Smithsonian science helps understand blue whale migratory and foraging patterns to inform conservation strategies

Super

corals?

Yacht Acadia Expedition: are eastern pacific corals climate change survivors?

An entrepreneur who dreamed of becoming an oceanographer teams up with STRI researchers and young Latin American biologists to find out if some coral reefs are more resilient than others. His yacht will be the center of operations as they deploy high tech sensor arrays at sites around the tropical eastern Pacific.

Coral reefs cover 1% of the Earth’s surface – but are home to 25% of the world’s marine species. Reefs are under threat from climate change, but a team of researchers from STRI has embarked on a four-year quest to solve a tantalizing mystery: why do some corals in the Tropical Eastern Pacific seem to be more resistant to the damaging effects of climate change than corals elsewhere? By unlocking the secrets of these “super-corals,” they hope to help rescue and restore coral reefs worldwide.

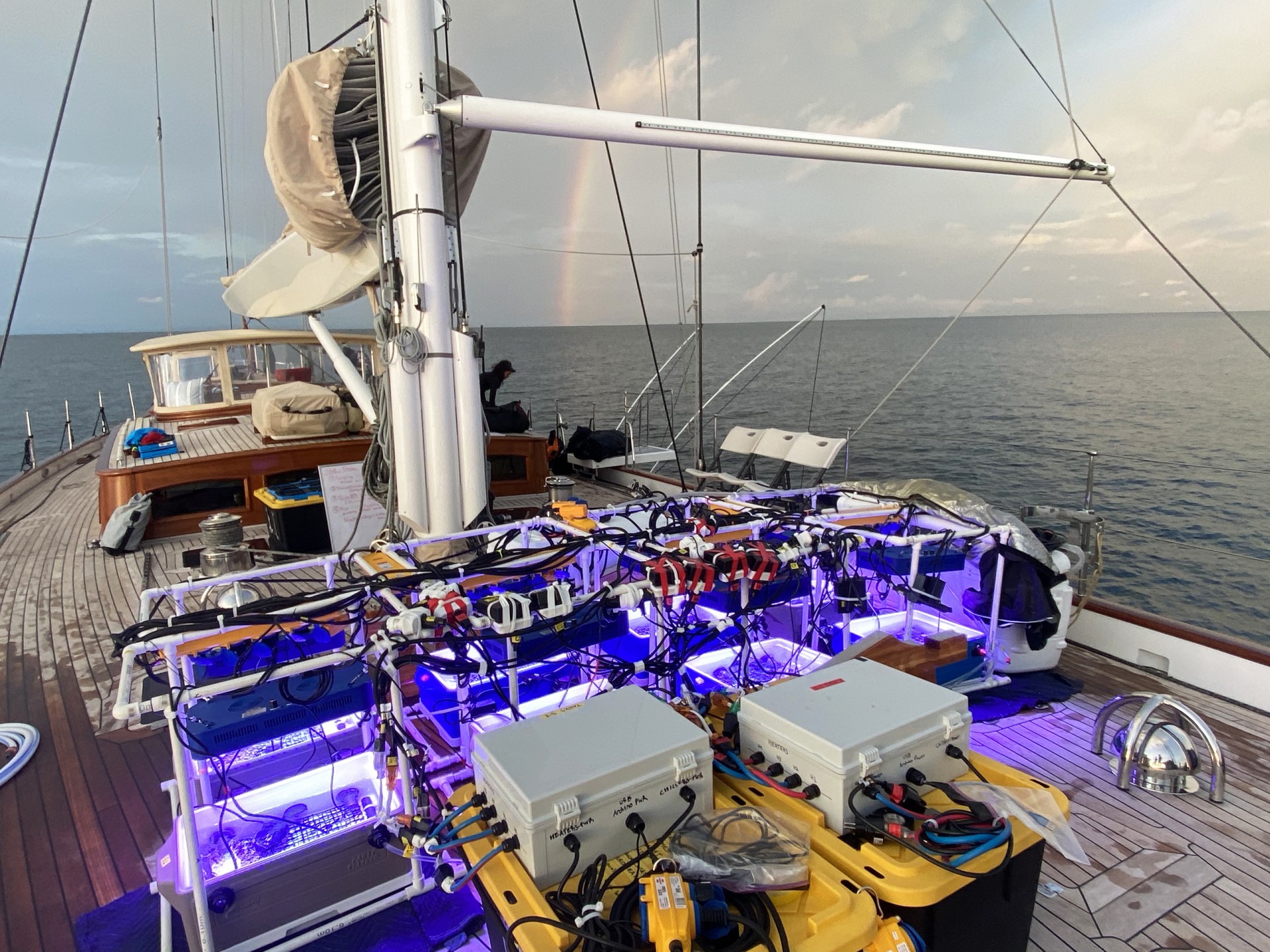

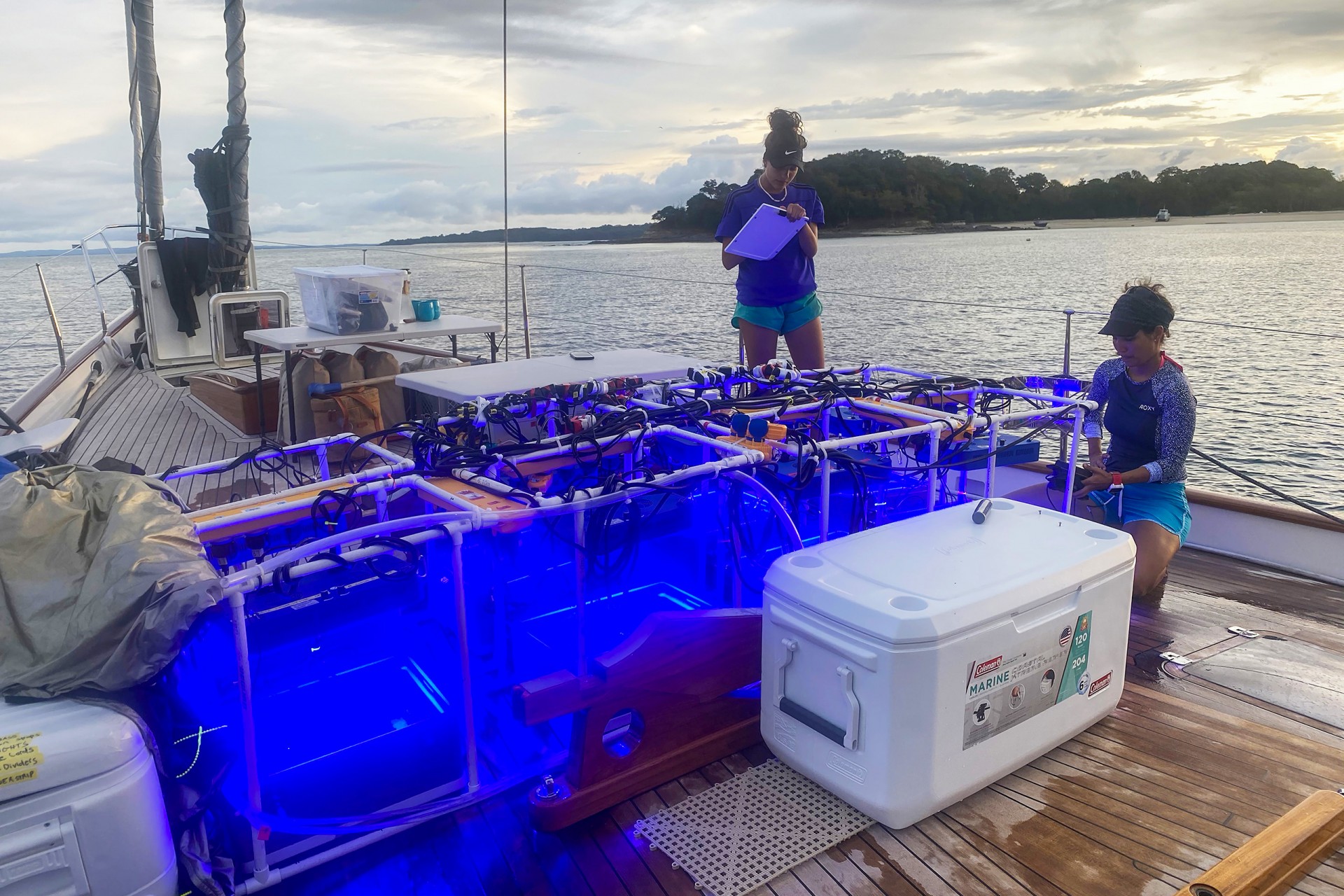

Custom coral bleaching resilience testing system on the deck of the yacht, Acadia: rainbow in the background. This experimental bleaching system exposes 11 genotypes of corals to eight different water temperatures to determine which coral genotypes are the most resilient and susceptible to bleaching. We performed bleaching resilience experiments at three reef sites in Panama’s Las Perlas Archipelago and three reef sites in Coiba National Park. Credit: David Kline.

During the next four years, STRI’s David Kline, Matthieu Leray, Sean Connolly and Mark Torchin, aided by a new generation of student scientists from Brazil, Panama, Honduras, the U.S. and elsewhere, will convert entrepreneur Mark Rohr’s super-yacht, the Acadia, into their flagship.

Each year the team plans to sample reefs from Panama’s largely unexplored Coiba National Park (Dec. 2020), site of STRI’s newest research station and the Galapagos (June 2021). Later, they will sail to the Revillagigedo Islands, off of the Mexican coast, and hopefully to the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia and the Phoenix Islands in the Republic of Kiribati. Rohr, who dreamed of becoming an oceanographer before becoming the owner of a Fortune 500 company, recently funded the four-year project. Part of this funding will support students and post-docs, with the goal training local experts who can follow up on project goals in the future.

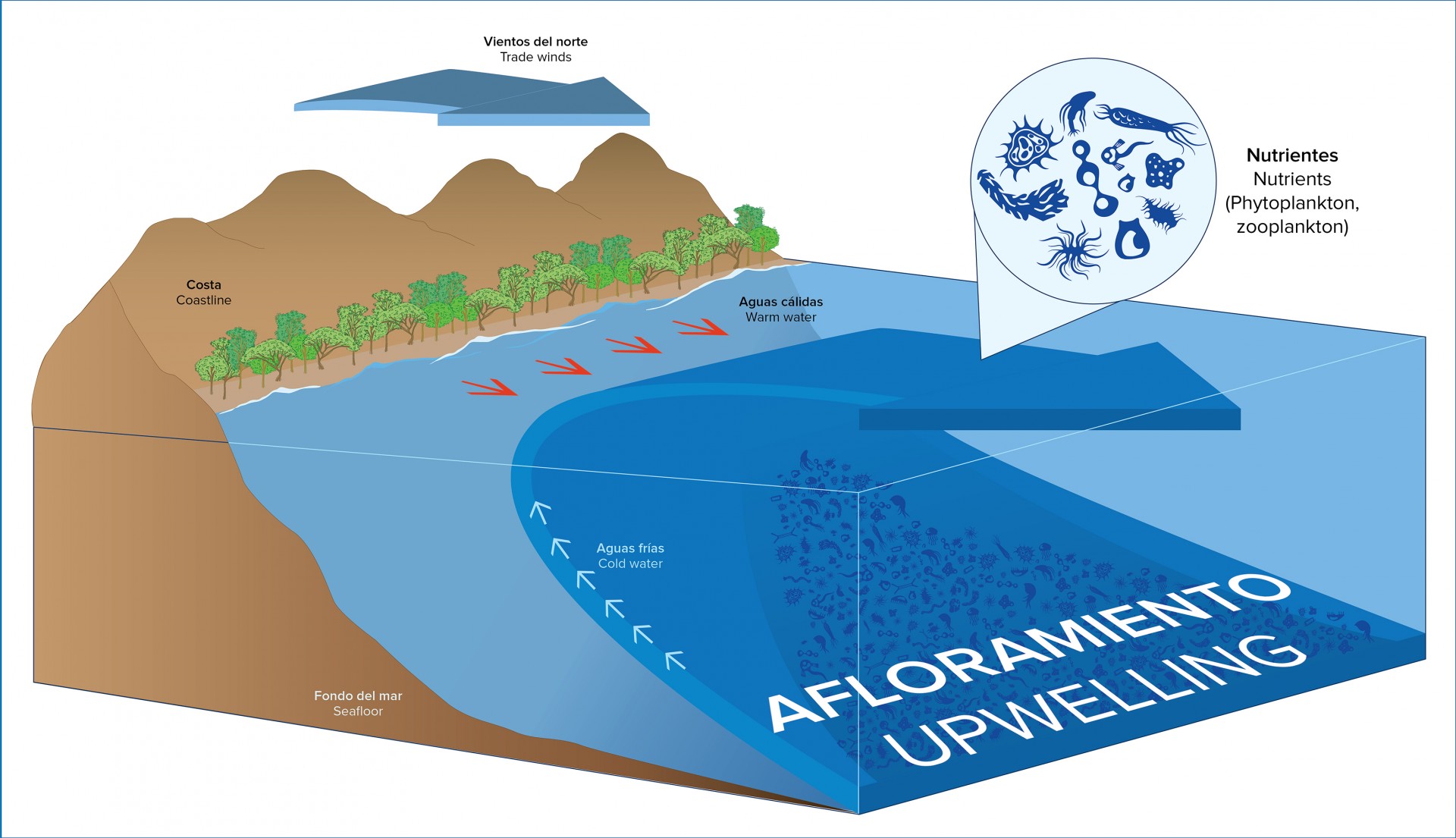

The sites are special because they experience substantial variations in climate conditions (including temperature, pH and nutrients) every year. They represent different levels of “upwelling,” a phenomenon that happens when strong winds push warm surface water away and cold water from the ocean bottom comes surging up. In places like the Gulf of Panama, this happens each year when the trade winds blow south during the winter. Other sites such as Coiba are protected from upwelling by tall mountain ranges that block the wind. What’s more, these reefs are also subjected to extremely high temperatures during El Niño years.

The team hopes to understand how Pacific coral reefs have weathered not only the passage of time, but abrupt shifts in temperature, ocean acidity and nutrient levels in upwelling zones, and to apply what they find out to saving one of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems.

Strong trade winds blowing from the east to west (from the Caribbean toward the Pacific) are mostly blocked by the mountains of Central America. But where they cross low areas in the mountain chain, they blow the warm surface waters of the Pacific towards the west. This acts as a pump: deeper, cold water carrying nutrients rises to the surface, providing food for fish. Upwelling during Panama’s dry season makes the Bay of Panama a rich fishery. Illustration: Paulette Guardia.

The scientists will put new tools to work as they revolutionize ocean science research. David Kline has developed a collaboration with Conservify, a non-profit with funding from Google and others to develop low-cost sensor arrays called FieldKits that have been deployed in rainforests across the Amazon, and will be modified for marine applications for this project. For this project, they will develop custom marine sensor arrays to measure pH, temperature and light next to the corals throughout the 4-year program. The project will also use advances from Silicon Valley including Structure from Motion and Machine Learning to create high resolution 3D photographic reef models. “Conservation tech is really changing the way we study reefs,” says Kline. “We can use 3D scanners developed for autonomous cars, and machine learning to identify the organisms in millions of photos.”

And although the team will have amazing visuals, they won’t have to see all of the organisms present to identify them. Matthieu Leray plans to use genetic techniques to do what forensic experts have been doing at crime scenes. Based on DNA collected from water samples, he will be able to tell if a whale, a barracuda or a shrimp has been in the area. In a recent study of this eDNA (environmental DNA) in the Caribbean, Leray and his team identified DNA from 9000 different organisms near STRI’s Bocas del Toro field station, many more than they could identify via visual surveys of the same area.

Animals, plants and microbes associated with corals may be protecting reefs by producing chemicals that keep predators away or slimy coatings or by eating the predators before they can eat the reef. “The corals may be 500 years old, and may evolve fairly slowly, but the bacteria on a reef may be evolving much more quickly—and may protect the reef from changing conditions,” Leray said.

Coral reef where Pocillopora coral dominates, here with a cloud of plankton-eating fish in Panama’s Coiba National Park. Credit: Natasha Hinojosa.

Sean Connolly will create sophisticated mathematical models that help to understand how the reef is changing at different sites, and Mark Torchin will apply his expertise of invasive marine organisms.

Communicating to a broader audience about the discovery of these super-corals and conservation will include the team’s underwater photography, watercolor and graphic art from one of the fellows, and film clips. All of the team are expert divers and several are underwater photographers. One student is a graphic artist.

King angelfish hiding amongst Pocillopora damicornis corals in Panama’s Coiba National Park This is our target coral species and the dominant coral in the Tropical Eastern Pacific. Credit: Natasha Hinojosa.

Answers to some of the team’s research questions will probably start coming in two years. If they can unlock the secrets of the super corals – the ways in which they’re successfully resisting the effects of climate change – they may be able to develop ways of protecting other corals and coral reefs globally.