Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Yellow

submarine

An expedition to

the depths of the ocean

Text by Leila Nilipour

Two weeks exploring the Cordillera de Coiba revealed clues about this unknown region.

After almost 30 hours of sailing from Panama City, the M/V Argo, with six researchers and two science communicators on board, stopped near the fifth parallel: a few meters from the line that divides Panamanian and Colombian waters. A long underwater mountain range shared by both countries rose from the sea floor, one of its peaks directly below the ship, at a depth of about 130 meters. The Colombian side of the seamount had been explored before, but the Panamanian side had not. The scientific expedition led by marine ecologist Héctor Guzmán from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and MigraMar, and with researchers from Costa Rica, Ecuador, Colombia and Panama, would be the first to do so.

The scientists on board represented four countries with highly connected marine protected areas: Panama, Costa Rica, Colombia and Ecuador. Understanding the biodiversity in the Cordillera de Coiba will benefit conservation efforts as a whole. Credit: Ana Endara, STRI.

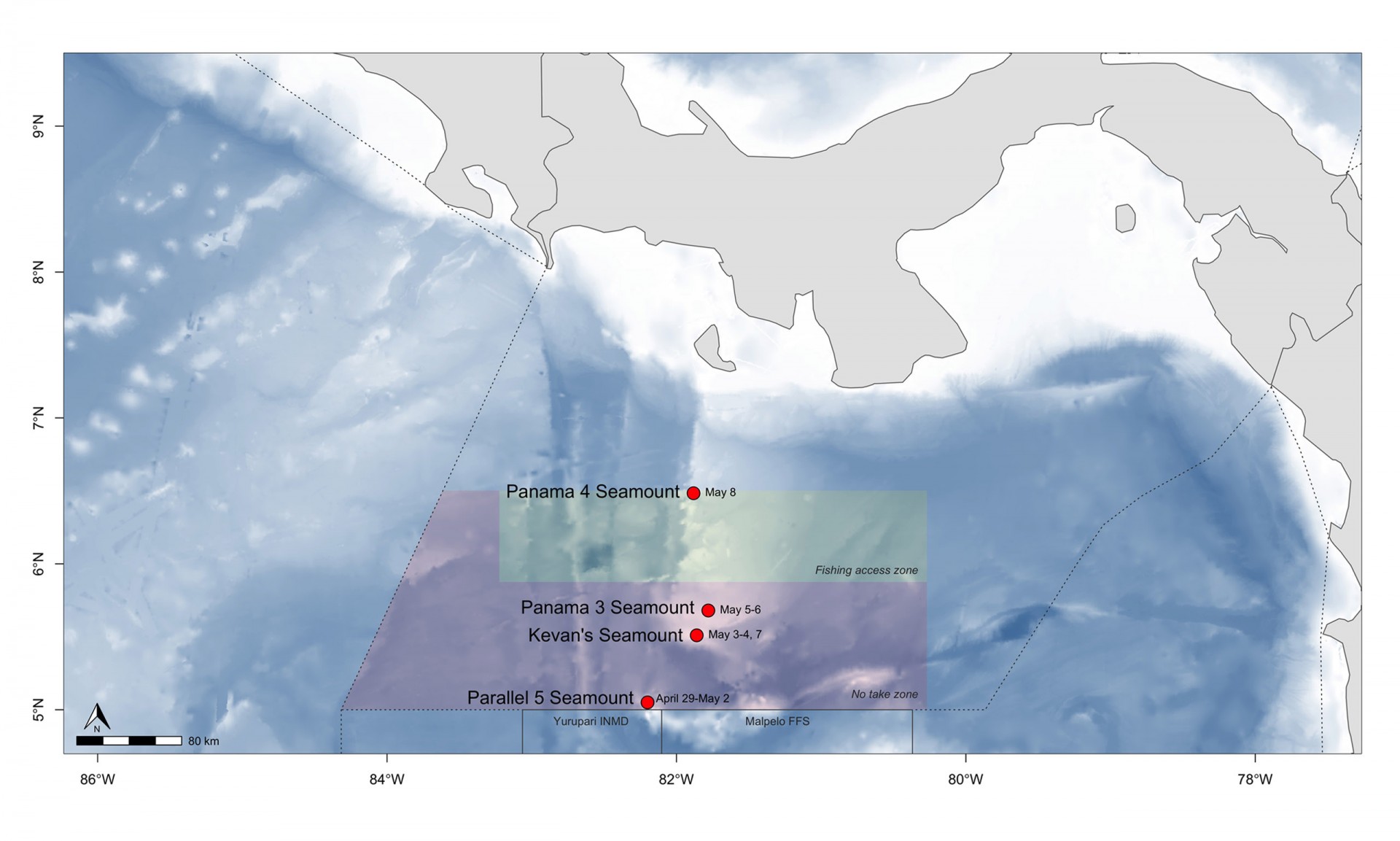

The map produced at the end of the expedition shows the different points of the Cordillera de Coiba that were explored over two weeks. Credit: César Peñaherrera, Migramar.

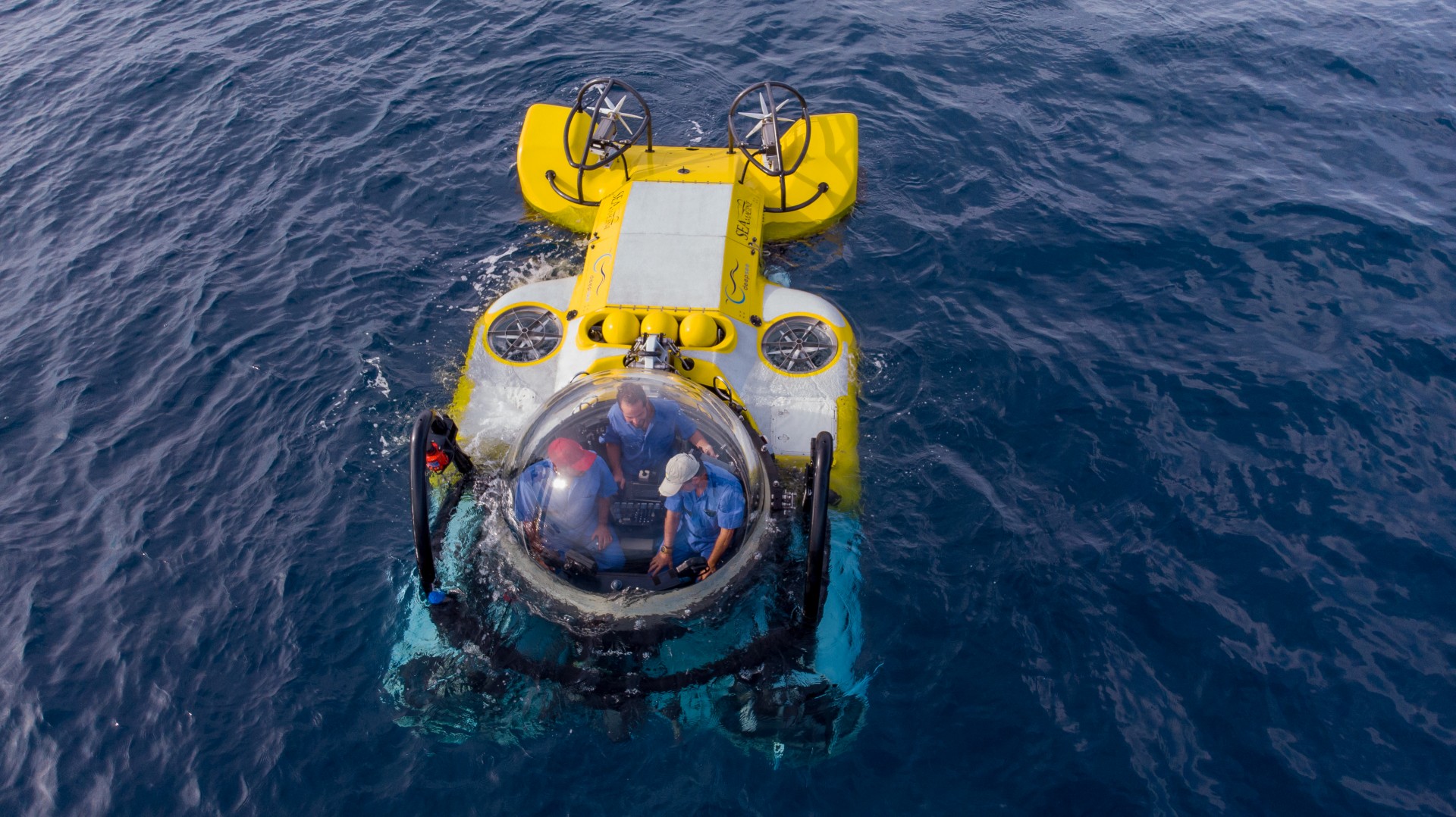

In the style of French explorer Jacques Cousteau, Guzman would descend twice a day in the DeepSee, a three-seater yellow submarine piloted by the crew of the Argo, reaching up to 350 meters deep—about ten times deeper than a technical dive. He would explore not only the seamount located on the fifth parallel, but also three other mounts linked by the same underwater mountain range that connects Panama with Costa Rica, Ecuador and Colombia. Known as the Cordillera de Coiba, this range is also the centerpiece of a marine protected area that the Government of Panama recently expanded to 68,000 km2, making it possible for the country to achieve the United Nations 2030 goal of protecting 30% of its oceans nine years ahead of the target date.

"Panama has taken a giant step forward and is leading the region in conservation issues," said César Peñaherrera, PhD in quantitative marine sciences at Migramar and one of the scientists on the expedition. "In less than seven years it has managed not only to create new marine protected areas, but to meet many of the goals of the global 30x30 initiative."

The data collected during the ten days at sea would help to better understand and protect the marine reserve designated by Mission Blue as a Hope Spot: a unique place that has been identified as critical to the health of the oceans.

The DeepSee submarine allowed the exploration of some of the shallowest seamounts in the Cordillera de Coiba, between 130 and 350 meters deep. Credit: Ana Endara, STRI.

Deep in the water, where the sun's glare no longer reaches and the blue sea turns black, the DeepSee turned on its headlights and began to explore the seamounts. Eleven dives on the two shallowest mounts detected during the expedition revealed an abundance of a yellow soft coral, which was collected and will be analyzed to determine if it is a new species. A diversity of fish, eels, sponges, sea cucumbers, crustaceans and starfish, among others, were also found. Several kilos of rock were collected to better understand their geological origin and to be able to compare the mount with Hannibal Bank, 200 miles north.

Eleven submarine dives revealed the abundance of a yellow soft coral in the two seamounts explored during the expedition. Samples were collected to determine if it is a new species. Credit: Ana Endara, STRI.

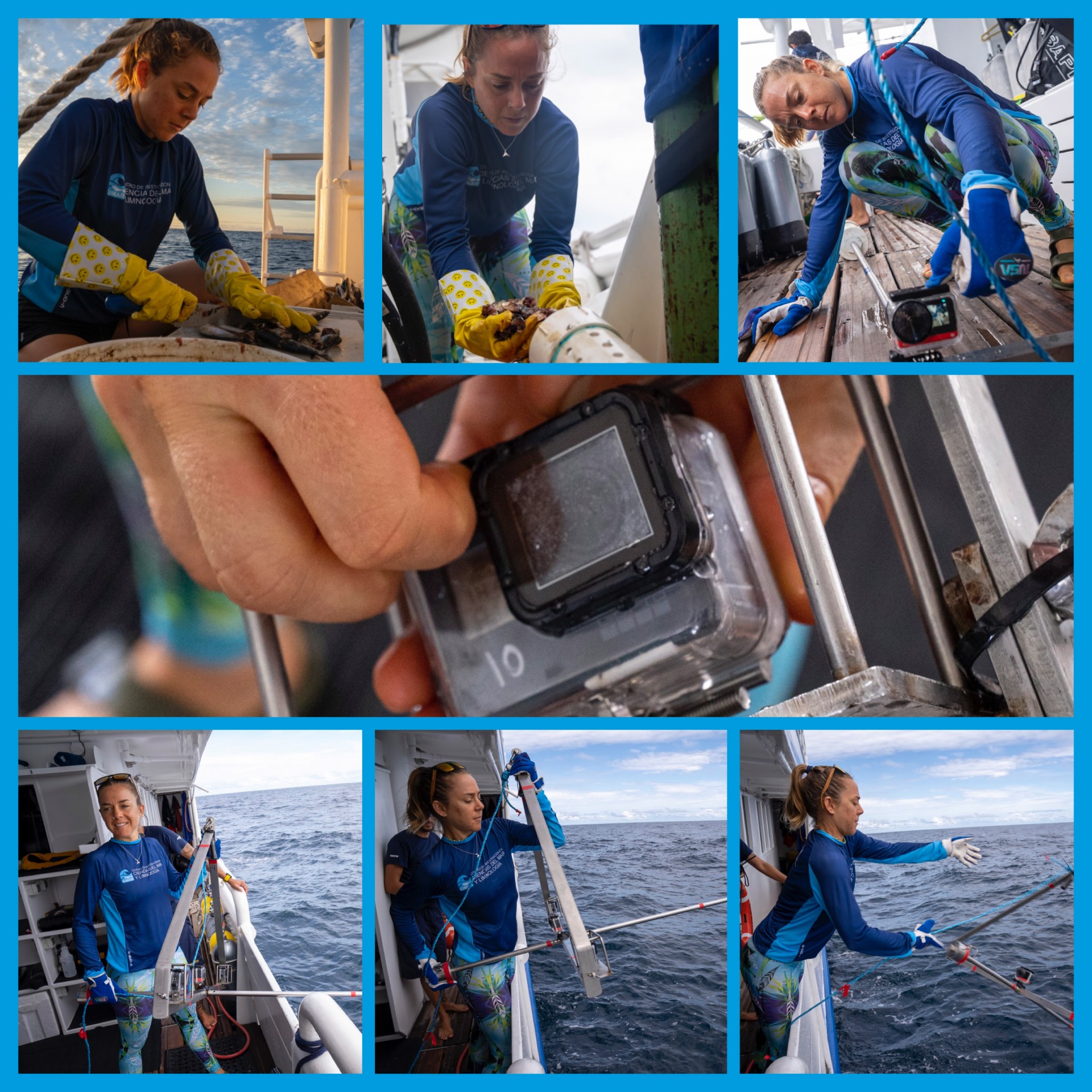

Pelagic species—such as sharks, sailfish, rays and turtles—were monitored at a depth of 10 meters by baited remote underwater video systems (BRUVS), stainless steel structures with three video cameras and a container of chopped fish designed to attract them with their scent. Since seamounts are aggregation areas for migratory marine species, expectations were high to discover which animals were circulating around the Cordillera de Coiba.

The first sightings with the BRUVs did not take long. From the beginning, sharks were observed, including the rare thresher shark (Alopias pelagicus) and a school of approximately 60 hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini), a critically endangered species. Another big surprise was the appearance of a Masturus lanceolatus, or sharptail mola, towards the end of the expedition, as it is a fish that lives in oceans around the world, but is rarely detected. In total, some 900 hours of video were collected, including 360-degree videos, which will be analyzed in more detail later. Preliminarily, however, the findings suggest that this may be an important area for migratory marine species.

Pelagic species—such as sharks, sailfish, rays, or turtles—were monitored using baited remote underwater video systems, or BRUVS, which were placed 10 meters deep several times a day. Credit: Ana Endara, STRI.

The submarine dives also surprised researchers on the last day of exploration: a site was detected with an abundance of prickly sharks (Echinorhinus cookei), a deep-sea species of which very little is known, as it is not easy to observe. The find was made on a seamount named by Guzman in honor of the recently deceased marine explorer and Coiba National Park diver, Kevan Mantell.

“Our expedition was complex, its success depended on the extraordinary effort and teamwork of the scientific staff alongside the crew from the ship and submarine,” said Guzmán. “We achieved our initial goals, assessing migratory species and exploring never-before-seen seamounts that stand out in this great country yearning for science and discovery.”

“Three cheers to Hope Spot Champion Héctor Guzmán and our partners from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and MigraMar for taking action to explore and document this special blue pocket on Earth," said Mission Blue founder Sylvia Earle. "We know more today than ever before what’s at stake for the ocean –and for us– and I applaud their work on this important expedition. I am greatly looking forward to the country of Panama stepping up to further protect the marine life within its waters.”

The data collection during two weeks on the high seas was accomplished thanks to the efforts of scientists representing STRI, MigraMar, the International Maritime University of Panama (UMIP), the University of Costa Rica and the Center for Research in Marine Sciences and Limnology (CIMAR), Malpelo Foundation, as well as the unconditional support of the crew of the M/V Argo of Undersea Hunter Group. Credit: Ana Endara, Héctor Guzmán, STRI.

Despite the exciting and eye-opening discoveries of this first scientific expedition to the Cordillera de Coiba, some moments were less hopeful. Throughout the trip it was common to observe trash floating on the high seas, especially plastic bottles. Several fishing lines were observed, stuck in the seamounts.

And finally, a small vessel was identified sailing close to the Argo during the midpoint of the expedition, which was shark finning in the marine protected area, a cruel and illegal practice prohibited in Panama and which threatens shark populations and the general health of the oceans. Coincidentally, on the days that vessel was close to the scientific expedition, the amount of marine fauna recorded on the BRUVS was drastically reduced. The implementation of the recently approved management plan for the Cordillera, which includes a satellite monitoring system, will be critical for ensuring this is a genuinely protected area.

There were also less hopeful moments along the journey, such as the frequency with which plastic garbage was seen floating nearby or the various fishing lines stuck in the seamounts of the marine protected area. Credit: Ana Endara, STRI.

This first scientific exploratory mission was made possible thanks to funding from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the STRI Advisory Board, the Collatos Family Foundation, the Hothem family, Re:wild, the Wyss Foundation and Mission Blue, as well as the efforts of scientists representing STRI, MigraMar, the International Maritime University of Panama (UMIP), the University of Costa Rica and the Center for Research in Marine Sciences and Limnology (CIMAR), Malpelo Foundation and the unconditional support of the crew of the M/V Argo of Undersea Hunter Group.