Above the tropical forest canopy,

sensors capture the fluxes of gases

between the trees and the atmosphere

Attachment

issues

What’s lurking

under the forest?

Text by Leila Nilipour

Photos by Jorge Alemán

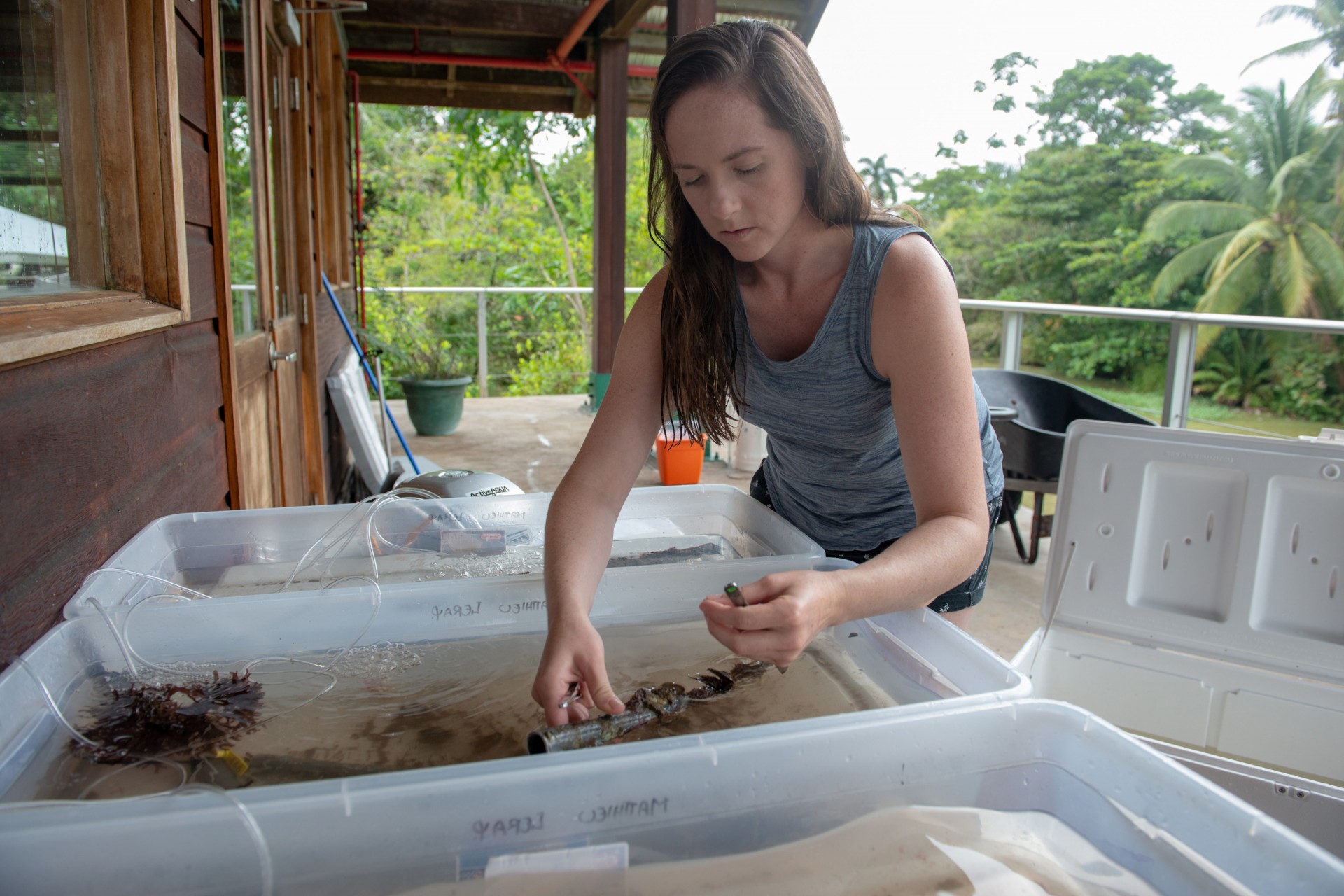

As part of her doctoral work, Heather Stewart is exploring what factors influence the marine sessile community growing on mangrove roots and what is driving the coral invasion of Bocas del Toro mangrove forests, a unique phenomenon

A thirty-minute boat ride leads us to one of the tiny mangrove islands that doctoral student Heather Stewart has chosen for her experiments in the Bocas del Toro archipelago in Panama. Some aren’t even on the map. But she baptizes them, based on their shape on satellite images.

“We’re going to Elephant Island,” she says, while steering the motorboat. Her sites were selected relatively far from the main island and ‘Bocas Town’, to reduce the likelihood of human impacts. Still, over the course of three years, she has lost three of her sites to development projects, the main cause for mangrove decline in Bocas. Onboard are her two interns, Abby Knipp and Robyn Mast. Helping Heather with her doctoral work at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) is intense. It requires many hours in the ocean followed by several more in the lab.

On Elephant Island, they jump off the boat and snorkel between the mangrove roots. Undisturbed by the many jellyfish swimming underneath her fins, Heather points out the different organisms attached to the roots. Why do they grow there? To find out, two years ago she scraped all the organisms off some roots and placed several PVC pipes among them.

This allows her to compare any new growth on both the natural and artificial structures and helps her decipher the preferences of these sessile communities: “If the organisms growing on mangrove roots just need a structure, they will also grow on the PVC pipes”.

Heather and her interns retrieve several PVC pipes that have been placed among the mangrove roots for two years, in an experiment to compare the growth of sessile communities on artificial versus natural structures.

This morning, she collects some of the PVC pipes that have been left out for two years. They’re covered in sessile organisms. Back in the lab, Heather, Abby and Robyn, measure the amount of growth on each structure and spend the rest of the afternoon identifying all the creatures to measure biodiversity.

There are sponges, tunicates, bivalves, barnacles, algae and anemones. There are even small crabs and shrimp, which are mobile, but use the intricate sessile microhabitat on the roots to hide. This will uncover how species rich an undisturbed mangrove forest can be, which serves as a comparison point for mangroves surrounding development projects.

“Sedimentation from development can choke out the roots and kill most of the organisms living there. Just because you have mangroves, doesn't mean there will be life”, Heather explains.

Hoping to gain insight into how long it may take a mangrove root community to recover from stress, Heather moved half of these PVC pipes after the first year of her experiment. Those placed in a protected bay area were switched to a wavy side of the island and vice versa, for the second year.

“Even after a year, we can see differences in the root community of those that were once moved and those that stayed. In Bocas we are protected from hurricanes, so our greatest stressor is people”, she says. “The great thing is that people can change their behavior to help the mangroves, by not cutting down trees to build, but rather building around them, not throwing garbage into the ocean or into the mangroves and slowing down when boating around the islands”.

She is also curious about a mysterious phenomenon unique to Bocas del Toro: large corals growing several meters into the mangrove forest. This has never been reported in the literature, and Heather wants to know what is causing it. Are mangroves providing a beneficial habitat?

In an unlikely phenomenon, large corals are growing several meters into the mangrove forests in Bocas del Toro, even changing their shape and color as they do, such as this brain coral.

To approach this question, she set up an experiment with fragments of individual corals collected from both the mangrove and the reef in Tranquilo Bay, a site further away from human influence. She placed some in a reef environment, which is naturally sunny, and others in a reef environment with an artificial structure that provides shade.

The other two treatments include a mangrove environment, which is normally shady, and a mangrove environment where branches have been pulled back to let the sun in. She monitors the growth and health of these tiny corals across the four treatments, to see if they fare better in one over the other.

“This will allow us to understand whether the corals grow in certain places because of the amount of light or whether it is a matter of reef versus mangrove”, Heather explains.

This is relevant because, globally, corals on the reef are being lost to bleaching. But some of those that are bleaching on the reef, many of which are more common at great depths, are thriving in the mangrove canopy here, despite how shallow it is, the high sedimentation rates, poor water quality, and large amounts of algae. Understanding the phenomenon may reveal clues to coral conservation worldwide.

And while completing her doctoral research, she aims to both minimize her impact on the ecosystem and positively influence the Bocas del Toro community. Every time she visits her study sites, she collects garbage. It is usually plastic waste, but she has recovered floor fans, televisions and even a cash register from the ocean floor.

Heather has also worked alongside the Reforestando Centroamérica initiative, raising awareness among locals about the importance of mangrove forests. For example, their role in protecting us from erosion, flooding, and storms, improving coastal water quality, protecting marine biodiversity –including juvenile species living on or around the roots, coral reefs and seagrasses– and sequestering carbon. Although Panama has lost over half of its mangrove forests and many species are at risk for extinction, in Bocas there’s still hope.

“Our mangroves are doing well and our reefs are doing much better than in other places, but there are things we can change to help protect them. That’s why it is so important to do this type of work here,” Heather concludes. “People here care about the islands and appreciate the beauty and uniqueness of this incredible place. It is our responsibility as researchers to better understand these systems and share our knowledge with others so that we all can help protect the biodiversity on this planet.”