Mutualism under pressure: new research in Panama shows a plant’s ability to keep its defender ants happy

Eastern

Tropical

Pacific

Marine expedition launched

from new Coibita station

Coiba, Panama

Story and photos by Sean Mattson

To mark the beginning of an era in marine research in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, Smithsonian scientists launched numerous long-term marine ecosystem studies in Panama’s Coiba National Park.

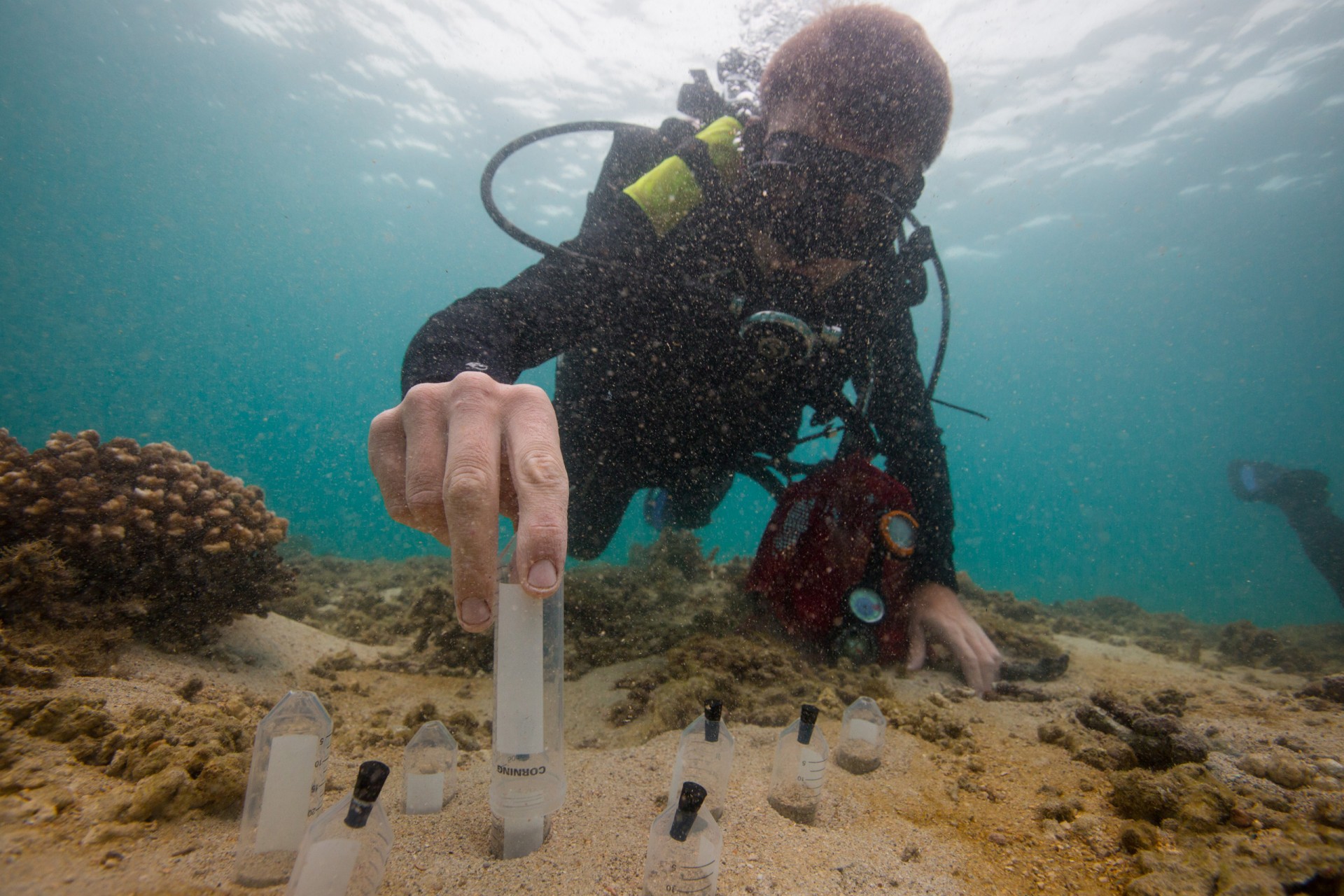

As Matthieu Leray hovers in the water above a coral reef near a remote island chain in Panama’s Pacific, he can’t see humpback whales, whale sharks or — much to his relief — massive American crocodiles from the nearby mangroves. But once he takes a few bags of water from the reef back to the lab, he may be able to tell if there were any nearby.

Thanks to new techniques that detect everything from megafauna to microbes in reef-water cocktails, the Smithsonian researcher hopes to revolutionize our concept of a healthy coral reef — and maybe even to develop an early warning system to track the changes in reefs that, until now at least, have faced much less direct human impact than other reefs around the world.

“The information you can get from a sample of water is extraordinary,” Leray says during a late-2017 expedition to Panama’s Coiba National Park, home to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s newest marine station. “You can get the signature of invasive species, characterize microbial communities involved in coral bleaching, or detect any pathogen that can damage the reef. It could be used as an alarm, if you wish, as an indicator of the potential risk to biodiversity.”

Anchored by Coiba Island — the largest Pacific island in Central America — the protected archipelago is, to some extent, a portal to a time before tropical ecosystems were radically altered by human activity.

This is especially evident beneath the waves, where coral reefs show little sign of bleaching and loss of biomass like reefs in many places around the globe. Coiba’s relatively pristine state is due to centuries of minimal human occupation: the island was a small penal colony during most of its modern history and has remained a protected park since the last prisoners were shipped off in 2004.

But Panama’s growing international profile as a tourism destination, logistics hub and foreign investment magnet has upped Coiba’s profile. Its idyllic tropical setting includes long stretches of “empty” beaches, which are an increasingly scarce global commodity coveted by resort-builders. Management plans allow some fishing and eco-tourism, and conservationists and researchers regularly wring their hands over news of “green development” plans for the area, which world-renowned conservation photographer Christian Ziegler “the crown jewel of Panama’s national parks system.”

Smithsonian scientists say Coiba is a globally relevant laboratory for understanding how healthy ecosystems should function in an era when many reefs have already undergone rapid deterioration. Keeping human impact in Coiba to a minimum is essential, they say, to discover the insights that could help improve the fate of the world’s reef systems, which are home to up to 25 percent of all known marine species.

“There’s a great number species on Coiba that are not found anywhere else on the planet, on both a terrestrial and marine level. There is an important potential for doing science that helps conservation and management of a World Heritage Site like Coiba,” says Juan Maté, the manager for scientific affairs and operations at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute who has studied Coiba’s marine ecosystems for some 30 years.

“This system continues to function at a healthy level and maintain a resilience that is not seen in many other areas.”

Maté says that the Gulf of Chiriquí., where Coiba is located, “could be a refuge from climate change,” due to its resilience to natural phenomena such as temporary ocean warming from El Niño cycles.

Smithsonian’s newest marine station

In 1998, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute was bequeathed the island of Coibita by Manoucher Mohageri, an Iranian investor and conservationist who wanted a custodian to safeguard the island’s natural state. The 242-hectare island’s ownership was contested in U.S. and Panamanian courts and a 2017 ruling by Panama’s Supreme Court finally granted ownership to STRI.

Leray and colleagues, including three more Smithsonian postdoctoral fellows and two STRI staff scientists, marked this ruling with one of the most intensive field campaigns at Coiba in many years. With Coibita’s ownership no longer in doubt, their projects will usher in a new era of tropical marine research at STRI. William Wcislo, STRI’s deputy director, likens the Coiba’s scientific potential to Barro Colorado Island, where Smithsonian scientists have built an unrivalled legacy of research on tropical forests over the last century.

“We’ve got this extraordinary opportunity here,” says Owen McMillan, a staff scientist on the expedition. “Coiba is unique from a biological perspective because the Eastern Pacific is one of the most unexplored regions of the world. Coiba is right in the center of it, in a marine corridor that starts in Mexico, goes down through Costa Rica and ends in the Galapagos islands.”

The campaign included 14 field protocols, primarily on reef and mangrove systems. In addition to collecting water for environmental DNA (eDNA) samples and microbes, the team conducted fish surveys, analyzed physiochemical water properties and took sediment cores.

MarineGEO fellow Maggie Johnson established permanent transects along 50-meter stretches of robust coral reef, where she photographed plots to track change over time and set up artificial surfaces for marine organisms to colonize. These protocols will create baseline data on which to build future expeditions and results will be directly compared with data collected by Johnson and Leray at Bocas Del Toro, STRI’s primary Caribbean station where both have collected massive amounts of data in recent years.

One area where the team is expecting breakthroughs is in the little-understood realm of microbial ecology. “Microbes are ecosystem engineers — they are invisible drivers of our visible world,” says Holly Sweat, a MarineGEO fellow who took samples from mangroves around Coiba on the expedition. “The bacteria and microalgae that are in the environment have the potential to affect the distribution and growth of larger organisms that we see all the time.”

About Coiba, says Holly, “Our world is shrinking. The more populated we become and the more shipping routes we have around the globe, remote areas are few and far between. And I think we need to hang onto the few remote regions that we have so that we can really get a good grasp of how ecosystems perform in the absence of human disturbance and that’s why this location is so valuable.”