Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Forest

Caretakers

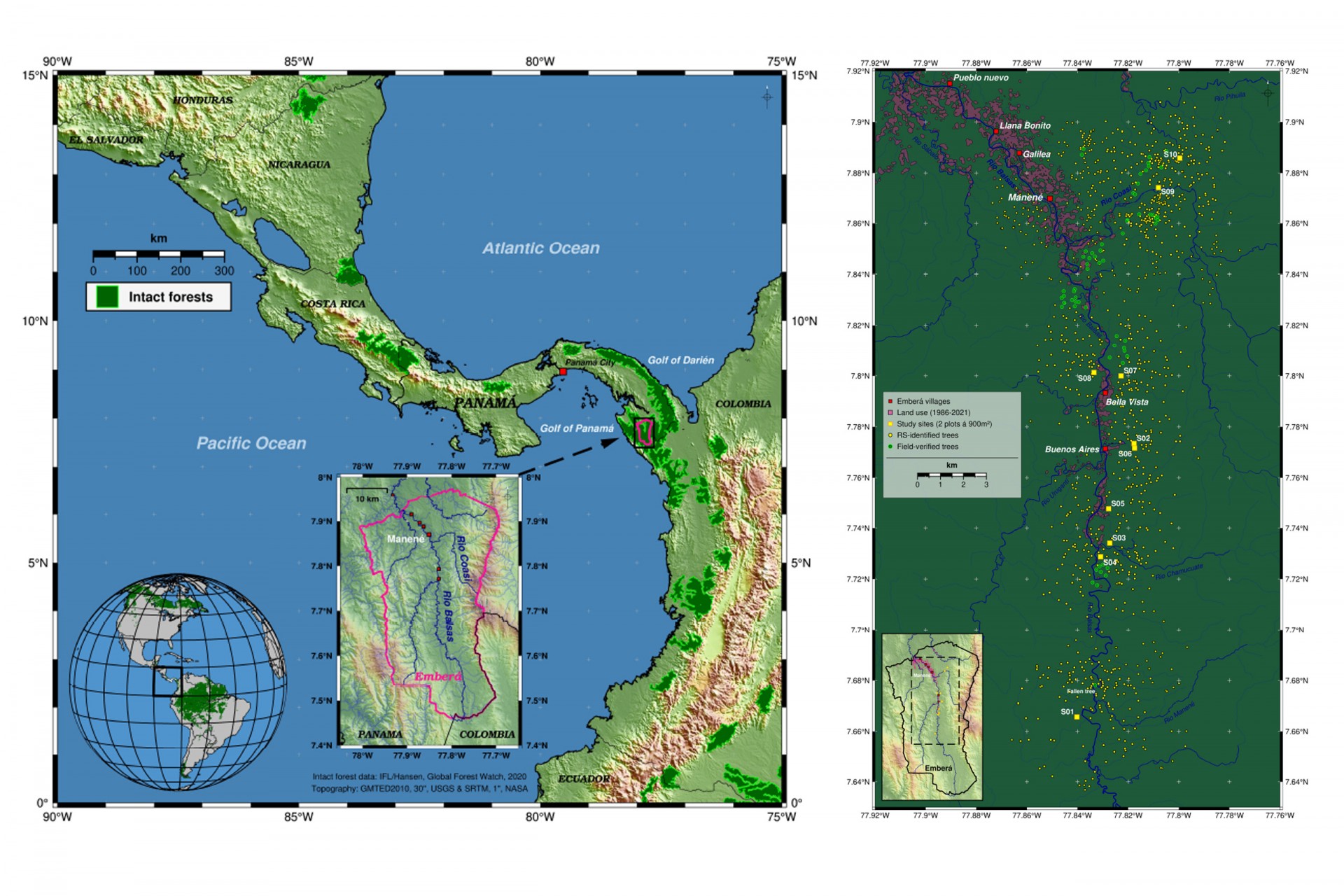

Bacurú Drõa: How well do Emberá indigenous communities conserve old growth forests in Darien, Panamá?

Text by: Beth King

Existing conservation policies rarely reward local people who care for old-growth forests. In this study, Indigenous Emberá residents worked with scientists to show how, through their sustainable lifestyle in communities established during the 1960’s-1980’s in one of Central America’s most pristine, old-growth forests, they act as custodians, conserving this, shared space.

The Balsas River flows down from hills marking Panama’s Colombian border, draining the spectacular, pristine forests of the Darien Gap—the only breach in the Pan-American Highway’s span from Alaska to Argentina. Smithsonian researchers and colleagues joined members of six Indigenous communities to document their successful custodianship of a forest dominated by ancient, gigantic trees.

“Old-growth forests are disappearing all over the world,” said Catherine Potvin, STRI research associate and professor at Canada’s McGill University, “yet they are the cradle of biodiversity, and hold enormous carbon stocks. Our occidental economy has failed to find ways to reward the Indigenous people that have cared for them from times immemorial. With Bacuru Droa, I hope to provide a blueprint of how engaging with science can improve the livelihoods of Indigenous forest-caretakers under pressure to join cash economies.”

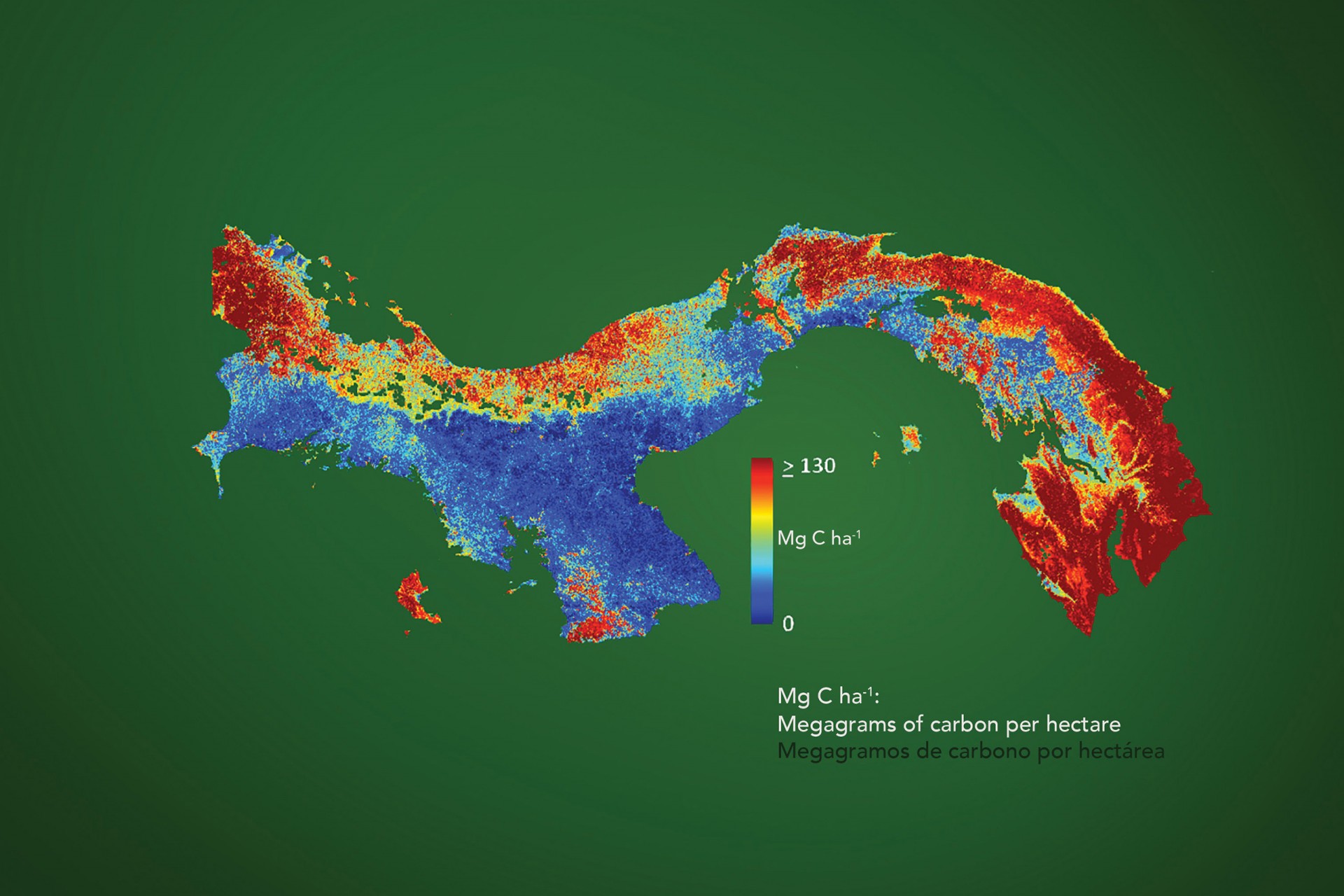

Tropical forests store more than half of all terrestrial carbon in their wood and leaves. When people cut trees, rotting timber releases carbon back into the atmosphere, where it contributes to global warming by trapping the sun’s heat close to the Earth. Almost 40% of all natural lands comprise Indigenous territories, home to roughly 80% of all species living on land. As humanity copes with a climate crisis and the sixth great extinction caused by our voracious consumption of fossil fuels and natural resources, Indigenous peoples’ immediate land- and resource-use decisions directly affect our survival.

Before the Spanish first arrived in Panama 500 years ago, Indigenous people lived in small family groups along the great river systems that drain Panama’s Darien Province and the neighboring Colombian Chocó. In 1980, Panama’s president created Darién National Park without due consultation with Emberá residents, whose communities were subsumed by the park. In 1981, the United Nations recognized the park as a World Heritage Site based, in part, on the presence of flora and fauna considered to be unique to the site or endangered. The land rights of Indigenous residents, members of the Tierras Colectivas de Rio Balsas, have never been formally clarified. Some Emberá have also expressed their frustration that of a $10 million debt-for-nature swap between the U.S. and Panamanian Government, 2004 to protect Darien National Park, they were not compensated for their role as forest caretakers.

The Balsas river communities were founded between 1962 (Manené) and 1980 (Pueblo Nuevo). Because no roads access the area, forest ecologist Catherine Potvin was one of very few foreigners to regularly visit the community of Manené since she travelled upriver, a 13-18-hour dugout journey from the nearest port, to meet one of her student’s grandfathers, a respected elder and spiritual guide (jaibaná) over 25 years ago. She is currently working with the communities to document the history of land use in the area. The local coordinator of the resulting project, Alexis Ortega, expresses the communities’ intention as an attempt to “prove to the world that they have forever conserved the forest.”

Together the intercultural group confirmed the hypothesis that the traditional presence of the Emberá on the land is compatible with the presence of intact, primary forests.

These maps show intact forests in dark green. Source: Global Forest Watch.

They asked three questions: 1) Has the vegetation in the area changed significantly since their communities were founded; 2) Has their “footprint”, the impact of their communities on the land, changed; and 3) What is the current composition of the forests now and what would conserving them in the future involve?

Emeritus staff scientist, Dolores Piperno is an expert on tropical phytoliths, tiny plant microfossils deposited when water containing the mineral silica flows through plant cells. These glassy structures remain in soil after plants rot. By comparing shapes of phytoliths from soil samples taken at different depths with phytoliths in a reference collection of phytoliths from 2300 species of modern plants, Piperno and her team discover which plant species were common hundreds, and even thousands of years ago.

Her group at the STRI Center for Tropical Paleobiology and Archaeology in Panama City analyzed soil cores from 10 locations at 8 forested sites in the Balsas River area to discover which species of plants grew there in the past. Nearly all the phytoliths were from forest tree species. They also looked for charcoal in the samples but found very little evidence of forest fires or intentional burns. The only strong evidence of human intervention at the forested sites was the prevalence of palm phytoliths.

For hundreds of years, Emberá walking in the forest enriched the presence of palms like the Trupa (Oenocarpus mapora) by pushing exposed seeds down into the soil, resulting in groves of these palms. They mash Trupa wood and collect palm oil, used to fry food.

"Our phytolith and charcoal results indicate Indigenous peoples in the Darien used the forests sustainably for thousands of years, maintaining their high diversity and structure,” Piperno said. “Similar results have come from regions in Amazonia.”

To better understand how the footprint—the area affected by the Emberá—has changed, Manené community elder, Manuél Ortega, began by creating a hand-drawn map of the upper Balsas and marked important cultural sites and landscape features such as rivers, former family settlements and current villages. Residents call the map Dai Ejua, “our territory”. Then the team visited these spots, marking their GPS locations on a contemporary map.

This impressive Ceiba tree fell across the river. Its height from base to top at 60 meters (197 feet), once again confirming the presence of unusually tall trees in the area.

After a search of NASA/USGS Landsat satellite images of the area taken between 1986 and 2021, researchers compared bare soil exposed during the period 1986 to 2000 with the area exposed from 2013 to 2021 and calculated that Emberá settlements only affected about 1.3 percent of the entire territory, a very small footprint that remained stable during the last 35 years.

In each of the six communities, most development is concentrated along the river’s edge where houses, animal pens, plantain groves and gardens are located. Within 1 km from the river, in wetter forests, the Emberá raise pigs and cultivate wild plants for medicine and other domestic uses. Further back from the river in second growth forests, they harvest a limited number of trees for timber.

At the same locations where the soil samples were collected, teams of Embera technicians and scientists used terrestrial laser scanners to image the 3D structure of the forest, taking care to include the biggest trees to estimate maximum tree heights and tree diameters. They were surprised to find many larger trees per hectare than in many other areas. The tallest towered more than 65 meters (185 feet) above the ground. The largest trees hold a disproportionately large amount of all forest carbon, but they are hard to study because they are usually so far apart and so long-lived.

The maximum height of one species (Faramea occidentalis) was recorded as 10 meters in the forests at the Smithsonian research station on Barro Colorado Island in central Panama. In the forest plots in the Balsas River watershed, researchers measured 55 trees greater than 10 meters in height and 8 trees taller than 20 meters—twice the reported maximum height!

The first-ever national carbon stock survey by LiDAR in the world, in 2013, recognized Panama’s Darien Province as the area of the country with the highest carbon stocks. (Asner et al image)

While exploring the area upriver, the team came across an enormous, fallen Ceiba pentandra tree. The height of the fallen tree was estimated to be greater than 60 meters and its diameter above the buttress measured 2.7 meters. Later, they could see the crown of the tree in satellite images taken before it fell, and the space it left—and concluded that it fell sometime during the rainy season in 2018.

"When we discovered the fallen tree over the Balsas river, everybody in the team was in awe,” said co-author Mattias Kunz, “Its sheer size and diameterwas amazing! There we stood, all 20 members of the technical team, with room for many more. Using remote sensing we were able to locate many other tree giants confirming that they are actually common in the Balsas area."

Based on their findings, the team proposes three actions: First, to ask international policy makers to reconsider policy that make old forests “essentially invisible” from the standpoint of climate-based mitigation. Unmanaged forested lands that remain forested are currently excluded from national forest carbon inventories. 2) include forest conservation initiatives in calculating carbon stocks and 3) recognize indigenous land rights.

The authors of this paper conclude:

“Thirty years after the negotiations of the Kyoto Protocol that de facto excluded standing forests from the climate mitigation toolbox… the time has come to generate a sustainable stream of income to jurisdictions such as indigenous territories, in exchange for their continued commitment to protecting the forests as they have done in the past, according to traditional norms.”