Pseudoscorpions: Little guardians of crevices (public talk in Spanish)

A Fearless

jewel

NOT a Bird Dropping

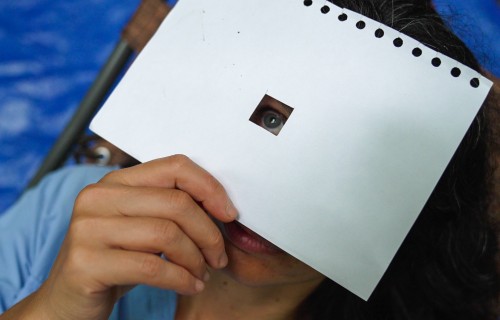

The discerning eye of staff scientist, Annette Aiello, observed the fearless behavior of an iridescent insect resembling a bird dropping containing embedded, blue seeds.

The first time she glanced at a bluish bit of gunk on a leaf in her garden in Arraiján, Panama, Annette Aiello thought it was a bird dropping, but her training as an entomologist led her to look again. After years studying butterflies as they transition from eggs to caterpillars to adults, she “was duped into thinking it was a caterpillar.”

Leaf-eating caterpillars often imitate bird droppings to disgust potential predators. But, as Annette prepared to collect the leaf, the “caterpillar” rolled off onto the ground, where she spent 20 minutes searching for it in vain. Frustrated, she kept checking the low, spiny tree called Xylosma chlorantha, for more.

The scientific name of the tree comes from the Greek words xylon (wood) and osme (smell)—and its leaves may be producing some nasty chemicals to keep most insects from eating it. Extracts of a closely related plant in India are used as an antispasmotic, narcotic and sedative. Other members of the same plant family (Salicaceae) produce the active ingredient in aspirin, salicylic acid.

Days later, Annette’s patience was rewarded. This time she was ready, catching the second specimen in a plastic bag. To her surprise, rather than a caterpillar, the bag contained a jewel beetle. Many jewel beetles (Buprestidae) are prized by insect collectors for their iridescent wings and even made into jewelry, but this species, Amorphosoma penicillatum, was the first jewel beetle Annette had seen that looked like a piece of excrement.

Xylosmoa chlorantha trunk with branched spines.

And true to form, when she poked and prodded the beetle, rather than flying away, which is what most other jewel beetles would do at the earliest sign of human approach, it stayed very still—as still as a bird dropping: a fearless bird dropping.

Beetles have been around since the Carboniferous period of Earth’s history about 350 million years ago. And about half of all beetles are plant eaters. Long ago they gained the ability to produce special enzymes that degrade plant cell walls, the most abundant source of carbohydrates on the planet. One of the explanations for the fact that there are so many species of beetles on Earth (more than 400,000) is that many beetles are specially adapted to live on a single plant species.

“The ‘What me worry’ attitude of A. penicillatum is puzzling,” Annette writes in the Coleopterists Bulletin, “Yes, it is an amazing mimic, which undoubtedly helps protect it from attack by birds. Nevertheless, once captured, why does this beetle not attempt to escape? Does it have a chemical defense that we failed to detect? Is it such a hard object that a bird decides to reject it? There are a few reports of other jewel beetles that look like excrement, but nothing about their behavior was described, so we have no additional clues to explain this surprising discovery.”

“Possibly, fearless behavior occurs elsewhere among the more than 14,700 species that comprise the Buprestidae worldwide,” Aiello said, “but in the case of such rare beetle species, these questions are unlikely to receive answers anytime soon.”

Reference: Aiello, A. 2019. Amorphosoma penicillatum (Klug, 1827) (Coleoptera: Buprestidae: Agrilinae): A Fearless Jewel Beetle in Panama. The Coleopterists Bulletin, 73(4):1-3 https://doi.org/10.1649/0010-065X-73.4.1102

For more about Annette’s entomological exploits, check out our article, Females in Flatland, on the Smithsonian Voices blog.