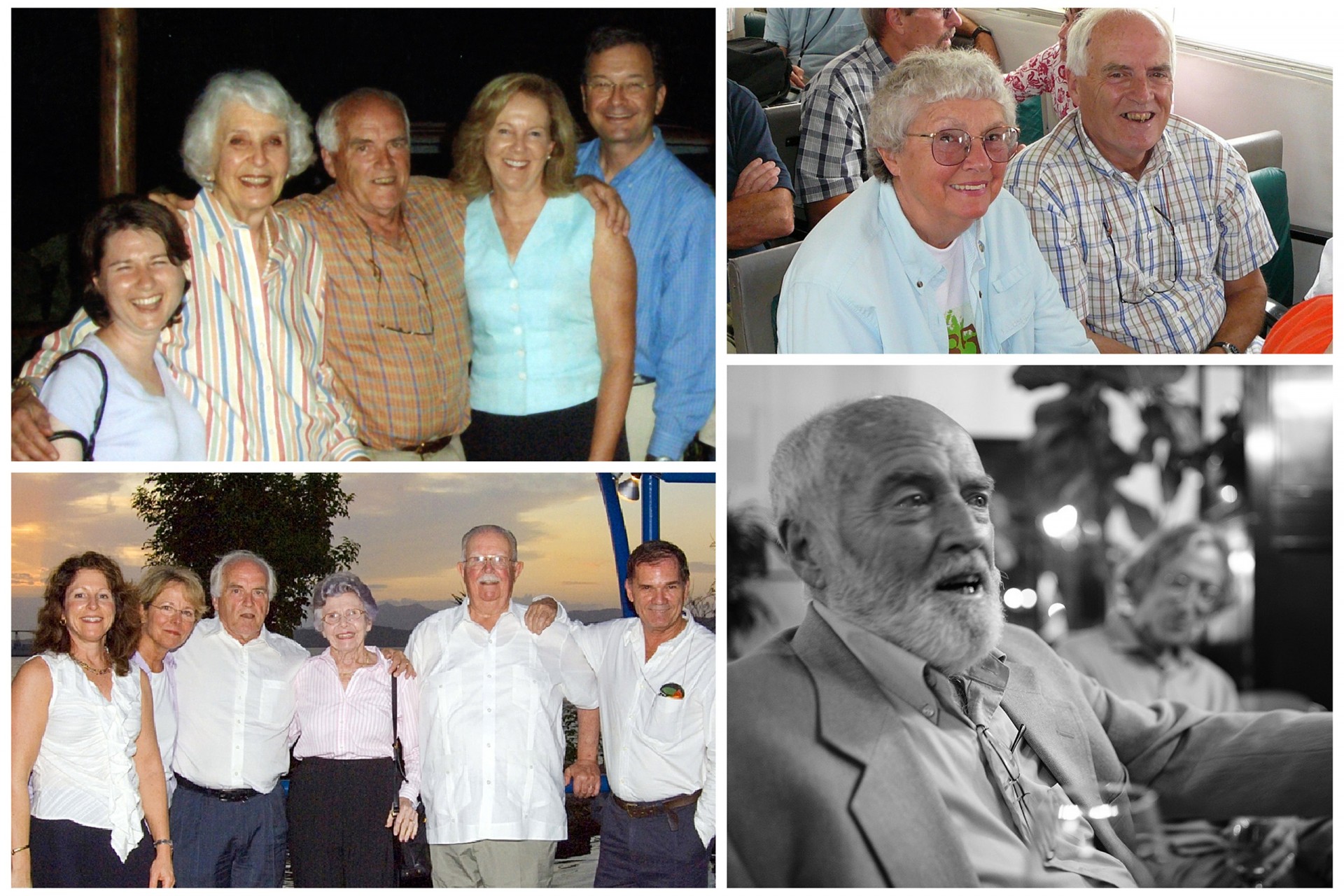

Lisa Barnett, Lisina Hoch, Tony Coates, Jane Hoch and Steven Hoch / With Joan Siedenburg on the boat to Barro Colorado Island Research Station / Mary Ann Cofrin, Edith Cofrin, Tony Coates, Mary Ann Cofrin, David A. Cofrin, Stanley Heckadon / As a natural storyteller, Tony was often the life of the party, entertaining academics and friends alike. Shown here with STRI’s Bill Wcislo. Credit: STRO Archives. B&W photo by Thomas Tupper.

Tony as a Friend

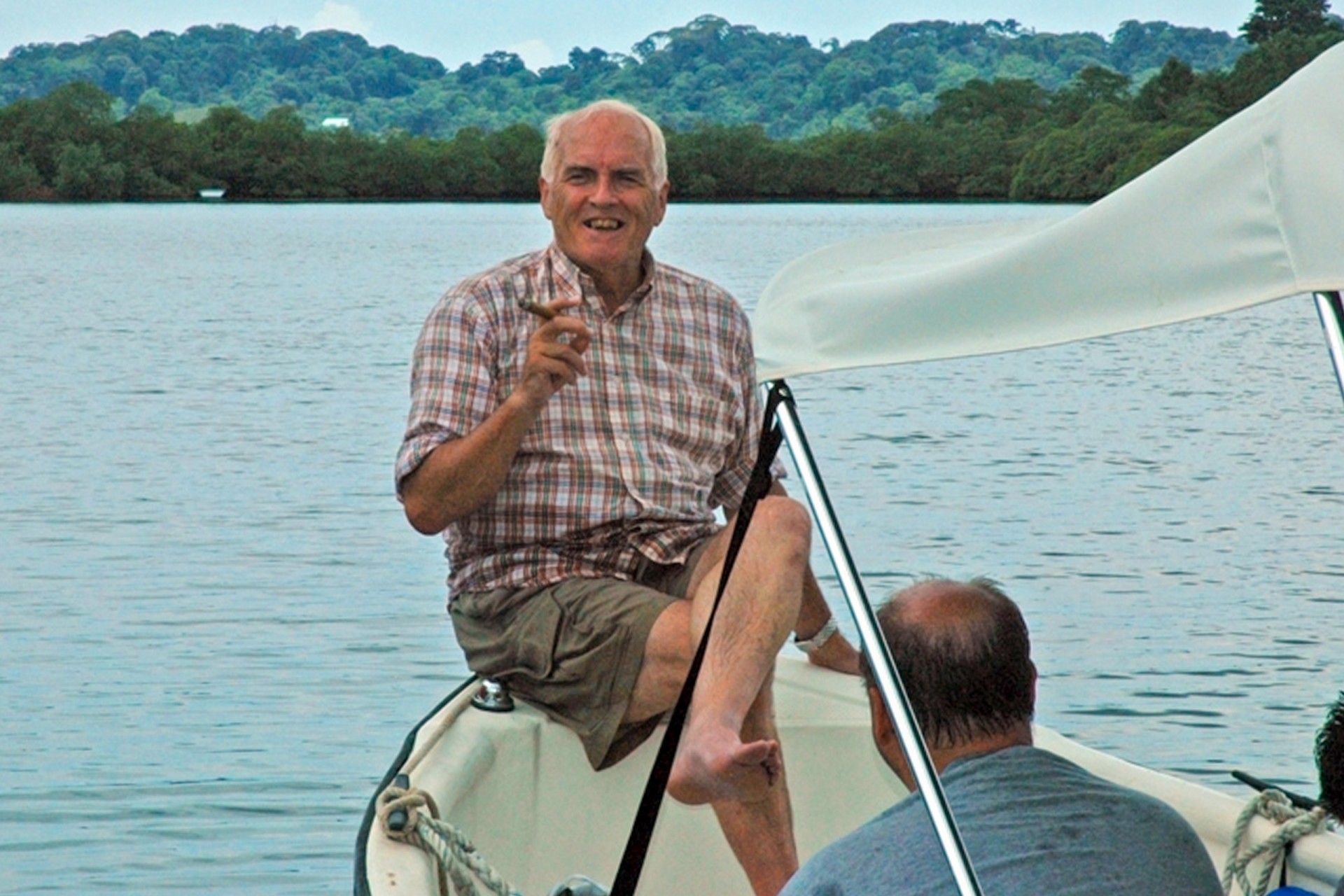

Tony will always be fondly remembered as a friend and a good listener. He loved to smoke a cigar on the breezeway between the Tupper and Tivoli buildings at STRI’s administrative headquarters in Panama City with former STRI director, Ira Rubinoff. And he loved to tell the self-deprecating story about working with his friends Bibi and Lulu in Bocas to build a sailboat—and how they survived the shipwreck when they attempted to sail it across stormy seas.

Tony with Felix Rodriguez and boat driver Sebastian Castillo. Credit: Courtesy of Aaron O’Dea.

Staff Scientist Harilaos Lessios, Tony Coates and Emeritus Staff Scientist John Christy / Tony Coates and Staff Scietist Annette Aiello / On the Jacana: staff scientist Owen McMillan and Tony / Graphic design specialist Jorge Aleman with Tony / Research manager, Milton García with Tony / Staff scientist, Klaus Winter with Tony. Credit: Courtesy of Jorge Alemán.

Tribute to Tony

After retiring to his home in West Virginia with Laure and the dogs, Tony continued to return to Panama from time to time to accompany donor groups.

The last time that Tony came to Panama was in January 2020, when the new dining hall at the Bocas Research Station was given his name, and members of the STRI Advisory Board surprised him with the announcement that a newly endowed, three-year postdoctoral fellowship would be created at STRI in his honor.

Invaluable scientific support: Plinio Gondola, BRS scientific coordinator; Sebastián Castillo, boat driver; Tony Coates; Doroteo Machado, maintenance assistant; Gilberto Murray, mechanic; Eric Brown, boat driver. Credit: Jorge Alemán, STRI.

In a short video created for the event, Aaron O’Dea said: “What a great storyteller you are, Tony. And you know, I think it's truly fantastic and fitting that a building that's designed to foster those kinds of social interactions and collaborations for the next generation is going to bear your name.”

In 2020, friends of STRI also joined together to create an endowment for a fellowship in Tony’s honor.