For the first time since records began,

the cold, nutrient-rich waters of the

Gulf of Panama failed to emerge

Dodging

Olive ridley turtles avoid

unfavorable conditions

Tropical Eastern Pacific

Cover illustration by David Serracchiani

The nomadic nature of these marine turtles allows them to adapt to dynamic environmental factors, but presents a conservation challenge that STRI researchers hope to resolve

In the Eastern Tropical Pacific —including the coastal waters of Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia and Ecuador—bycatch of sea turtles is among the highest on the planet. Sea turtles cross through fisheries as they migrate from breeding grounds to foraging areas. Marine ecologists at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama studied the turtles’ migratory routes and what influences them in hopes of improving conservation policy.

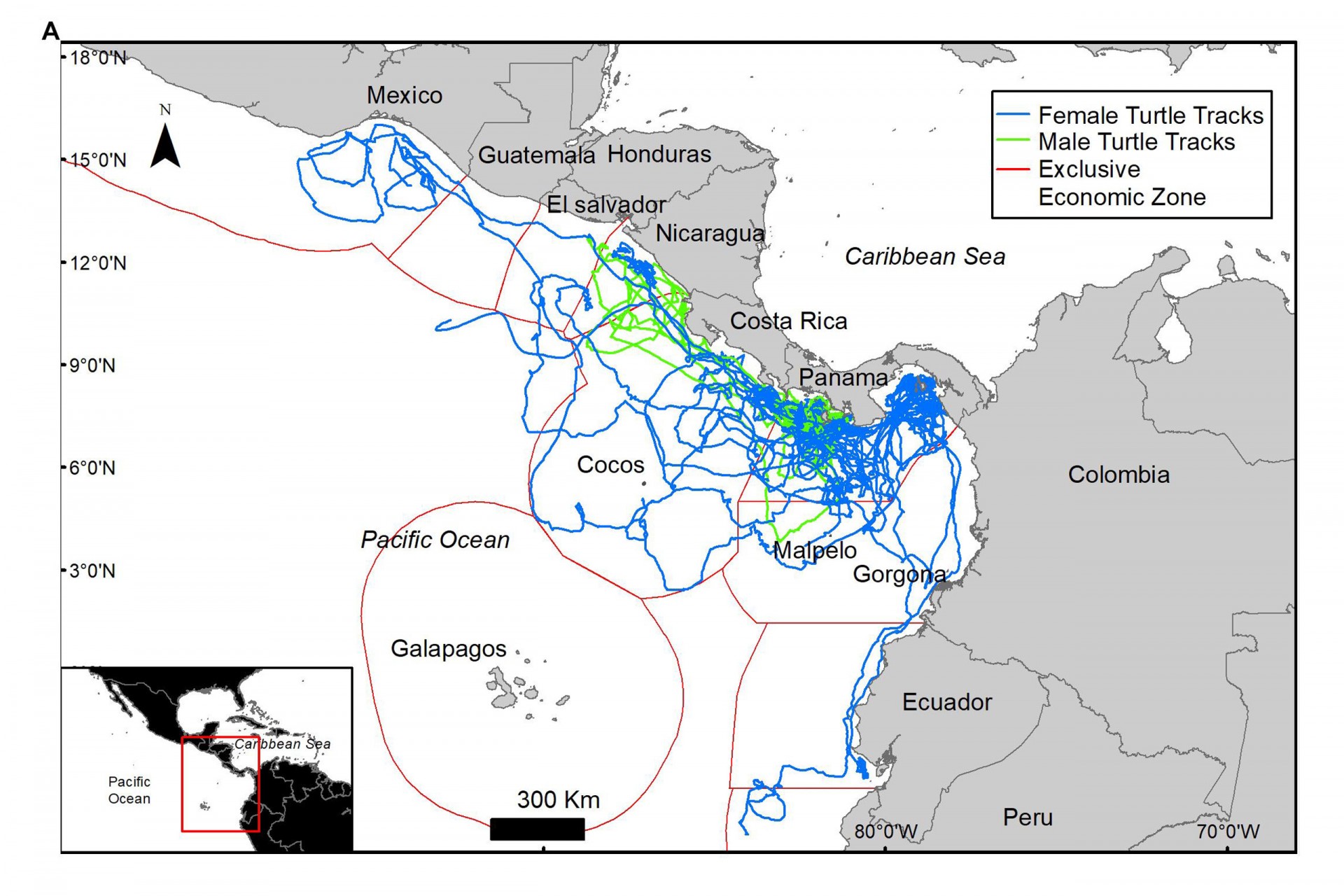

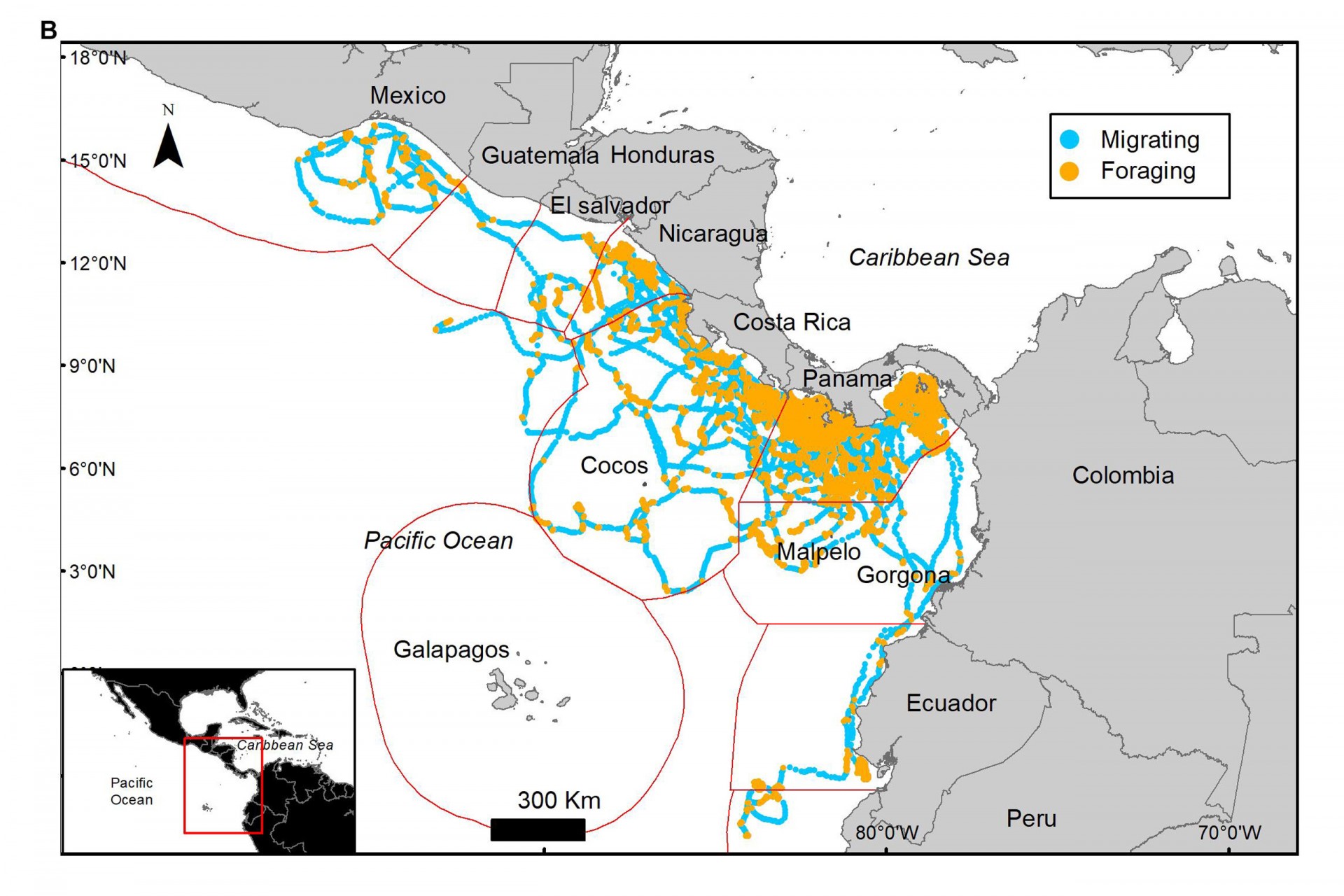

In the case of olive ridley turtles, understanding their migratory patterns is not easy. Their migratory behavior is nomadic: they don’t follow predictable paths like other sea turtle species. This allows them to adapt to dynamic environmental factors, but presents a conservation challenge. If their locations are unpredictable, it is harder to protect them. To figure out their whereabouts, researchers tagged 34 adult olive ridleys in the Gulfs of Panama and Chiriqui with satellite transmitters. The results of tracking their movements are published in Frontiers of Marine Science.

The turtles spent most of their time in areas overlapping with industrial fishing areas, increasing the probability of incidental bycatch; they migrated in multiple directions towards North and South America, driven mainly by local-to-regional environmental conditions, such as ocean currents and food availability; even though individuals did not use the same routes, they often arrived at the same foraging and nesting destinations. The territorial waters of Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Southern Mexico were among their preferred feeding sites.

“This is a transboundary species that climate change may not affect due to the nomadic nature of their movements, and their potential for adapting opportunistically to new feeding areas,” said Hector M. Guzman, STRI marine ecologist and principal author of the study. “Unfortunately, the fishing grounds may change and fishing will continue to impact the species, unless regional policies are endorsed to control the fisheries.”

To reduce the impact of fisheries on turtle mortality, Guzman and colleagues propose the implementation of turtle-safe fishing gear across foraging destinations and education about how to deal with accidentally-caught turtles. Other potential recommendations include increasing the presence of observers on fishing vessels, the establishment of temporary closures in critical areas and protection of nesting habitats.

“Tagged turtles migrated through nine different countries and through international waters,” said Catalina Gomez, co-author and marine biologist at the Centro de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología at the University of Panama. “However, 84 percent of the accidental nettings occurred within the territorial waters of Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia, also the area with the highest overlap with industrial fishing grounds.”

Although olive ridleys in the Eastern Tropical Pacific may appear to be dodging unfavorable environmental conditions, the effect of future climate change on the ocean and on their movements is still hard to predict. As protective legislation is implemented, scientists recommend that turtle movements and behaviors continue to be monitored, to ensure the long-term efficacy of these policies.

Members of the research team are affiliated with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the Centro de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología at the University of Panama. Research was funded by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institution, the International Community Foundation, INGEMAR, S.A., Grupo Eleta, Conservation International, and the Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología de Panamá.

Illustratión by David Serracchiani.