New tools

New fossil catfish species identified through 3D visualization technology

Through the use of new tools and techniques, paleontologists can better advance our understanding of the paleodiversity of different geological periods

Despite the abundance of well-preserved Ariidae catfish fossil fragments from the Neogene Period (23 million to 2.6 million years ago) in the Americas, a majority of them remain unidentified in museum collections. That is, paleontologists have placed them within the Ariidae family, but the exact species remain undetermined. Addressing the need for more accurate species identifications, scientists from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and collaborating institutions employed modern technologies to analyze these fossil catfish skeletons and classify them.

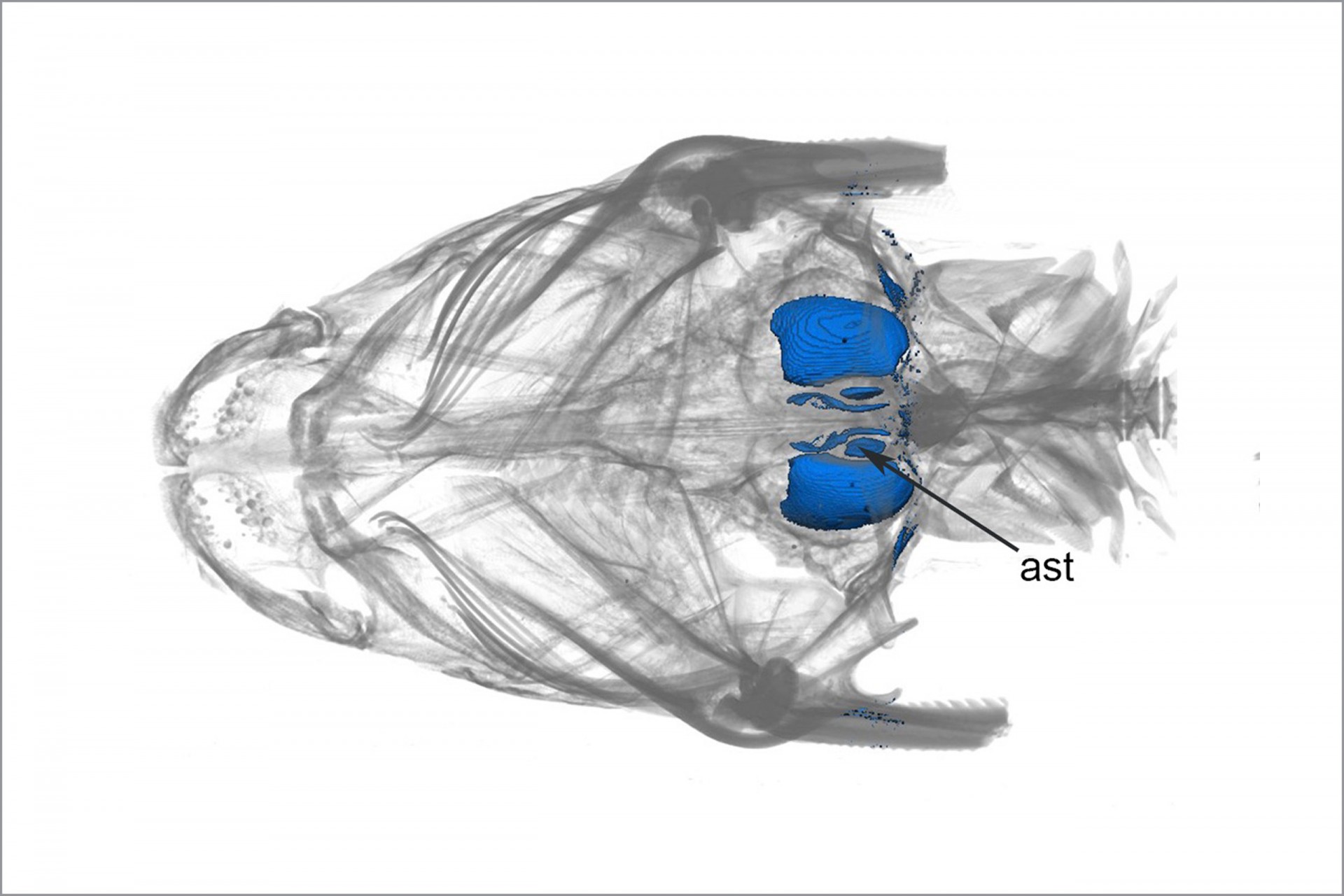

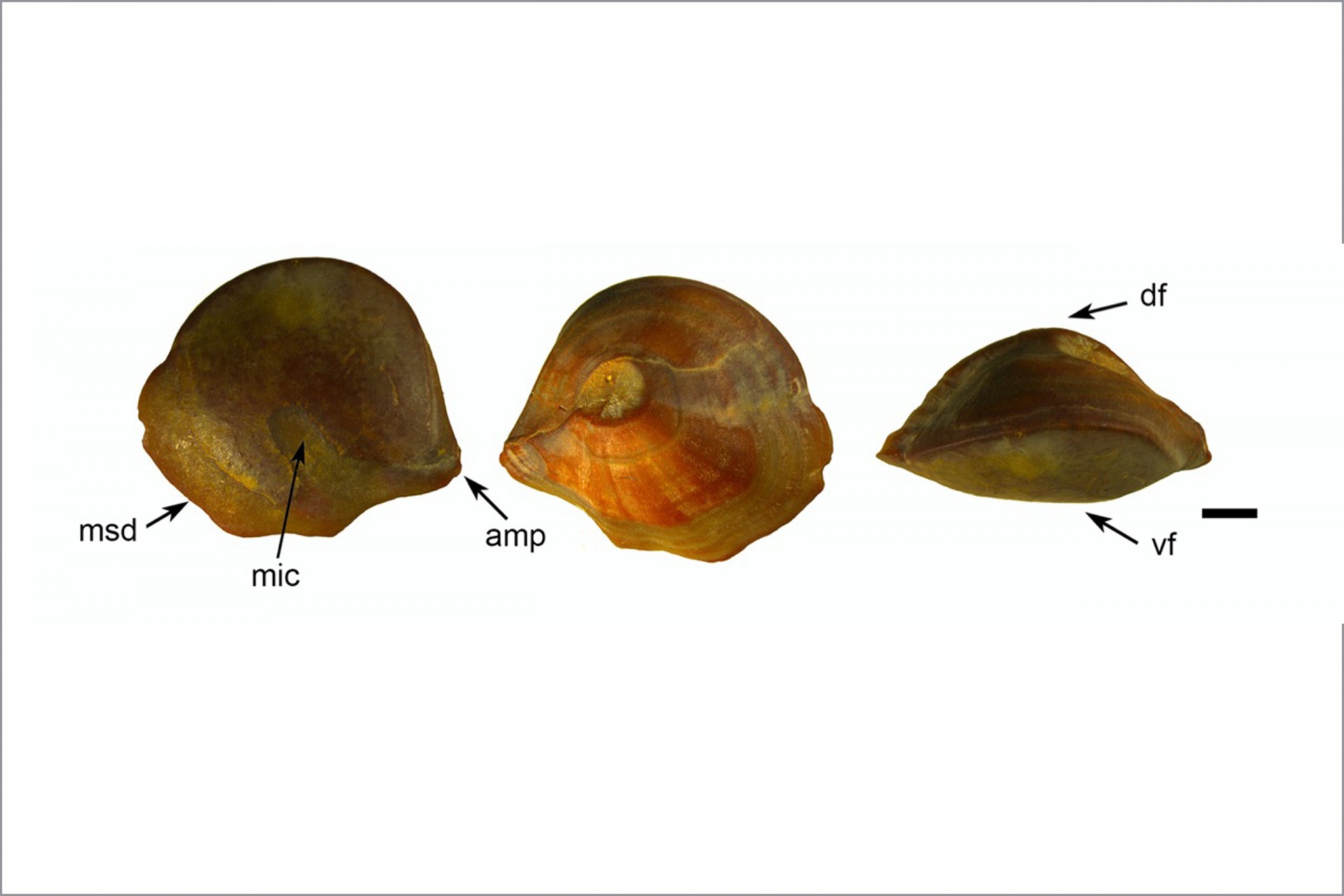

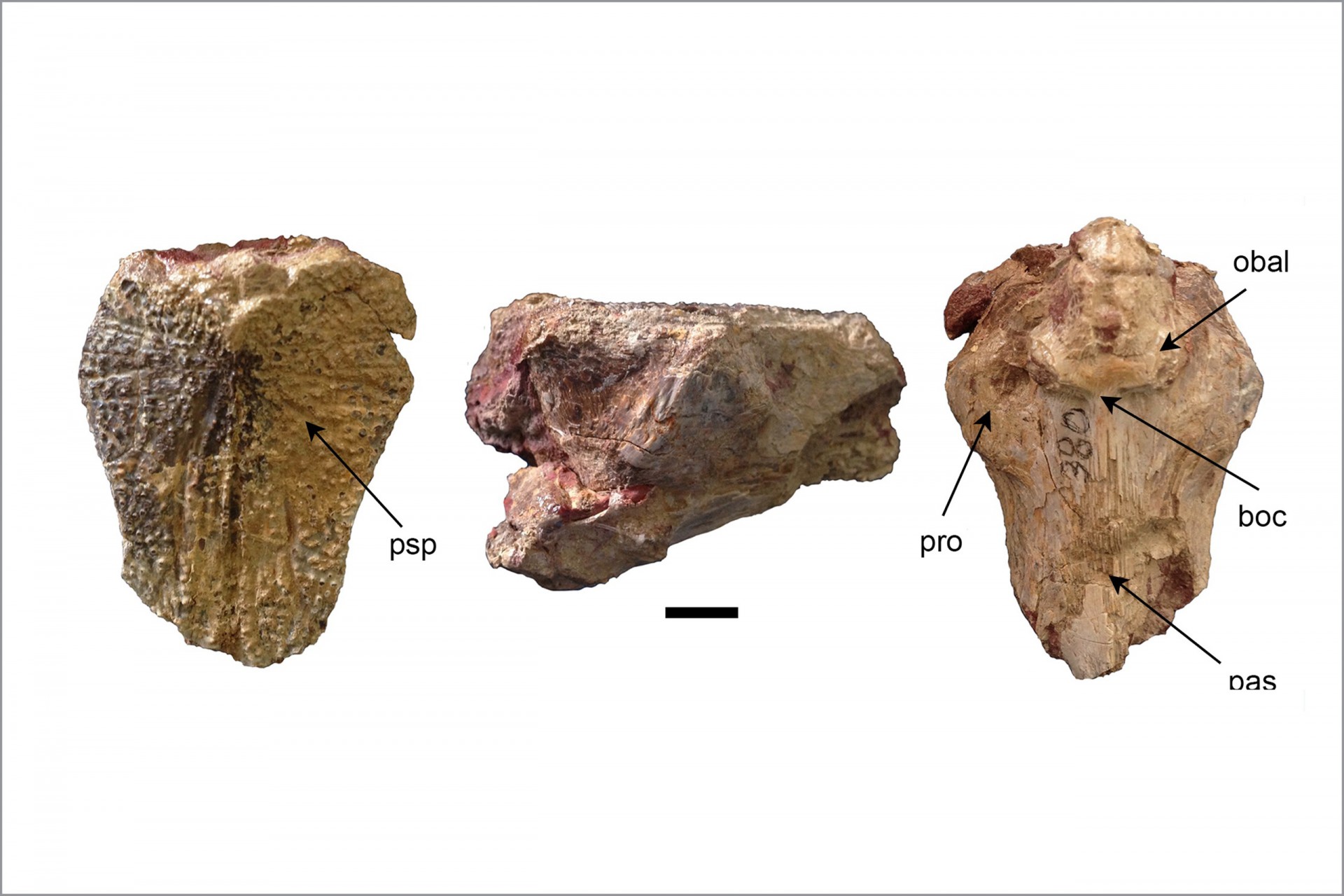

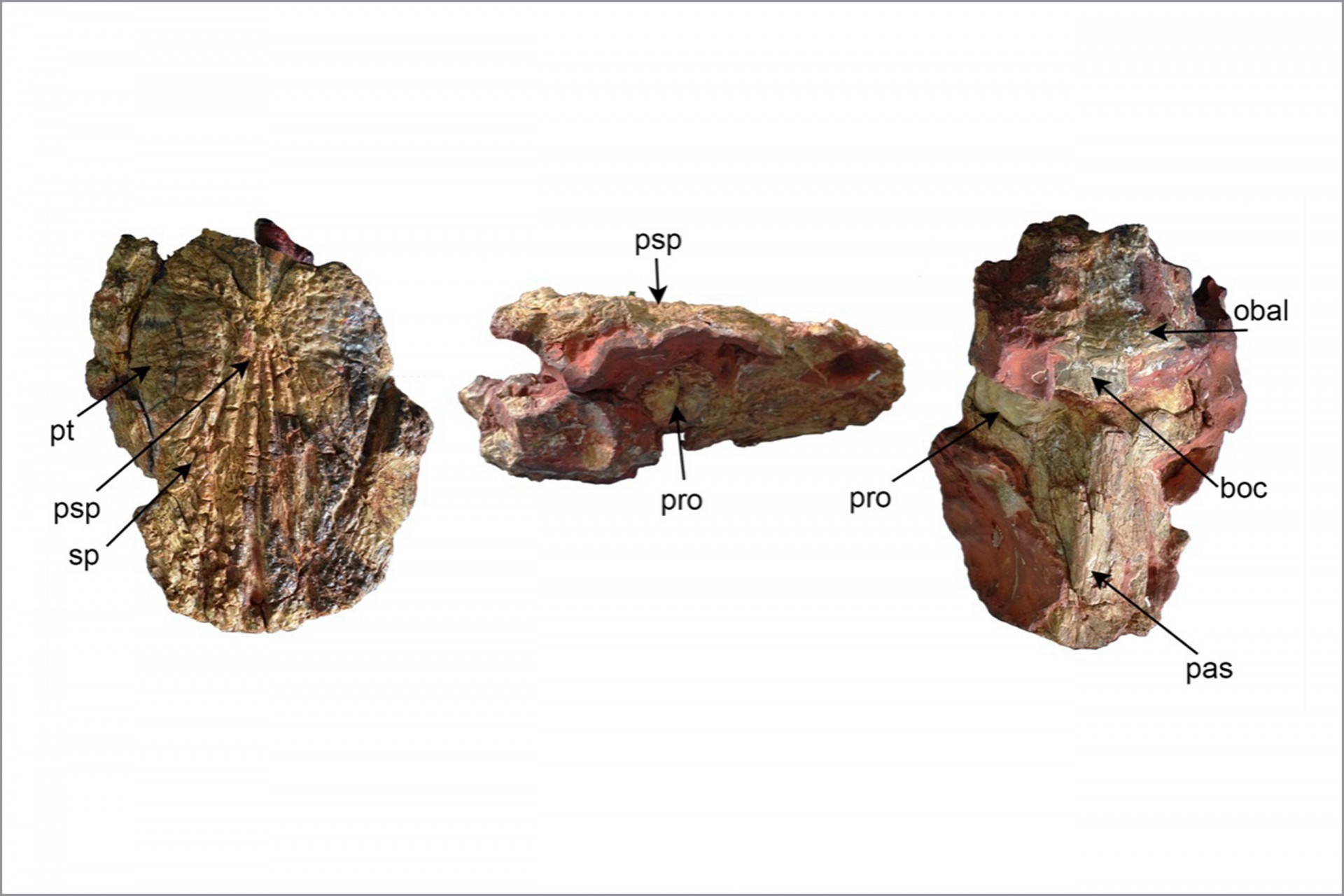

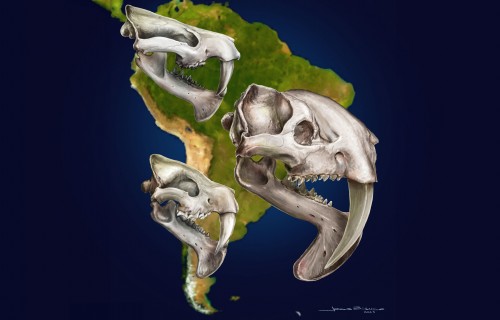

Bony fish species, such as catfish, have otoliths or inner-ear bones. In the absence of other fossil structures, researchers may use these calcium carbonate structures of distinct shapes and sizes to identify species. However, traditional paleontological techniques employed for these purposes only go so far. With the help of a high-resolution scan imaging technology called micro-CT, the research team produced a series of 3D images from catfish fossil fragments –including skulls and otoliths– found in various museum collections and formations in Venezuela. This allowed them to recognize certain anatomical patterns and internal structures, and to provide specific taxonomical classifications.

“Otoliths are like fingerprints in humans, so all fish families can be identified by their otoliths, which are extremely abundant in the fossil record,” said co-author Félix Rodríguez, STRI paleontologist and scientific coordination assistant. “On the other hand, the study of comparative anatomy, using the skulls of Ariidae and contrasting them to the fossils in different museums, made possible the reconstruction of the analyzed material. Without a doubt, these types of investigations are only possible through multidisciplinary and interinstitutional collaborations.”

The scientists not only identified the Ariidae catfish species collected from Venezuelan formations and re-classified museum collections, they also described some new species, and reconstructed the time sequence (in millions of years) of the Ariidae family inhabiting the ancient estuarine system in the south proto-Caribbean Sea (before the emergence of the isthmus of Panama). The species descriptions, as well as the 3D reconstructions, digital photos, skeletons and other tools used to produce them were recently published in the Journal of South American Earth Sciences.

“micro-CT has been used for a few years in paleontology with very good results,” Rodríguez said. “We demonstrate it in this study, by describing two new fossil catfish species (Ariopsis castilloensi and Bagres ornatus), determining for the first time the internal morphology of four fossil catfish skulls, and reporting the first fossil record of Bagre marinus in Venezuela.”

For the team, this work highlights the importance of caring for well-preserved, isolated fossil remains for taxonomic purposes, as well as the value of multidisciplinary alliances and the incorporation of new tools and techniques for advancing our understanding of the paleodiversity, paleoenvironment and paleogeography of different geological periods.

“The use of three-dimensional digital renderings of extant and fossil skull bones and otolith reconstructions, for the identification of fossil catfish, provides a good baseline for the recognition of other undescribed museum specimens waiting for accurate identification,” said Orangel Aguilera, tenured professor at the Marine Biology Department of the Federal Fluminense University in Brazil and main author of the study.