Bright

spot

Plenty of gloom with a dash of hope: Fossils reveal a lone reef in similar state to coral reefs before human impact

Bocas del Toro

Fossil corals show what reefs were like before human impact and reveal a modern “bright spot” reef with apparent long-term resilience to deterioration caused by humans.

Researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) discovered a massive, 7000-year-old fossilized coral reef near the institute’s Bocas del Toro Research Station in Panama. Spanning roughly ~50 hectares, it rewards paleontologists with an unusual glimpse of a “pristine” reef that formed before humans arrived.

“All modern reefs in the Caribbean have been impacted in some way by humans,” said STRI staff scientist Aaron O’Dea. “We wanted to quantify that impact by comparing reefs that formed before and after human settlement.”

Using a large excavator, the team dug 4 meter-deep trenches into the fossil reef and bagged samples of rubble. They dated the reef with high-res radiometric dating. “The fossils are exquisitely preserved,” O’Dea said. “We found branching corals in life position with chemically pristine fossil preservation. Now we are classifying everything from snails and clams to sea urchins, sponge spicules, and shark dermal denticles.”

Archaeological evidence from Bocas del Toro indicates that settlers did not make extensive use of marine resources until around two thousand years ago. So, the fossilized reef predates human impact by a few thousand years. After comparing fossilized corals with corals from nearby reefs, the team was surprised to find a modern reef that closely resembled the pre-settlement reef. They dubbed this a “bright spot,” and asked why this reef is more similar to the prehistoric reef than the others.

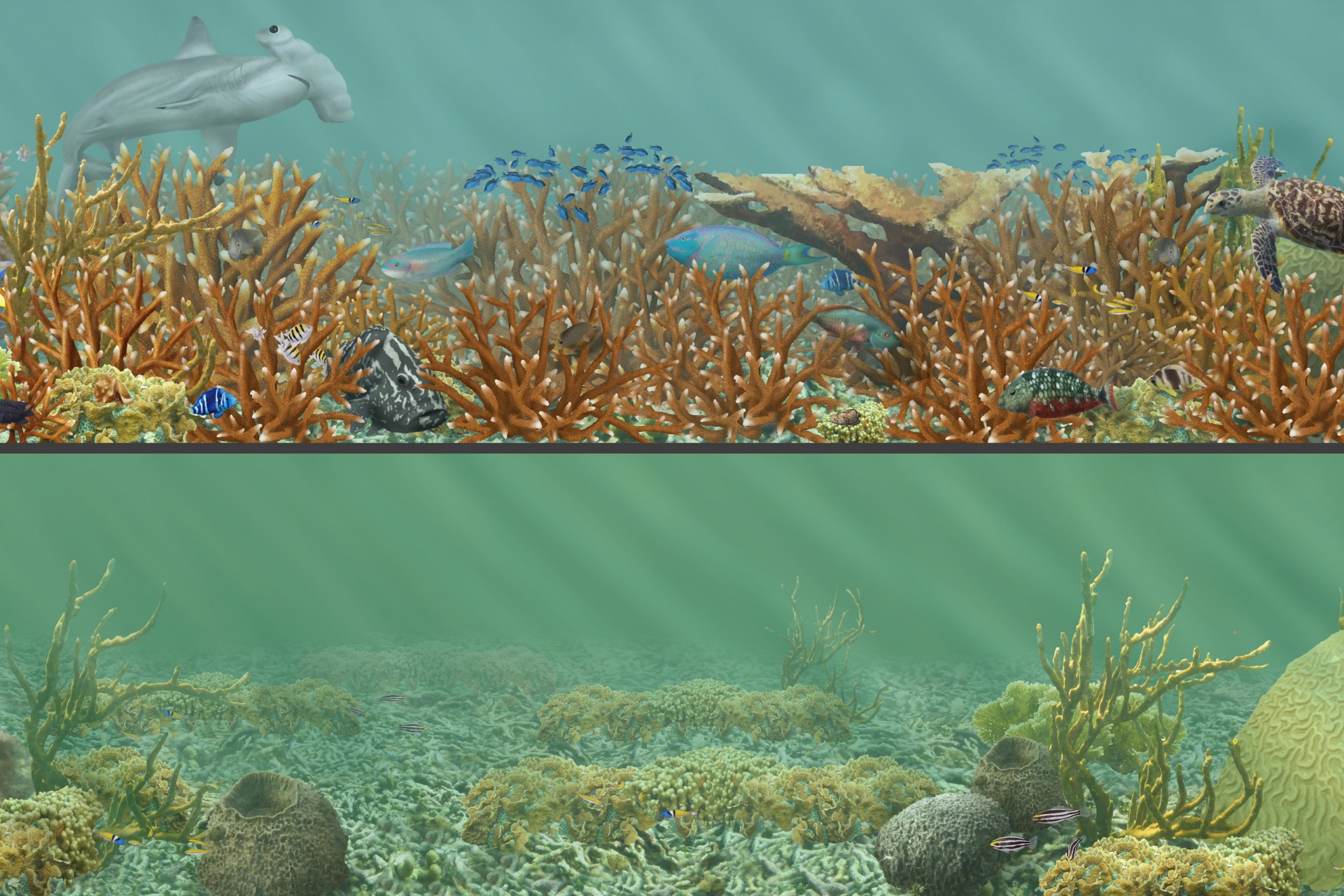

Visualizations of a reef before human impact (above) seven thousand years ago, based on the abundance of fossils. And from a typical degraded reef (below) found today in Almirante Bay in Bocas del Toro, Panama. Illustrations by Kristin Bell, STRI.

Smithsonian staff paleontologist Aaron O’Dea by excavator that revealed fossilized reef. Photo by Felix Rodriguez.

“Most of the reefs in Bocas today look nothing like they did 7000 years ago,” said Andrew Altieri, former STRI scientist now assistant professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. “That confirmed our expectations given what we know about recent deterioration caused by humans. So we were really surprised when we discovered one modern reef indistinguishable in its community composition to the ancient reefs.”

When the team cored this “bright spot” reef, they discovered that it had been in this state for centuries. “This suggests resilience” said Mauro Lepore, former STRI post-doctoral fellow. “And that kind of information can be really powerful for conservation”.

“This finding begs the question of what’s so special about this reef” said O’Dea. The team evaluated current environmental factors such as water quality, hypoxia, temperature, aspect and shape, but none of those explained why this reef is more like the pre-human impact reef. The only clues were that it was the furthest away from human activity and that the staghorn coral, which dominates the reef, had previously been shown to consist of clones resilient to white band disease.

More work is needed to understand why this bright spot persists in the face of human impacts. However, the team propose that these kinds of fossil records can help in conservation by establishing which ecosystems have been irrevocably altered and those which preserve elements of what was natural. Once identified, these “bright spots” could act as a guide to conserve other ecosystems.