Túngara frog tadpoles that grew up in the city developed faster but ended up being smaller.

Hamlet

Evolution

A comparison of colorful hamlets

from the Caribbean challenges ideas

about how species arise

By: Beth King

Scientists have been thinking about how new species evolve since Darwin wrote On The Origin of Species in 1859. The results presented here call into question some of the most common explanations of how species originate.

Toddlers can name a few animals. Older kids group animals into categories (birds, fish). And teenagers can sketch a rough tree of life. But when 16 grown-up biologists—five of them affiliated with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute—try to explain why colorful reef fishes called hamlets are different species, it gets complicated. Their results in the journal Science Advances challenge common explanations about using genetic differences to tell species apart.

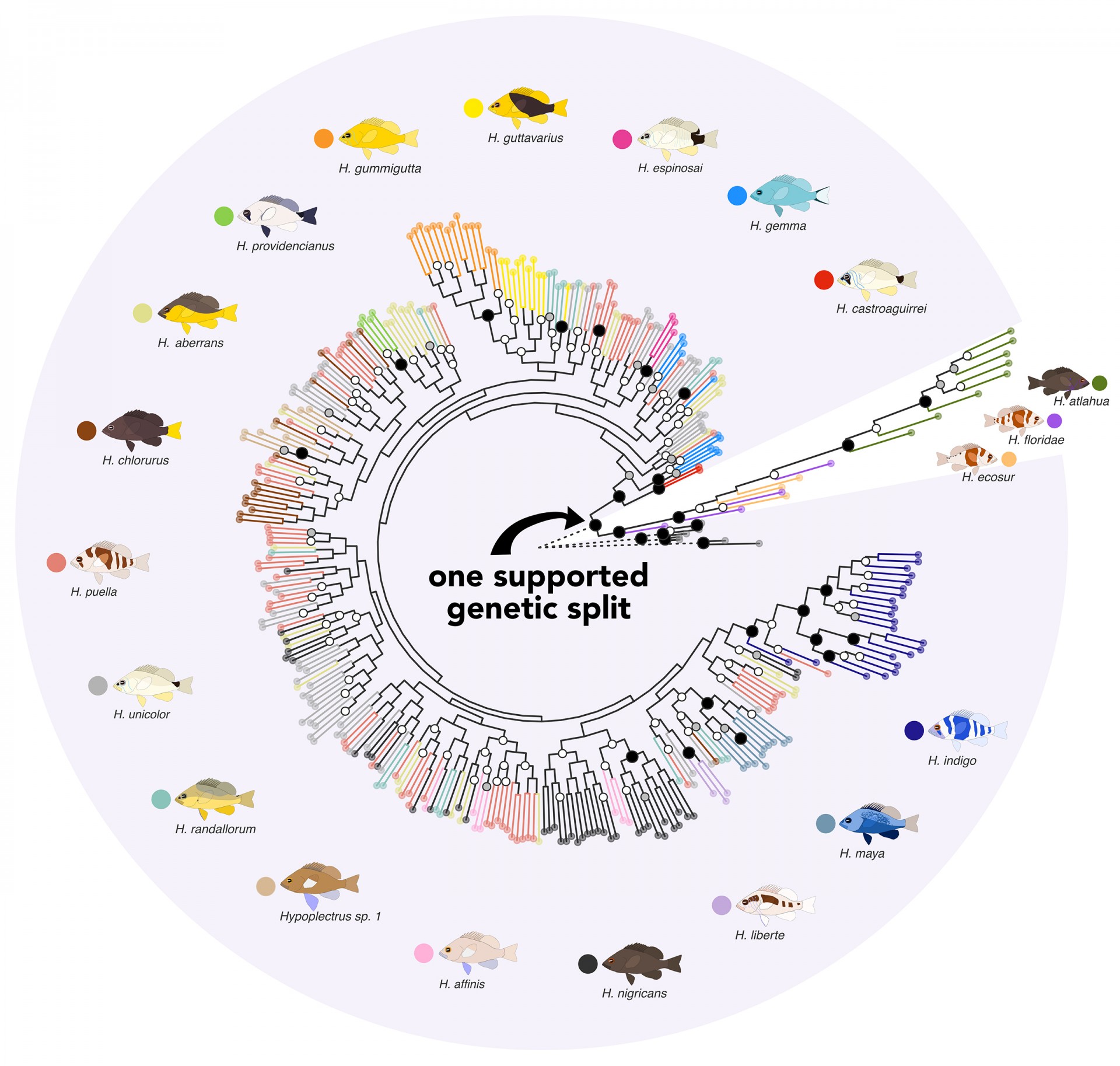

“Most studies explaining how the different species in a group evolve begin by showing a family tree based on the genetic differences between the species,” said Oscar Puebla, senior author, STRI Research Associate, and professor at the Leibnitz Center for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT) in Germany. “But in this case, there is just one genetic split among all 19 species of hamlets.”

Phylogeny and nucleotide diversity of the hamlet radiation.

Credit: Authors, Science Advances article

Species form when animals adapt to new conditions. Animals that can’t adapt die out and the ones that can adapt reproduce, becoming so genetically different that they can no longer interbreed with other animals in the original group. Maybe the animals were isolated in space, like on the opposite sides of a mountain range; or their paths never crossed because they were active at different times of day…but overall, no matter the cause, they became genetically different. In the early stages of species differentiation, animals may still interbreed and only differ at genes that are directly relevant to adaptation—the genic view of speciation. In principle, these genes should allow researchers to reconstruct a family tree.

“To our surprise, when we looked at the genetic data, we realized that no single gene allows us to reconstruct a family tree for the group,” said Martin Helmkampf, senior researcher at ZMT. “And we are sure of this because we screened the entire genomes of 335 fishes. This challenges how people think about what species are and how they arise.”

Co-authors Floriane Coulmance, the first winner of the D. Ross Robertson Postdoctoral Fellowship for Field Studies on Neotropical Reef Fishes, now at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, and Melanie Heckwolf, former post-doctoral fellow at STRI, developed an innovative underwater camera with a color chart, making it possible to describe the colors of living fish pixel by pixel and to compare colors even when the fish were photographed under very different light conditions. Read about that here in our web story, “Living Color.”

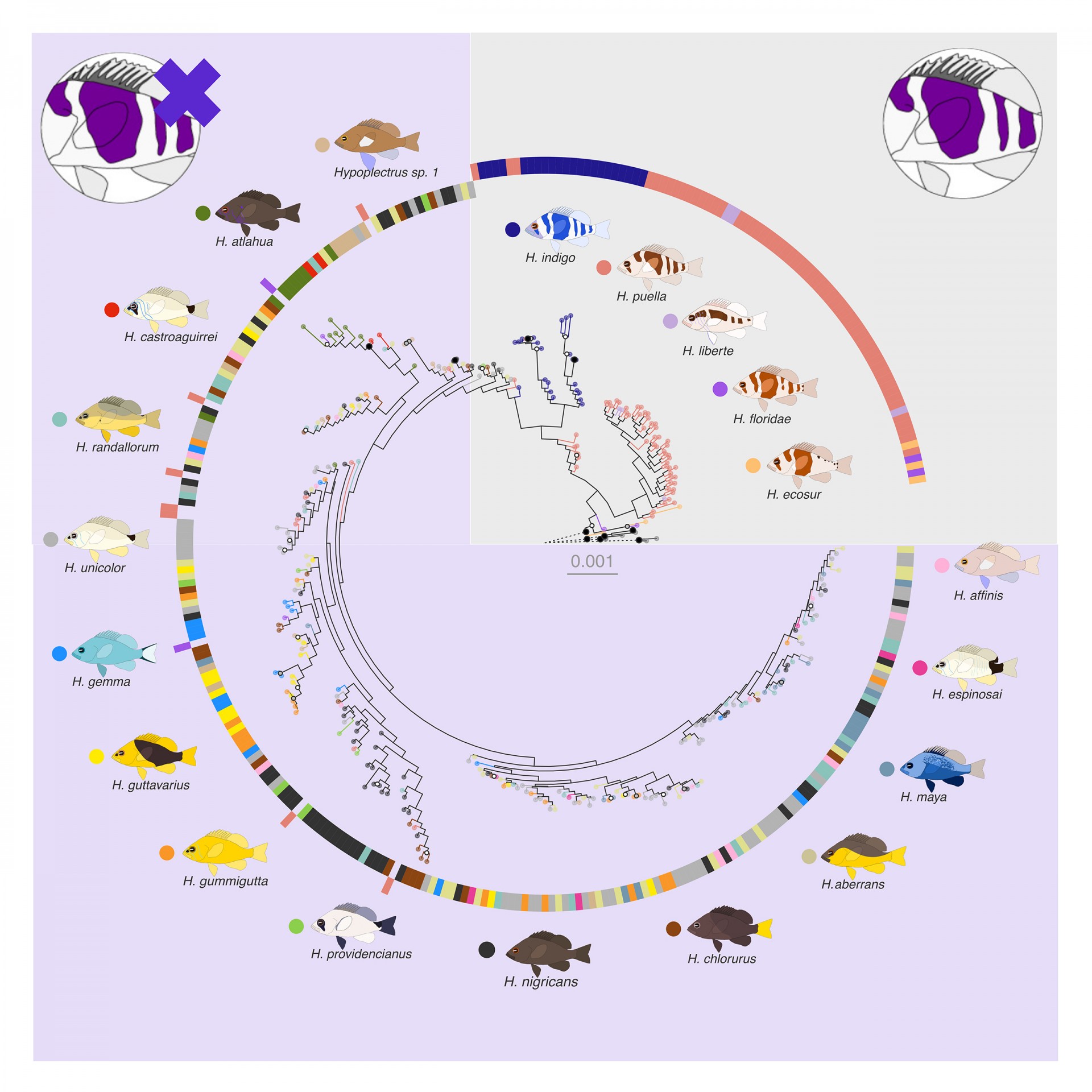

Genome-wide association study for species identity and casz1 gene tree.

Credit: Authors, Science Advances article

Later, researchers in the group sequenced the entire genomes of 335 fish. Based on the color data and the genetic data, they identified just one gene that seems to be involved in species differences. This gene, called casz1 is expressed in the skin, eyes and brain of hamlets and it is probably responsible for determining color patterns and mate choice. However, even this gene does not allow researchers to reconstruct a family tree for the group. This is probably because species differences are encoded by many genes that act in concert.

“So, in the end, we have to live with the fact that in some cases it is impossible to reconstruct a family tree that differentiates the species,” said Helmkampf.

There is a very similar explanation for speciation in the Heliconius butterflies, studied at the Smithsonian’s laboratories in Gamboa, Panama. As Owen McMillan, STRI staff scientist and coauthor of the study says: “If there is one thing that we’ve learned from our ability to sequence the genomes of many individuals, it’s just how fluid the boundaries are between what we call species. Hybridization among species occurs a lot and it is turning out to be an important way to rapidly evolve new traits and/or exploit new environments in everything from humans to butterflies, birds, and coral reef fishes. It is also a way to rapidly evolve new species, something we see in butterflies, and is probably occurring in hamlets. Of course this makes sorting things into defined groups challenging, but it is a remarkable testament to how evolution works to create Earth’s biodiversity.”

“Two yellowbelly hamlets (Hypoplectrus aberrans) spawning in Dominica. The hamlets are simultaneous hermaphrodites. The individual on top, adopting a bowed “U” shape, spawns in the male role while the individual below spawns in the female role.

Credit ©Carlos & Allison Estapé, carlosestape.photoshelter.com”.

Affiliations of the 16 authors include: The Leibnitz Center for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT); the Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment (ICBM); the Carlo von Ossietsky Universität Oldenburg; the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI); the Instituto para el Estudio de las Ciencias del Mar (CECIMAR); the Universidad Nacional de Colombia sede Caribe; the Corporation Center of Excellence in Marine Science (CEMarin); the Division of Biosciences, Faculty of Life Science, University College London (UCL); the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum, Frankfurt am Main; the LOEWE Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; the Wellcome Sanger Institute, Tree of Life, Wellcome Genome Campus, Cambridge; the Laboratorio de Biología Acuática, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás Hidalgo; el Laboratorio Nacional de Análisis y Síntesis Ecológica para la Conservación de Recursos Genéticos de México, Escuela Nacional de Estudios Superiores, Unidad Morelia, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Morélia; the Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences, Brigham Young University; the Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology (IKMB), Kiel University; School of Biological Sciences, The University of Oklahoma, Norman; el Departamento de Biología, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia; the Ocean Science Foundation, Irvine; the Guy Harvey Research Institute; the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California.

About the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute

Headquartered in Panama City, Panama, STRI is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, USA. Our mission is to understand tropical biodiversity and its importance to human welfare, to train students to conduct research in the tropics and to promote conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems. Watch our video, and visit our website, Facebook, X and Instagram for updates.

Reference: Helmkampf M, Coulmance F, Heckwolf MJ, Acero A, Balard A, Bista I, Dominguez O, Frandsen PB, Torres-Oliva M, Santaquieteria A, Tavera J, Victor BC, Robertson DR, Betancur-R R, McMillan WO, Puebla O. 2025. Radiation with reproductive isolation in the near absence of phylogenetic signal. Science Advances.