Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Following

the swarm

Making a short documentary film in Panama’s tropical forest

Text by Olivia Milloway

In the Panamanian forest, researchers track swarms of carnivorous army ants and the birds that follow them. A new documentary reveals a glimpse of life, and research in the Neotropics

In the early morning light just a few miles from the Panama Canal, a colony of army ants march one by one from their nest. They move slowly, even lazily, as if rubbing the sleep from their eyes as they stumble off to their early-morning shifts. Abruptly, their pace quickens, their grogginess replaced with urgency. The day’s raid had begun.

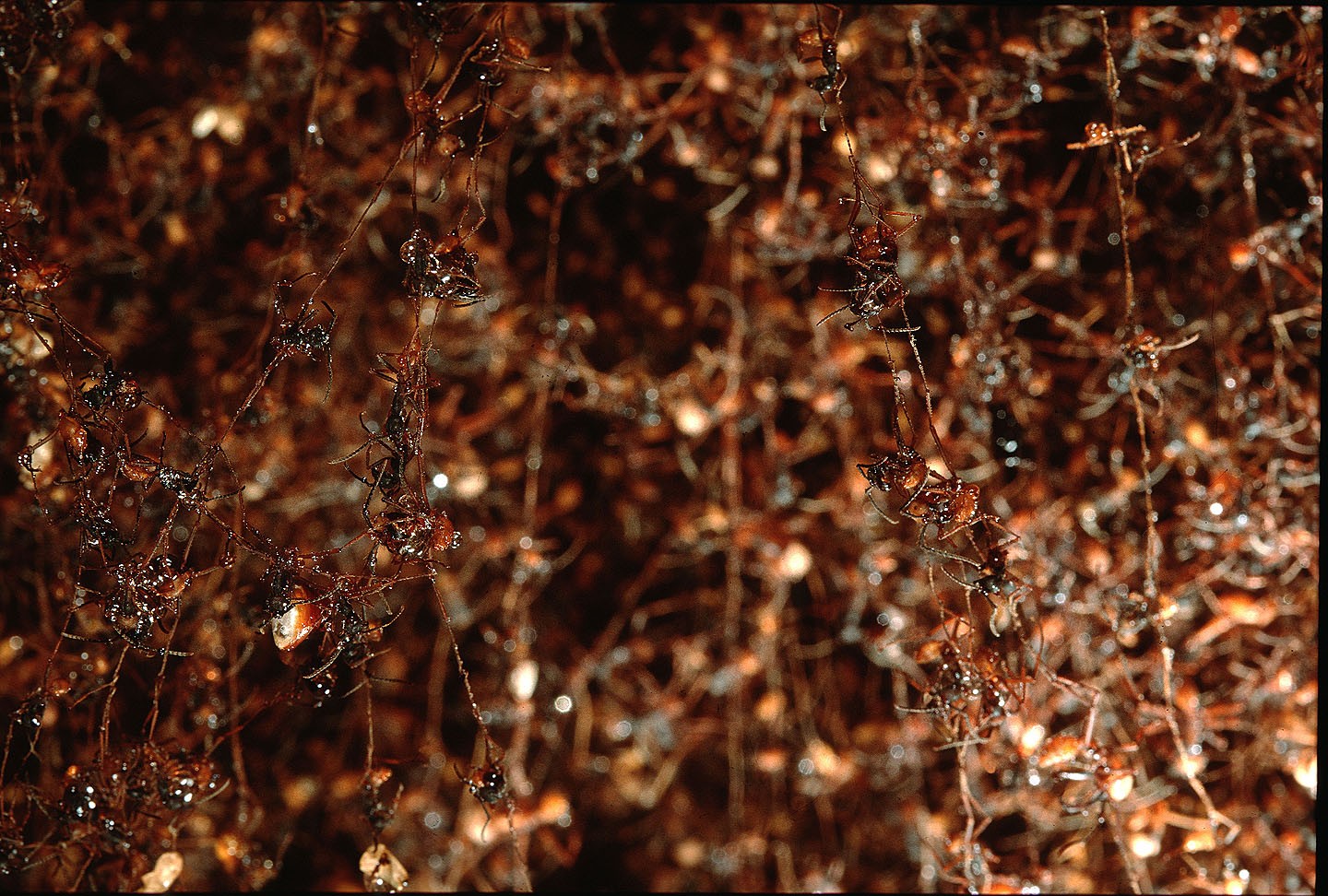

The name “army ants” refers to more than 200 species of carnivorous and nomadic ants found in Central America, South America, and Africa. They band together in swarms up to 200,000 strong and hunt for spiders, crickets, and other arthropods. Once they locate their next meal, the ants pile on their prey, ripping it limb from limb and carrying it back to their nest. Others make mobile nests out of their own bodies. These bivouacs, which shelter the queen, larvae, and eggs, can be picked up and moved quickly when the ants need to search for food.

This particular species of army ants, Eciton burchellii, is the lynchpin behind the largest known animal association; over 500 species have been documented to associate with army ant swarms, relying on them at least in part for their survival. Some of these associates are kleptoparasitism, meaning they feed on the insects fleeing from army ant swarms. Kleptoparasitism – coming from the Greek terms for “thief” and “one who eats at the table of another” – is common around ant swarms among clever birds, lizards, and even fish who rely on army ants to do their dirty work. But there are even stranger ways species have evolved to take advantage of army ant swarms: some butterflies feed exclusively on the poop of army ant-following birds, while some parasitic flies lay their eggs in the bodies of fleeing insects.

“It’s a common phenomenon, but I haven't seen many attempts that capture both sides of the story. When [ant swarms] are covered, the ants are portrayed as a force of destruction. But they’re providing critical opportunities for these birds,” explained videographer Joseph See.

While growing up in California, Joe became interested in tropical biology while watching classically narrated nature documentaries. Joe came to the tropics seven years ago to work as a biologist, bringing along a camera on his field expeditions just for fun. But over time, Joe became drawn to science communication. “I always thought that the implications of the research were the most important part, and I saw how videography could move people towards conservation, like it moved me.”

At the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Gamboa, Panama, doctoral researcher Mary De Aquino leads a team of technicians and undergraduates from the University of Wyoming in studying Eciton burchellii as a part of the army-ant-followers project. Mary generously offered to let us tag along in the field, so with Joe’s camera and my microphone in tow, we followed the team as they tracked down the ant swarm.

The site was a flurry of activity: the thousands of ants moved as one with no leader in sight. Tendrils of ants branched off the main group, climbing up trees in search of prey or natural catwalks to cross the stream. Finding no such routes, the ants made short bridges out of their own bodies, a phenomenon called self-assembly. Meanwhile, the birds pounced down from their perches in the canopy, sometimes fighting over fleeing bugs. The researchers moved around the perimeter of the swarm, tracking its progress while documenting the birds’ behavior.

Joe crouched low to the ground, his camera recording a timelapse of the ants disassembling a cricket to take back to the bivouac. I lowered my microphone to pick up the crunching sound of the ants marching across leaves. We held still against the forest floor, getting stung, hard.

With the researchers’ help, Joe told me he learned how to “think like an ant.” “When you’re a photographer, you want to be there the second the action happens. To be a videographer, you have to learn to predict the future, where the ants will be in a few minutes so I have time to set up the perfect shot and be in the action. The ants might bite you like crazy, but you have to let them come to you.”

Juggling different tasks in the field – tracking the swarm, making behavioral observations, and leading her team – Mary sometimes misses the finer details in the forest that Joe was able to catch on film. “Joe shared a clip of a bicolored antbird with an ant in its bill and rubbing in on its feathers. That’s called anting, which I had read about but had never actually seen at a swarm.” she said. “It was really cool for me to finally see it, and see it captured so beautifully and artistically.”

"Anting" describes the behavior of birds rubbing objects, frequently ants, on their feathers and skin. While the exact purpose of anting is unknown, one hypothesis is that the chemicals secreted by insects could help get rid of or deter parasites.

Credit: Joseph See

Michael Castaño, a master’s student on the army-ant-followers project, emphasized the importance of studying how species interact. He said that in the past, scientists worked to understand and conserve specific charismatic species; think bald eagles, grizzly bears, or lions. Army ants don’t typically fall into that category. “Today, species are becoming extinct at an alarming rate – more than thirteen times what’s normal. We’ve realized we need to change our approach to conservation away from just focusing on individual species,” Michael said. Mary explained it this way: “If you have a species of conservation concern, you can't just focus on that species. You have to know, where does it nest? What food does it eat? How does it rely on other species for survival?”

To Joe, nature videography is a way to inspire people to care about the natural world, especially in the often threatened but critically important tropical forests. “Video, as a medium, allows you to tell a more complex story in a way that the viewer can put it all together for themselves. Now that taking videos is becoming more accessible, we’re seeing more diverse storylines and storytellers in wildlife videography.”

Mary sees potential in committing army ant swarms to film. “I hope this story will captivate others, and share a bit of the feeling of awe I first felt when I first saw an army ant swarm.”

Credit: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute

Mary De Aquino is a second year PhD student at the University of Wyoming in the Program in Ecology and Evolution in the Tarwater Avian Ecology and Behavior Lab. She’s back in Panama with a new crew for another field season, this time she’s using nets to temporarily remove species from ant swarms to see how the communities are impacted.

Michael Castaño is a master’s student at the University of Wyoming in the Kelley Behavioral Complexity Lab from Medellín, Colombia. This field season, he’s tracking mixed-species flocks at army swarms to learn out how they come about. He plans to graduate in spring of 2025 and pursue a PhD in participatory science.

Joseph See is a videographer and video consultant currently living in Gamboa, Panamá. He is the Videography Coordinator for both the Amazon Research and Conservation Collective and Neotropical Science and is a freelancer. You can find more of Joe’s videography on Instagram @musingsofjoe. He can be reached at josephsolomonsee@gmail.com.