Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Frog

fertility

clinic

Artificial fertilization key to rescuing Panama’s endangered frogs from extinction

Text and photos by Beth King

Cover by Steven Paton

Animals in captivity may have trouble breeding, so to keep amphibian species from dying out, researchers are discovering new ways to help them reproduce.

In the Noah’s Ark story, Noah rescues pairs of every creature on Earth from a devastating flood. He makes it look easy. But it took Gina Della Togna, research associate at the Smithsonian’s Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project (PARC) and her collaborators, years to artificially fertilize harlequin frogs successfully in captivity: a huge leap forward in the conservation of these endangered species.

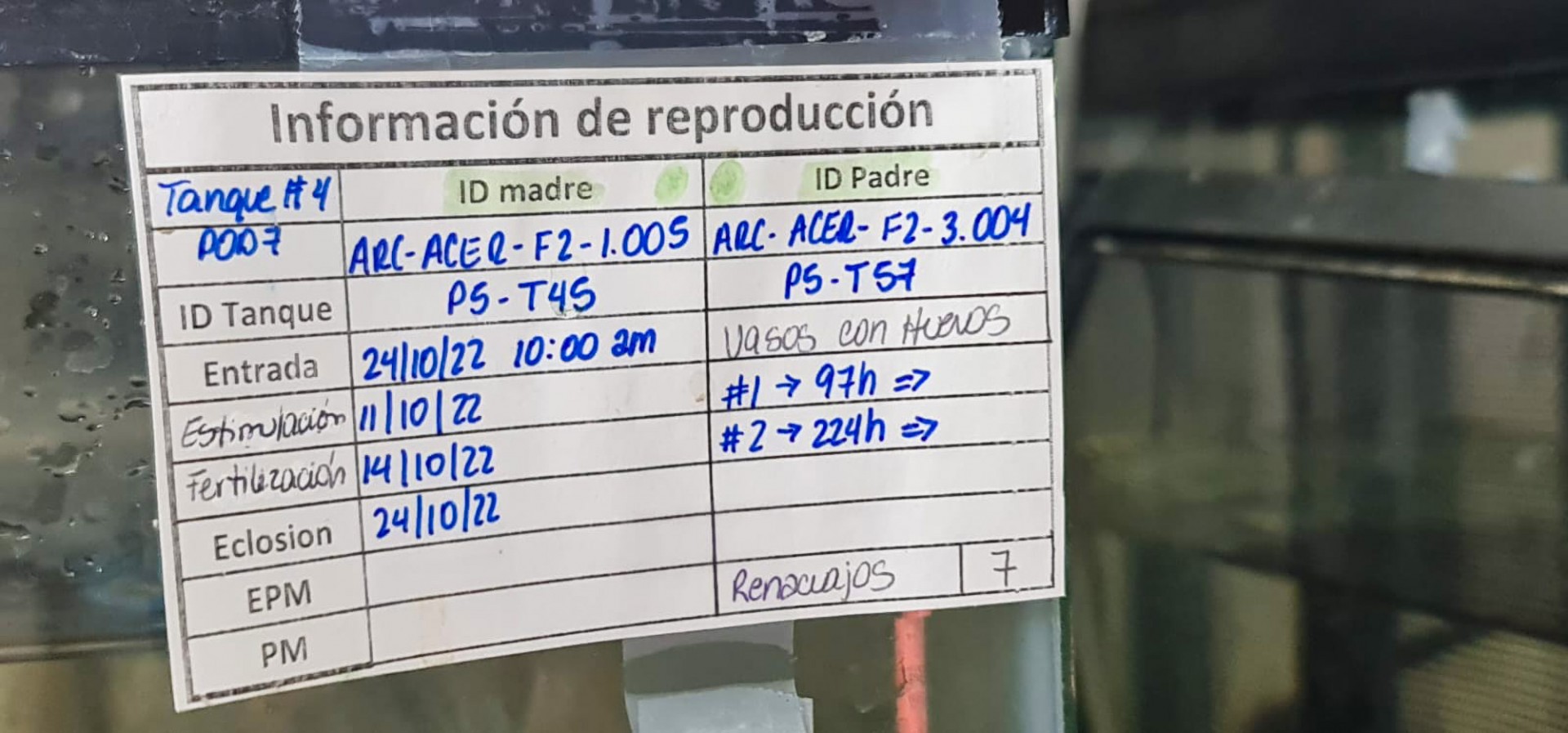

Zookeepers struggle to recreate the conditions wild animals need to breed. In the case of the 12 endangered frog species living in shipping containers at the PARC rescue center in Gamboa, Panama, researchers recreate bubbling mountain streams in terrariums, and dedicate a whole shipping container to raising fruit flies, crickets, and other insect food to keep the frogs alive.

STRI Research Associate, Gina Della Togna, and Jorge Guerrel, PARC project program manager, working in the Gamboa, Panama, rescue center to fertilize frog eggs.

Frog habitats in captivity are very different from their habitats in the wild. We know little about mating in the wild, frog diets, or what conditions are best for the survival of eggs, tadpoles and adults.

Their biggest success to date is with the variable harlequin frog Atelopus varius. Thirty of the original frogs they rescued from the wild are still alive, and a dozen pairs of frogs are breeding successfully. So now they have about 500 frogs of this species, including all the offspring, enough to try the next step: releasing them back into the wild and hoping that they won’t be killed by the chytrid fungal disease that is wiping out frogs and other amphibians around the world.

One of the lead biologists on the PARC project, Della Togna, after finishing her undergraduate degree at the University of Panama, completed her doctorate in cellular and molecular biology at the University of Maryland in the US with a grant from Panama’s Office of Science, Technology and Innovation (SENACYT). First, she developed hormonal stimulation methods to obtain high quality sperm from Panamanian golden frogs (Atelopus zeteki), then she developed methods to freeze (cryopreserve) Panamanian Golden Frog sperm. During her postdoctoral training, she expanded her research to six more amphibian species with the goal to help improve the reproductive success of these endangered species. In 2016, she returned to Panama and is currently a STRI research associate. For the last several years she has been discovering the right conditions to stimulate females to lay eggs, and to fertilize them under the best conditions for their development.

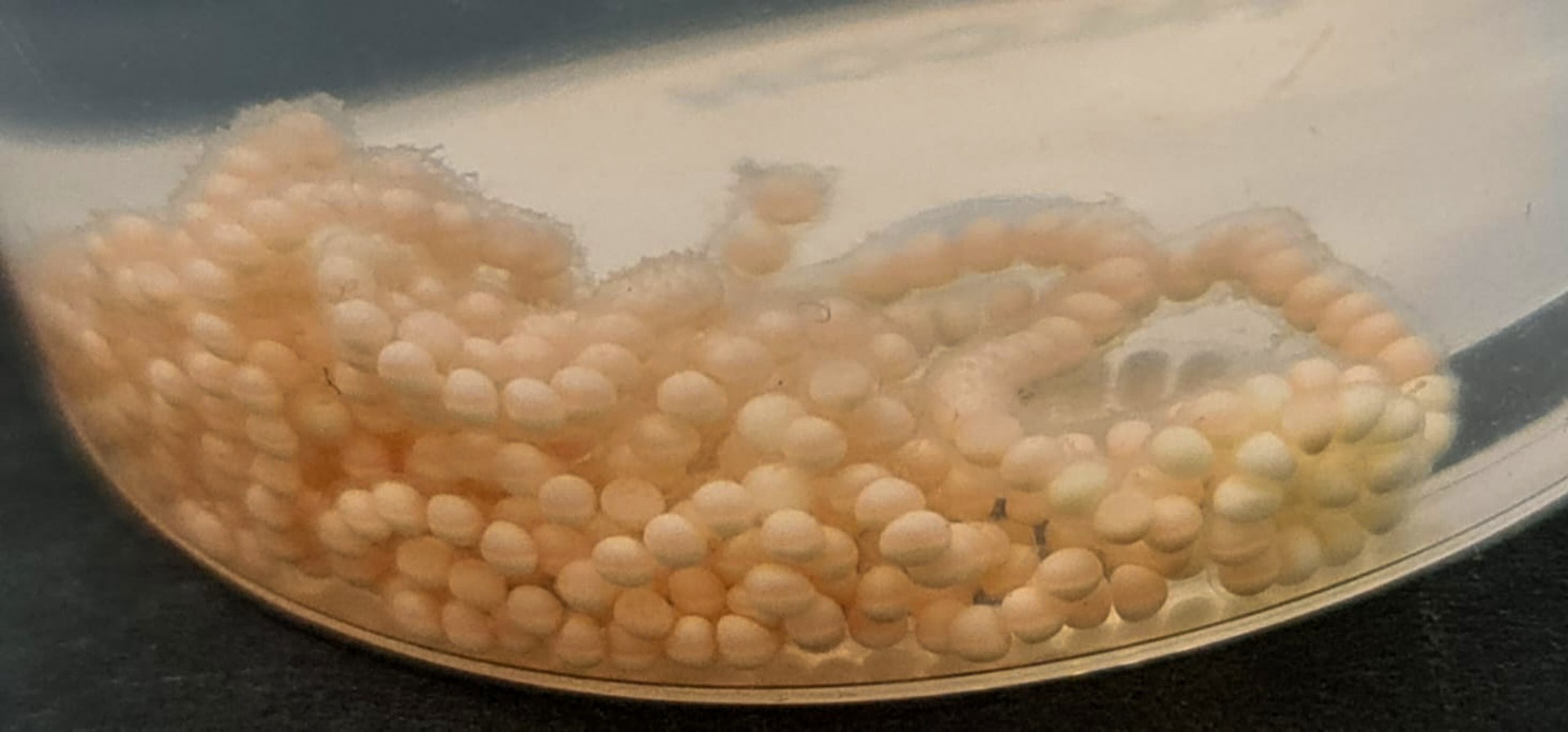

Artificial fertilization will result in hundreds of extra frogs to release. Each female makes about 2500 eggs. Gina stimulates the Atelopus varius and Atelopus certus females with exogenous hormones to lay about 350 eggs at a time in a petri plate over a period of 7-10 hours. The tiny eggs look like long strands of pale pink pearls. On the same day, before stimulating the females, she stimulates males to produce sperm in their urine, followed by collection and characterization of the samples to assess their quality, which depends on the age, health, and well-being of each animal.

It is easiest to use a phone or camera to photograph eggs through a microscope lens and then look carefully to see if they have changed shape.

Unfertilized eggs are round, whereas fertilized eggs are hamburger shaped.

This time she uses sperm from two different males to increase the genetic diversity of the offspring, which will maximize the use of healthy eggs laid by a single female. This technique will allow researchers to use several different males at a time and to improve the genetic management of the offspring and captive population.

Gina strips the strands of eggs from the mother, fertilizes them with the sperm and places them in the dark. By the third day after fertilization, some of the eggs begin to change shape from perfectly round pearls to a hamburger like shape—these give Gina hope, because they are probably fertilized. Because this species of harlequin frogs usually lay their eggs in swiftly flowing streams, she bubbles the water with oxygen.

Five days after fertilization, it is easy to see which eggs are developing to contain small, white tadpoles. And finally, ten or twelve days after fertilization, they hatch.

“One of the reasons that I’m really thrilled with this is that we could fertilized a single female with sperm from 10 different males, which would really speed up our ability to create genetically diverse frog populations”.

Fertilization has to happen at a very precise moment after the eggs are laid, and it was difficult to work on this during the Covid 19 pandemic because researchers were spending less time in Gamboa at the PARC facility. Gina remembers speeding out to Gamboa in her car, while giving step-by-step directions to Brian Gratwicke, from the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, who was there at the exact moment when fertilization needed to take place.

“It’s really like a human fertility clinic. First we optimize the hormone treatments for males, then we optimize artificial fertilization protocols, and the cryopreservation protocols,” Gina said.

Gina holding a plastic container, home to one of only a few frogs of this species, raised in captivity.

Adult harlequin frog, Atelopus certus.

There is a huge gap between the idea of captive breeding and turning it into a reality: Gina is closing the gap. Every small victory contributes to the potential to release these species back into the wild. Gina managed to produce tadpoles of Atelopus certus, the Toad Mountain harlequin frog, which only exists in Panama and nowhere else on Earth.

“Now it seems really easy, but it was tough to get to this point.”

Why are these frogs important? Gratwicke, who co-directs the project with STRI’s Roberto Ibañez, says that for him, this is an emotional, rather than a scientific question: “…when the forest loses its nocturnal soundtrack it becomes a poorer place…” he wrote in a paper last year.