Marine resource use has influenced human population on the Central American Isthmus for millennia

Flowers from

Darkness

“Tropical forests are the result of an

accident of history.” - Carlos Jaramillo.

About 66 million years ago, a radical change on the Earth filled tropical forests with flowers. A new catalog of fossil pollen grains may hold an explanation.

Almost no flowers bloomed in tropical forests 145 million years ago. Plants reproduced by means of spores wafted on the wind and seeds sprinkled from cones rather than borne in fruit. Ferns and giant gymnosperms—related to pines, Ginkos and cycads—cast their shadows over dinosaur trails.

What happened since then to transform this nearly flowerless world into rainforests as we know them today: towering trees dotted with yellow, purple and pink blossoms and draped with orchids and clearings choked with passion flower vines?

STRI staff scientist Jaramillo thinks a major force of change behind the transformation of tropical forests was the Chicxulub impactor—a huge comet slamming into what is now Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula 66 million years ago. The impactor vaporized soil and rock to create a crater about 150 kilometers (more than 90 miles) in diameter and 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) deep.

The impact triggered an immense burst of thermal energy and a 1000 km (600 mile) per hour blast of wind followed by a firestorm. Compared to the explosion of Krakatoa in 1883, which sent a cloud of dust around the planet so dark that people in New York called fire departments to report a massive fire on the horizon, three hours after the Chicxulub impact, the entire planet was plunged into deep darkness, a sudden blackout for 6-9 months, followed by decades of half of the normal amount of light.

Each rock sample yields a slide full of microscopic, fossilized pollen grains from ancient flowers.

Average temperatures in the tropics dropped from about 27 degrees Celsius before the impact to 5 degrees Celsius after. It is estimated that it took the climate about 30 years to recover.

Jaramillo thinks that the dark and the cold, or the ashes raining down—something about the impact—not only ended the reign of the dinosaurs, it gave rise to the reign of flowers.

Perhaps in the darkness, desperate insects navigated through the air, following trails of musky perfume to find pollen to carry from one tiny flower to the next.

Perhaps plants offered starving flies, the descendants of carrion flies who had feasted on the rotting corpses of dinosaurs after the impact, corpse-scented flowers with tiny nutrient rewards.

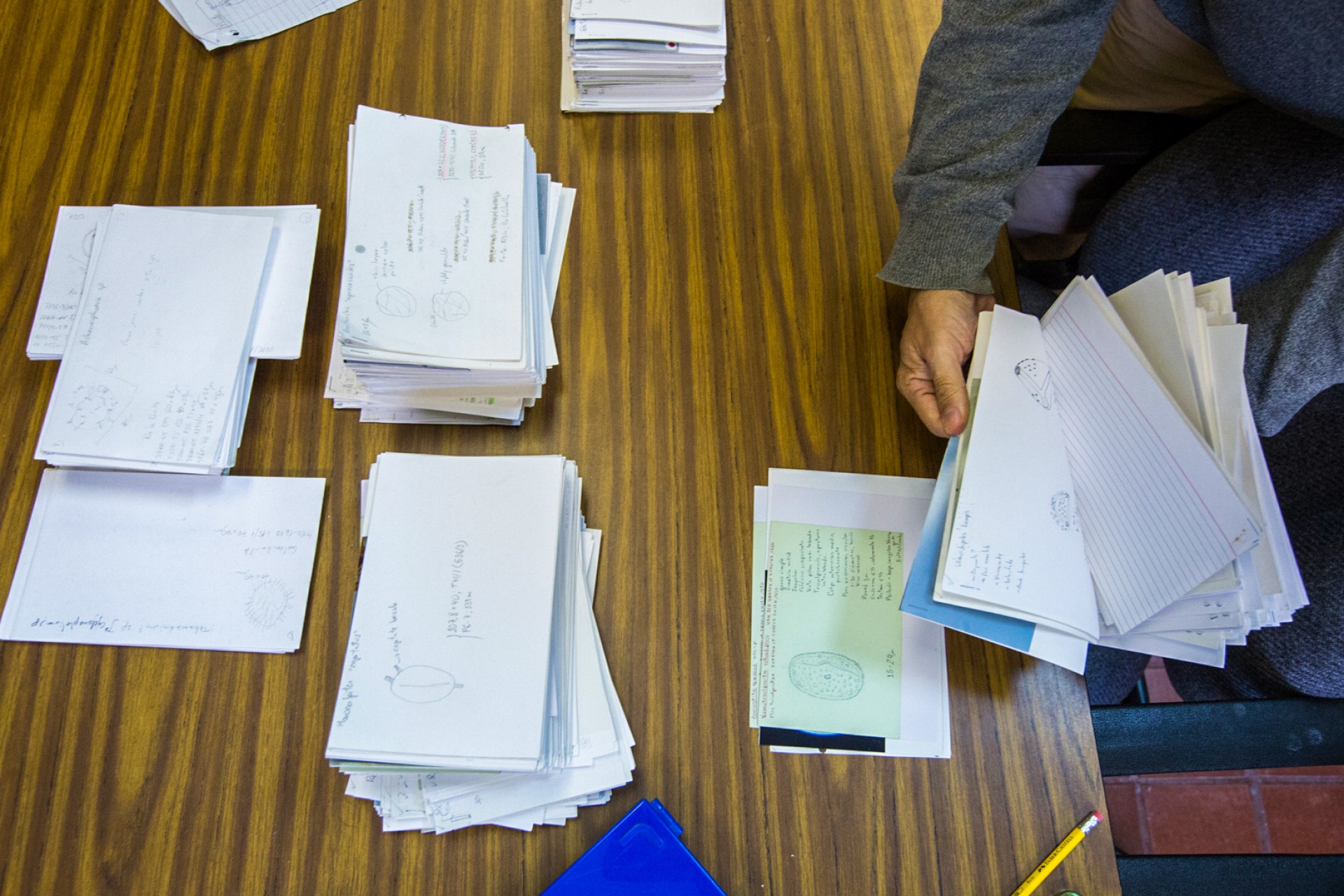

Jaramillo describes each pollen grain based on up to 70 different characteristics. Is it brown or black, bumpy, smooth or pitted?

How to see into that dark past? Jaramillo depends on the tiniest pollen grains trapped in rocks from the onset of the Cretaceous period, 150 million years ago, when flowering plants first appeared on earth to the beginning of the Paleogene Period, 65 million years ago, when they suddenly took over the canopy of the tropical forests. He has already worked for almost 15 years to classify pollen from 65 million years ago to the present and now he will go back to the time before the impact occurred.

The tropics makes life difficult for geologists. They search out places where a stream has drilled down into the earth, exposing layers of rock. Or they purify the pollen from the long tubes or cores of rock brought up by oil-drilling rigs.

Jaramillo and his team retrieved rock samples from 17 sites across the Americas, each covering a slightly different part of this time period. From each of 1300 samples, he separated out about 300 pollen grains. That makes about 390,000 individual pollen grains to identify!

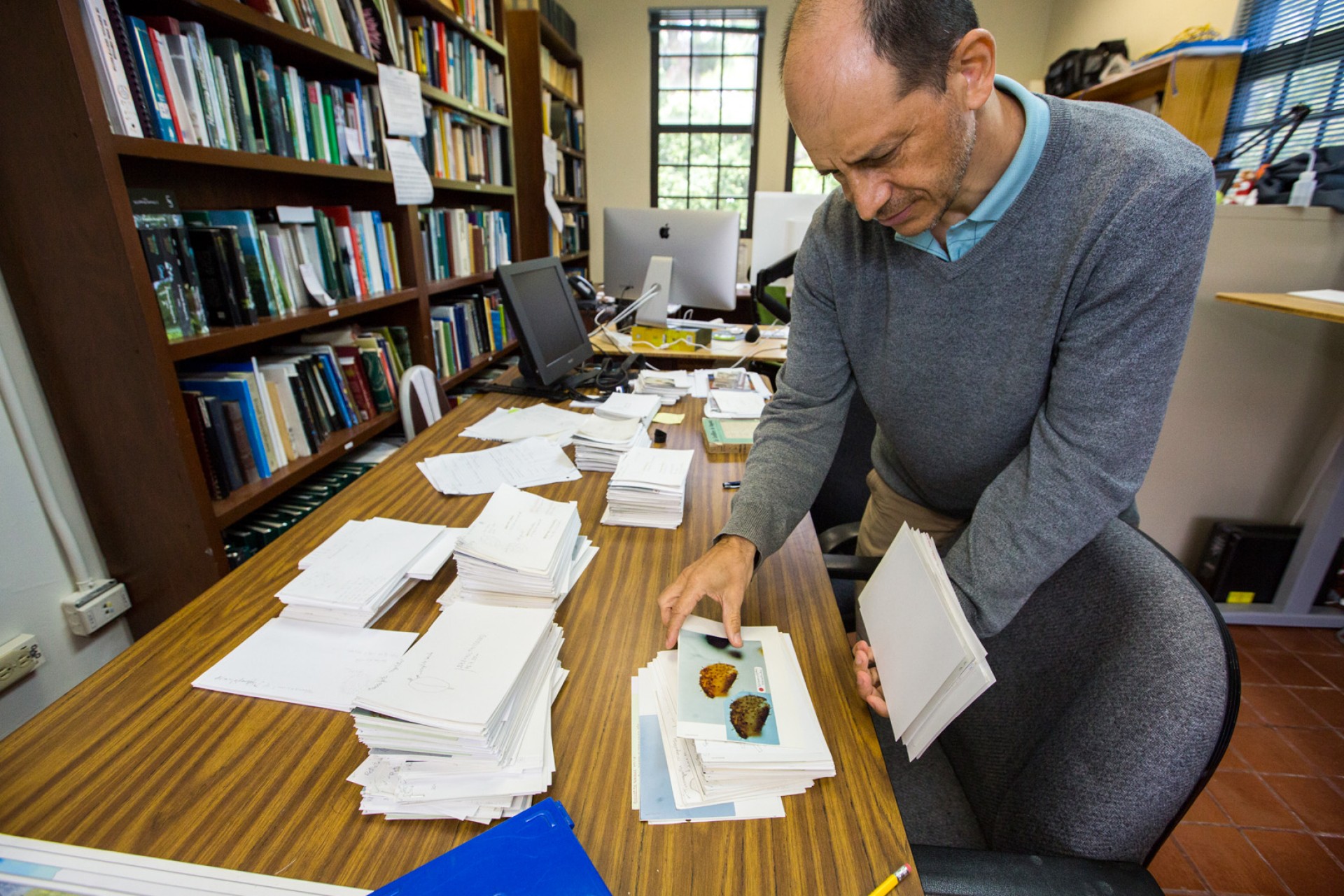

Piles of 5” x 8” index cards cover the long table at the center of his tall-windowed office on Ancon Hill in Panama. Each card represents a unique species: pencil drawings, notes and an occasional photo of some microscopic feature paper-clipped to the back. He uses 70-some characteristics to classify each grain. Is it smooth or bumpy, round or oblong, honey colored, brown or black? Does it have an opening? Is it ornamented, bearing long spines or blunt-tipped protrusions?

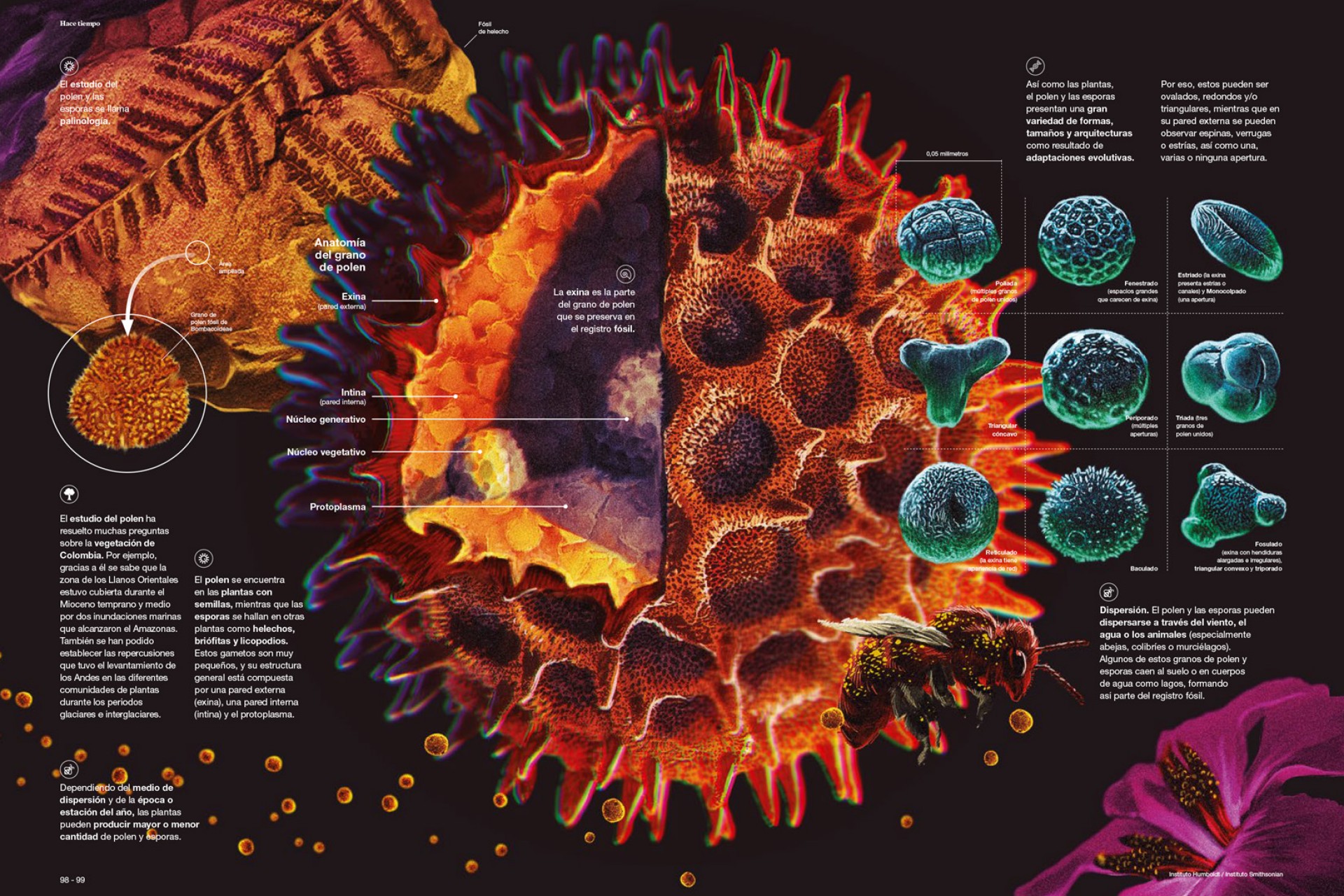

Graphic artists at the PuntoAparte publishing house in Colombia illustrated examples of pollen grains for a new book, Hace Tiempo, co-authored by Jaramillo and colleagues, and available free online (see news story).

About 80 percent of the pollen grains he finds have never been described before and represent a new species. “This kind of natural history cataloging was done to characterize the pollen of European flora a century ago,” says Jaramillo. “Now no one there does this kind of work. In South America, we had to start from almost nothing. But if I don’t do it, it isn’t going to be done.” His work will result in a massive monograph on the pollen of the tropical forest before and after the impact: more than 1000 species.

He’s been working on this part of the project for more than 5 years. “It’s time to finish. I’m ready to finish,” he says as he pauses to go over to his desk to answer an incoming chat—house repairs.

Each card on the table represents a unique type of pollen from ancient plants. While many have modern relatives, most are likely to be new to science.

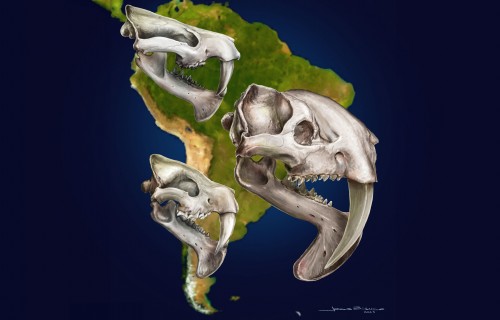

So far, only the general conclusions are certain: The forest after the impact was nothing like the forest before the impact. Before the impact it was just one big, warm world, on average about 7 degrees Celsius warmer (about 12 degrees Fahrenheit) than today with a strong greenhouse effect caused by about 1000 parts per million carbon dioxide. Before the impact, the forest canopy was open, dominated by gymnosperms [Non-flowering plants].

When the curtain rose after the long, cold night, trees took on the broccoli-shape they have today, the angiosperm-dominated canopy closed, dividing the hot, brightly-lit outer edge of the forest from a dark interior. And the pollen also changes completely.

The monograph (a document treating a single subject) on pollen from ancient tropical forests, will probably include more than 1000 descriptions of different pollen types.

“It was a completely different world,” Jaramillo says. “Nearly all the plants from before the impact were extinct after it. Also, there were few significant differences between forests in North America and South America, the latitudinal gradient that we see today between forests in the North and South didn’t exist, it seems to be related to the presence of plants with flowers.”

“People used to think that the first flowers were like the Magnolias, but now we think they were tiny, perhaps aquatic, with tiny petals, probably dispersed by insects. And it wasn’t as if the flowering plants were just more competitive and outcompeted the gymnosperms, slowly replacing them over time. That wasn’t what happened. Perhaps the angiosperms [flowering plants] had an advantage because they were used to growing in frequently disturbed habitats, they were the first to colonize after disturbances. And then, once the angiosperms made it up into the canopy, the game was over. There was no way that the gymnosperms could compete with them. They grow too fast.”