For the first time since records began,

the cold, nutrient-rich waters of the

Gulf of Panama failed to emerge

Migration

Decoded

Smithsonian science helps understand blue whale migratory and foraging patterns to inform conservation strategies

By: Sonia Tejada – Translation: Sonia Tejada

A new study led by researchers from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) is the first to satellite-tag blue whales in the Galapagos, exploring their behavior in relation to environmental variables

The Galapagos Islands are renowned for their marine mammal diversity, particularly cetaceans, with 23 species documented, including both residents and migratory species. The Galapagos Marine Reserve provides an essential habitat for foraging, resting, and potentially breeding for the largest of all species, the blue whale.

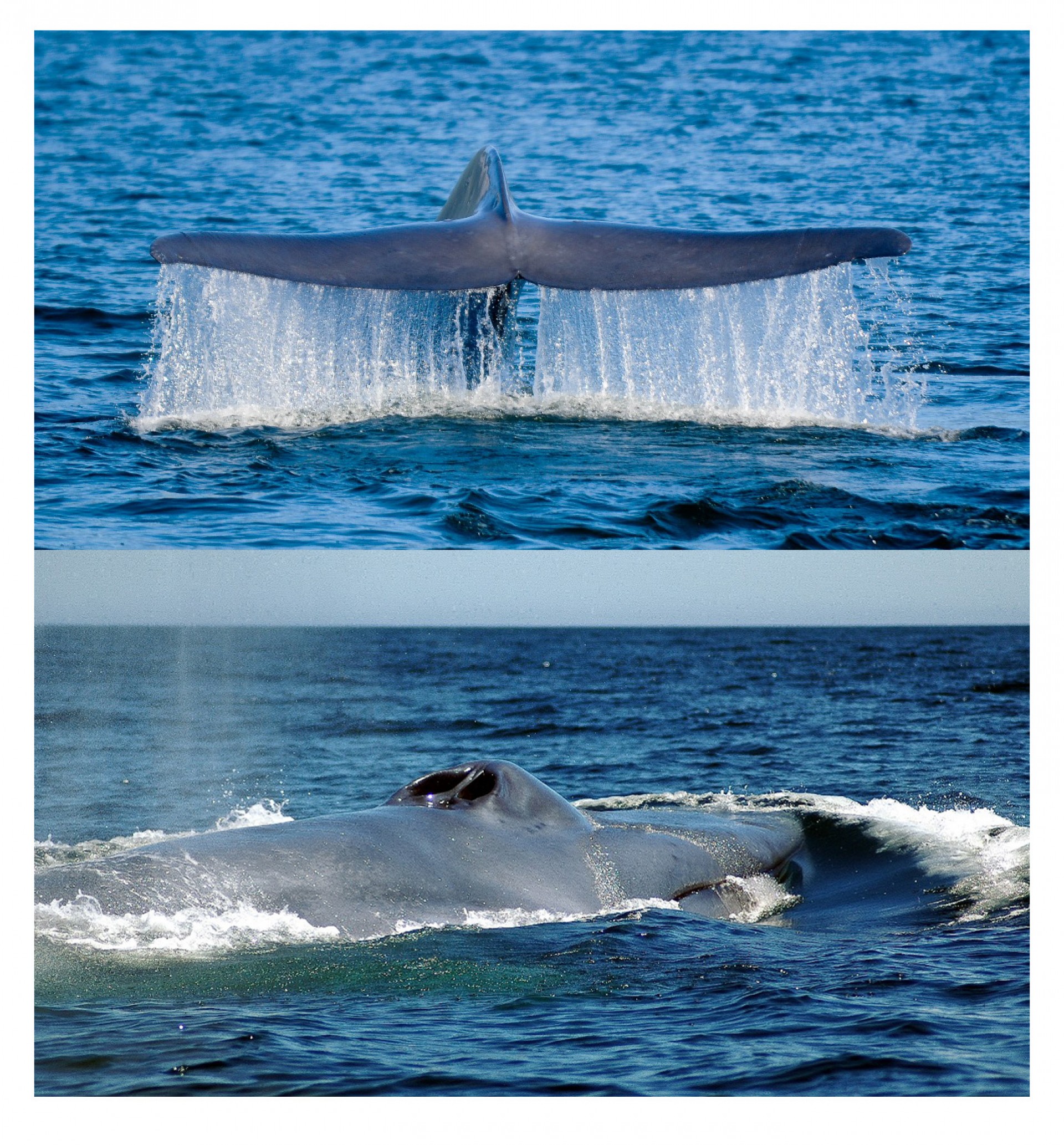

Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) are krill-feeding mammals (Krill are tiny, shrimp-like crustaceans found in the ocean) that can reach almost 30 meters (100 feet long) and live for 80 to 90 years. They are currently classified as Endangered according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species; decades of intensive commercial whaling decimated their populations, especially in the Southern Ocean, pushing them to the brink of extinction. Although some regions show signs of recovery, populations remain well below pre-whaling levels.

Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) are krill-feeding mammals that can reach almost 30 meters (100 feet long) and live for 80 to 90 years.

Credit: Image courtesy of Rodrigo Hucke-Gaete

Scientists want to understand more about their migratory behavior within the Galapagos and the broader Eastern Tropical Pacific.

The study, done between 2021 and 2023, used satellite telemetry, a system for collecting and transmitting data on blue whales to monitor their movements and gain insights into their interactions with the marine environment. Sixteen blue whales were tagged with transmitters in the Galapagos Archipelago, all during the Austral winter season (May-October), specifically during the period with the highest number of sightings.

From where they were tagged, the whales journeyed in various directions, covering a maximum distance of approximately 2,400 kilometers over 98 days. This translates to an average speed of 25 kilometers per day or 1 kilometer per hour.

Blues whales are still endangered. They migrate between feeding grounds near the poles and tropic breeding grounds.

Credit: Image courtesy of Rodrigo Hucke-Gaete

Scientists hoped to identify their feeding grounds during migration, using different indicators. The study revealed that blue whales prefer feeding in deeper waters, areas with krill abundance, cooler water temperatures, and underwater landscapes that attract more prey.

“The information in this work results from more than five years of effort, sailing thousands of miles and spending hundreds of hours doing fieldwork in various conditions. Captain Yuri played a crucial role in this collaborative effort, and his skill and ability made it possible to safely and efficiently approach the largest animal on the planet,” said STRI staff scientist Hector Guzman, the paper's lead author.

By integrating data from these tags, the researchers aimed to understand how these factors influence the migratory and foraging behavior of blue whales. It was previously thought that they used the Galapagos during the cooler seasons (austral winter and spring) for breeding and returned to their southern feeding grounds off Chile and Peru during the austral summer. However, occasional sightings of blue whales in the Galapagos during the warmer season indicated a year-round presence.

Their findings suggest that most of the tagged whales remained in the Galapagos, particularly near Isabela Island, which is increasingly frequented by tourist vessels. However, they could not definitively confirm continuous presence year-round. Some whales ventured into mainland Ecuadorian waters, and one even traveled to Peru.

Hector Guzman, STRI staff scientist and lead author.

Credit: Fernando Rivera

This data underscores the significance of the Galapagos Archipelago as a critical foraging area for the species. “Our research, which applies advanced behavioral models, reveals the intricate connections between blue whales' migratory behavior and their ocean environment. It highlights the critical habitats these giants depend on and the importance of scientific insights for their conservation,” said co-author Rocio Estevez.

The study highlights the importance of understanding blue whale migratory and foraging patterns to inform conservation strategies, including protecting critical foraging grounds that provide consistent food resources and shelter for breeding. As climate change and El Niño events alter chlorophyll, primary productivity, and water temperature, blue whales may need to adapt their migratory and foraging behaviors. This adaptability suggests a need for dynamic conservation measures that can respond to shifting environmental conditions.

To reduce collision risks in the Galapagos, it is essential to implement measures that mitigate ship strikes, such as limiting the number of tourist boats or their proximity to whales, establishing shipping lanes, and enforcing seasonal speed restrictions in critical habitats. As awareness of the importance of healthy oceans grows, protecting biodiversity and its vital ecosystem services, such as food provisioning and carbon sequestration, has become crucial for maintaining ecosystem stability and resilience.

“The first time I maneuvered a small inflatable boat with Hector to tag whales, I had mixed feelings, fear and joy, until the moment came, and it was an experience I could not find words to describe. It was a wonderful experience, and I learned to appreciate these giants of the ocean,” commented Captain Yuri Revelo.

Smithsonian science helps understand blue whale migratory and feeding patterns to inform conservation strategies with new study, the first to satellite-tag blue whales in the Galapagos.

Credit:Image courtesy of Rodrigo Hucke-Gaete

The authors thank the Government of Ecuador, the Galapagos Park Service, and the Galapagos Science Center (Universidad San Francisco de Quito – Daniela Alarcon) for providing the research permits and institutional administrative support. They gratefully acknowledge Captain Yuri and the crew of the FV Yualka II. They also thank Jenifer Suarez, Daniela Alarcon, Roberto Velasquez, and Fernando Rivera for institutional and field assistance.

This research was funded by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the Isla Secas Foundation, the Anne Page Chiapella Family, and the Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (SNI) from Panama's National Secretariat of Science, Technology, and Innovation (SENACYT).

Reference:

Guzman, Hector M., Estévez, Rocío M., and Kaiser, Stefanie. 2024. "Insights into Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus L.) Population Movements in the Galapagos Archipelago and Southeast Pacific." Animals, 14, (18). https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14182707.