Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Can’t

hear you!

Dolphin-Watching affects

whistle frequency modulation

in bottlenose dolphins

Text by Sonia Tejada

Picture this: What to do at a party when you try to carry on a conversation, but the music is too loud? A Panamanian doctoral student is trying to figure out how dolphins communicate underwater during heavy boat traffic in the Bocas del Toro Archipelago.

Most bottlenose dolphins in the world are not endangered, but an isolated and genetically distinct population of about 70 animals in the western Caribbean of Panama is threatened by dolphin-watching, one of the main tourist attractions in Dolphin Bay, located in the archipelago of Bocas del Toro. Betzi Perez-Ortega, a Panamanian doctoral student at McGill University and fellow at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), studies dolphin sounds as she develops strategies to reduce the impact of tourism.

Bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) produce echolocation clicks to navigate and locate food. They also produce social sounds such as whistles, calls, screams, barks, pops and quacks when communicating with each other, whistles being the most studied sounds. Whistles help in group cohesion and communication between mother and calf pairs. Dolphins also use whistles as a greeting signal when meeting other groups of dolphins in the wild.

Bottlenose dolphins can modify the frequencies of their whistles and behavior in response to different acoustic environments. This ability has been widely documented in coastal dolphin populations where the acoustic environment is often dominated by small boats, producing sounds (2-10 kilohertz) that overlap with the frequency range of dolphin whistles (1-20 kilohertz).

“Modulation indicates how simple or complex the information is when transmitted through a whistle. A complex frequency-modulated whistle will use a higher bandwidth than a simple whistle and therefore the information it transmits is considered to be of better quality,” Betzi Perez said. “To find out how complex the whistle is, RAVEN software is used; this software follows the outline of the whistles and automatically counts the inflection points, that is, the places where there is a change in the frequency of the whistle.”

Cynthia Peña installing one of the recorders in Bocas del Toro. Credit: Arcadio Castillo.

Throughout the Bocas del Toro archipelago, dolphins are exposed to small tour- and taxi-boat traffic. At Almirante Bay, taxi-boats use pre-established routes and schedules to transport people between the mainland and the main island; while tour-boats visit and interact with the dolphins in Dolphin Bay during the morning hours on a daily basis.

In Dolphin Bay, lack of compliance with national regulations leads to dangerous interactions between dolphins and tour-boats. Large numbers of tour-boats follow dolphins for long periods, disrupting feeding and social behaviors and sometimes injuring the animals. Mothers and their calves may become separated. Under these circumstances, dolphins are likely to become stressed and more alert. These emotional states can be detected in the modulation of the contour of their signature whistle.

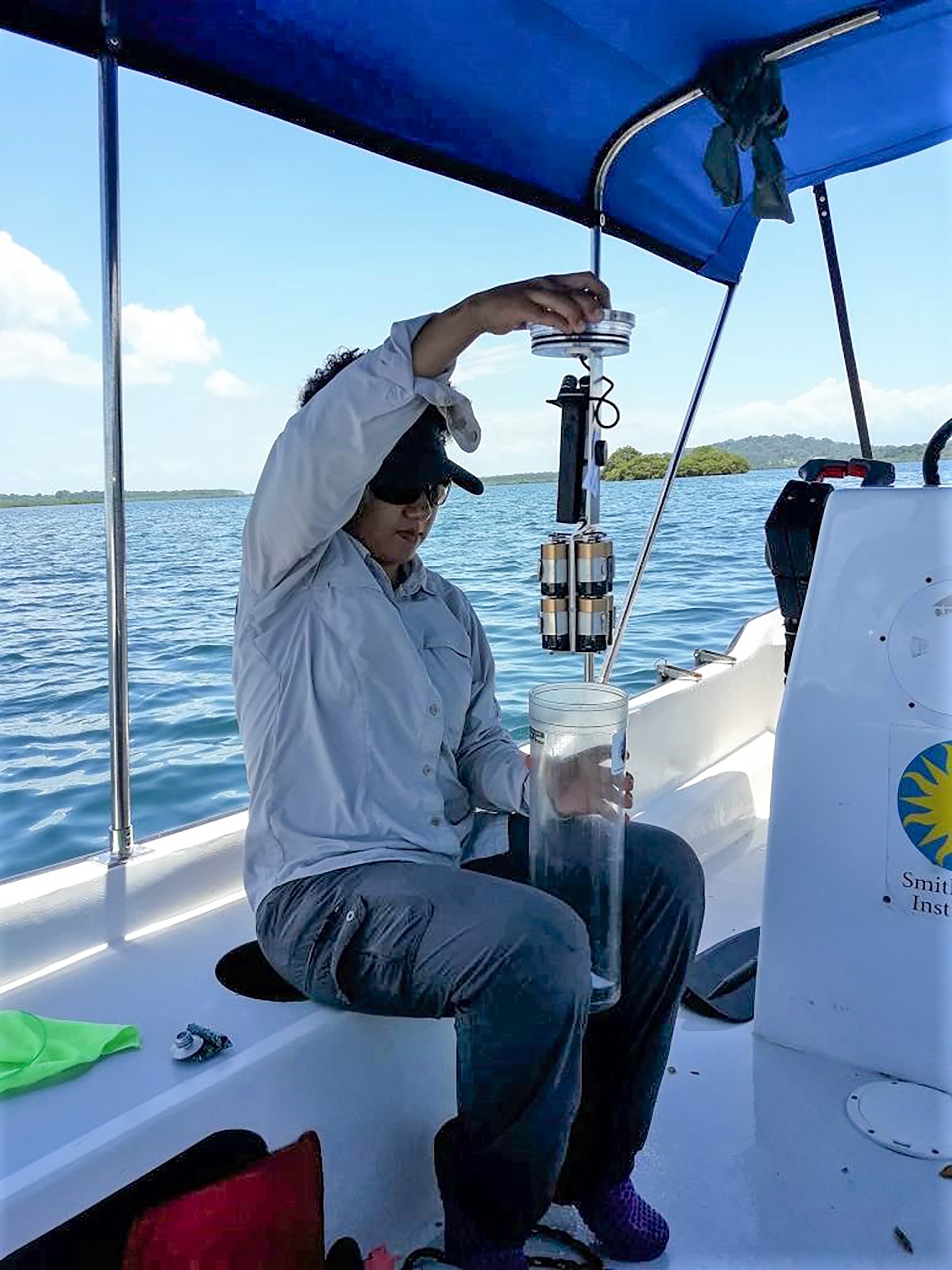

Betzi Perez with one of the recorders. Credit: Chelina Batista.

For this study, recordings were made using bottom-mounted hydrophones and an over-the-side hydrophone and a broadband recording system attached to a research boat. Perez-Ortega and colleagues analyzed almost 2000 hours of recorded dolphin sounds. Their study showed that during dolphin-tour-boat interactions, dolphins in Dolphin Bay produce whistles with an increase in frequency of ∼2–4 kilohertz, an average increase of 30 seconds in duration, and ∼9 times more modulation than the dolphin whistles recorded at Almirante Bay. This shows that in heavily transited habitats, dolphins adjust their acoustic behavior, enabling them to communicate more effectively.

These findings suggest that communication between dolphins and their emotional states would be less disrupted if tour-boat captains would behave more like taxi-boat captains, reducing contact time and intensity. These measures are required by national whale- and dolphin watching guidelines and were known to most tour boat operators.

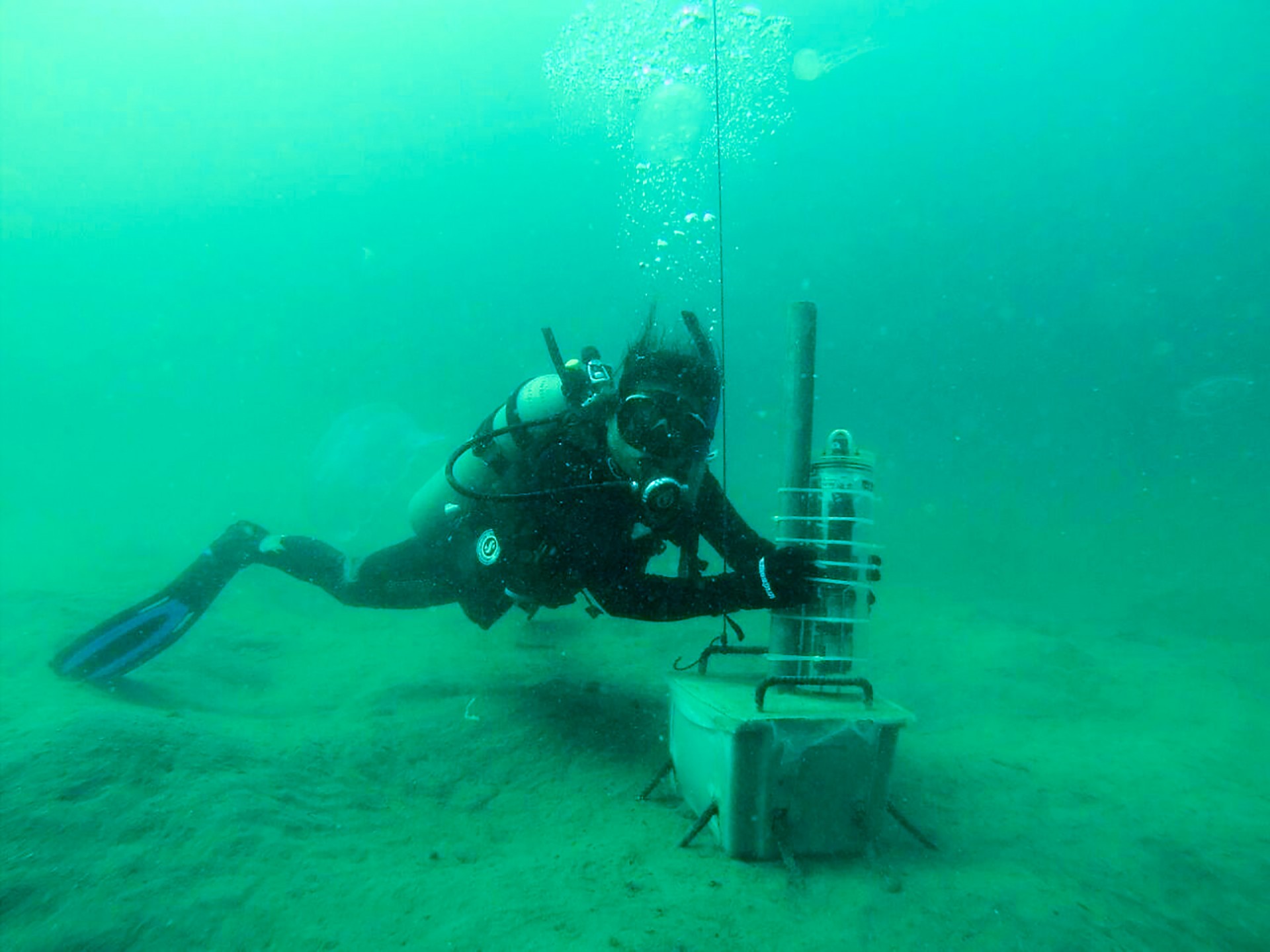

Recordings were made using bottom-mounted hydrophones. Credit: Betzi Perez.

The key to protecting these dolphins is in finding ways to effectively enforce operator guidelines.

“With this study we have been able to scientifically verify how noise affects the communication system of this species at this particular site. It becomes a starting point to think about the effect that excessive noise could be causing not only in dolphins, but also in other species that live in the different ecosystems of the Archipelago, for example, there are studies that show that noise can cause mortality in fish larvae, and it can mask the natural sounds of a reef, which are used by other species as clues to find a good place to settle,” Betzi said.

Funding for this project came from Rufford Small Grants, the ROC Grant from Waitt Foundation, the National Secretariat of Science, Technology and Innovation of Panama (SENACYT), Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), Panacetacea.org, Conservation International Costa Rica, Society for Marine Mammalogy Travel Grant, Hendry Lab, Redpath Museum and Biology Department of McGill University, May-Collado Lab and NEO-BESS Program.

Reference: Perez-Ortega B, Daw R, Paradee B, Gimbrere E and May-Collado LJ (2021) Dolphin-Watching Boats Affect Whistle Frequency Modulation in Bottlenose Dolphins. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:618420. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.618420