Marine resource use has influenced human population on the Central American Isthmus for millennia

New

artifacts

More gold,

less Surfer's Ear

Text by Leila Nilipour

A bony growth among the remains of Paleoindians from the Gulf of Panama reflects changes in their cultural activities over time

Vanessa Sánchez was interested in bones when she migrated from Venezuela and enrolled in the anthropology school at the University of Panama. Back home, she had done osteological studies, as she toyed with the idea of studying medicine and archaeology concurrently. Once settled in the isthmus, she resumed her fascination with skeletal remains.

As soon as she arrived, she found out that bioarchaeologist Nicole Smith-Guzman was developing the kinds of projects she was interested in at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), in archaeologist Richard Cooke’s lab. She first joined as an intern, three years ago. And this year, she did a short-term fellowship to conduct research for her undergraduate thesis.

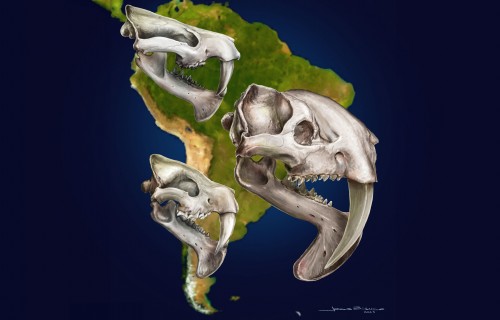

She focused on “Surfer's Ear” or external auditory exostosis, a common condition among ancient Panamanian populations living near the Gulf of Panama. This bony growth in the ear canal results from the constant exposure to the wind and cold water.

Based on analyses of early bone remains, Smith-Guzman and Cooke concluded that this was associated with the exploitation of marine resources by Paleoindians, especially during the coastal upwelling season, when the water temperatures in the Gulf of Panama drop significantly.

So, Sánchez wondered, would the prevalence of this condition decrease in more recent remains, when Paleoindians started valuing gold over shell artifacts? After checking all the skulls, she found no evidence of Surfer’s Ear in those dating after 800 AD.

“This demonstrated the hypothesis that they were engaging in activities other than the exploitation of marine resources after that date”, Sánchez explains.

That is, although they were still diving to extract seashells in the Pacific, they were not doing it as intensively as before 800 AD. This finding reinforced the hypothesis of archaeologists like Cooke who, based on analyses of the material culture of these human groups, proposed that the search for seashells was an industrial activity on the coast of the Gulf of Panama before this date.

For Sanchez, STRI’s internship and fellowship opportunities have been crucial in her career.

“The Smithsonian has allowed me to develop professionally and experience how scientists work. Without the financial aid, I would not have been able to do any research, because I would have had to find a job that would have taken me away from bioarchaeology”, Sánchez concludes.