In 2025, Panama faced the collapse of coastal upwelling, a vital phenomenon that nourishes ecosystems and fisheries. What does this mean for its environmental and social future?

You are here

Projects

& Stories

Aaron O'Dea

The natural phenomenon of upwelling, which occurs annually in the Gulf of Panama, failed for the first time on record in 2025. A study led by scientists from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) indicates that the weakening of the trade winds was the cause of this event. This finding highlights the climate’s impact on fundamental oceanic processes and the coastal communities that depend on them

In a major regional review, scientists reveal the critical interplay of biological, cultural, and environmental factors in shaping past human reliance on marine resources along the Pacific coasts of the Central American Isthmus.

A groundbreaking study of 7000-year-old exposed coral reef fossils reveals how human fishing has transformed Caribbean reef food webs: as sharks declined by 75% and fish preferred by humans became smaller, prey fish species flourished —doubling in numbers and growing larger. This unprecedented look into prehistoric reef communities shows how the loss of top predators cascaded through the entire food web, shifting the balance amongst coral reefs.

A new collaboration between STRI and the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry will make a research vessel available to researchers, educators and marine policy makers working in the Tropical Eastern Pacific.

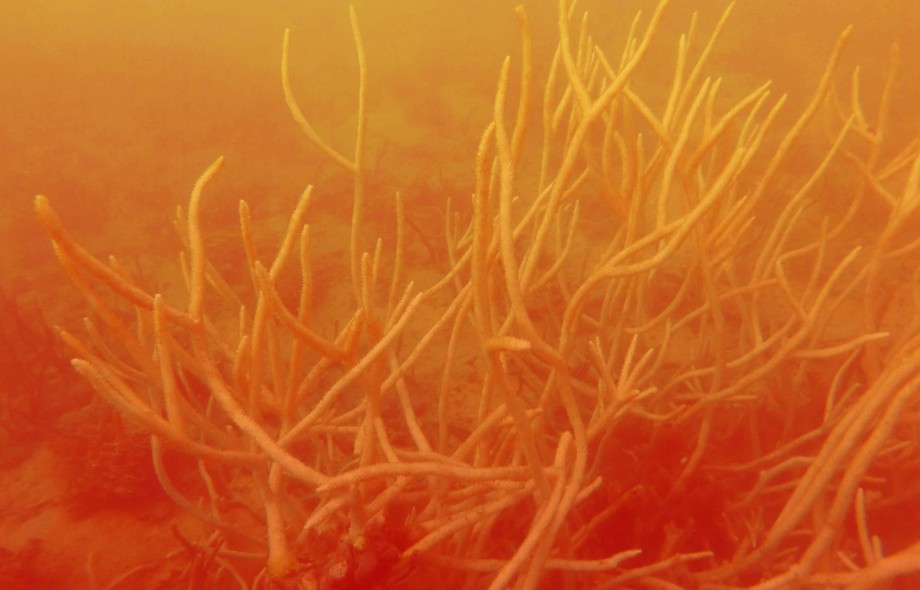

In September 2017, divers observed a massive “dead zone” rising to envelop Caribbean coral reefs in Bocas del Toro, Panama. Smithsonian post-docs joined together to understand marine hypoxia now and in the past.

Lab Members and Collaborations

Estimating shark populations on degraded Caribbean reefs is complicated, especially when there few around. A pioneering member of the O’Dea lab has developed a technique to estimate shark populations — both past and present — using their microscopic skin scales