Ask

George

Remembering George R. Angehr

(1951-2021)

Text by Beth King

Cover photo by Christian Ziegler

STRI mourns the loss of natural historian and colleague, George Angehr.

Before Google was a verb, the response to any seemingly unanswerable questions about nature in Panama that we had in the STRI communications office was a simple “Ask George.” But as of Nov. 24, 2021, one of Panama’s most brilliant and encyclopedic natural historians, George Angehr, is no longer with us. His official roles as Research Associate at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and active member of the Panama Audubon Society do not begin to describe his contributions to Panama and the world as an explorer, ornithologist, author, conservationist, scientific illustrator, museologist, guide and friend.

George is best known as co-author of Panama’s best bird guide and as a major intellectual and artistic force behind the monumental exhibits at Panama’s BioMuseo. But he was a lifer who came to Panama as a student and never left, dedicating his abundant talents to making scientific information available to everyone from school children to ambassadors.

Always happy to help, George shares a bird ID with journalist Lars Abromeit from GEO Magazine during the 2015 Bioblitz in Panama’s Coiba National Park and UNESCO World Heritage Site. Photo by C Ziegler.

A native of the Bronx (and avid New York Yankees fan), George first became interested in birdwatching when he was 12 years old. Soon after finishing a bachelor of science degree in biology at Cornell University in 1973, he began his doctoral research at the University of Colorado, Boulder, arriving in Panama in 1977 to study the ecology of hummingbirds on Barro Colorado Island. By the time he finished his doctoral dissertation in 1980, he was hooked.

He was proud to have been a founding father of the “Tropical Derelicts Award” given at the Smithsonian’s Barro Colorado Island research station to the student who spends the most time in the field each year. Recipients of the award received a box with a disintegrating tee-shirt signed by past awardees and a candle burned at both ends, among other treasures. Working with fellow graduate students on BCI, George drew the illustrations for the first Spanish-language guide to trees in Soberania National Park: Guía de los Árboles Comunes del Parque Nacional Soberanía, Panamá.

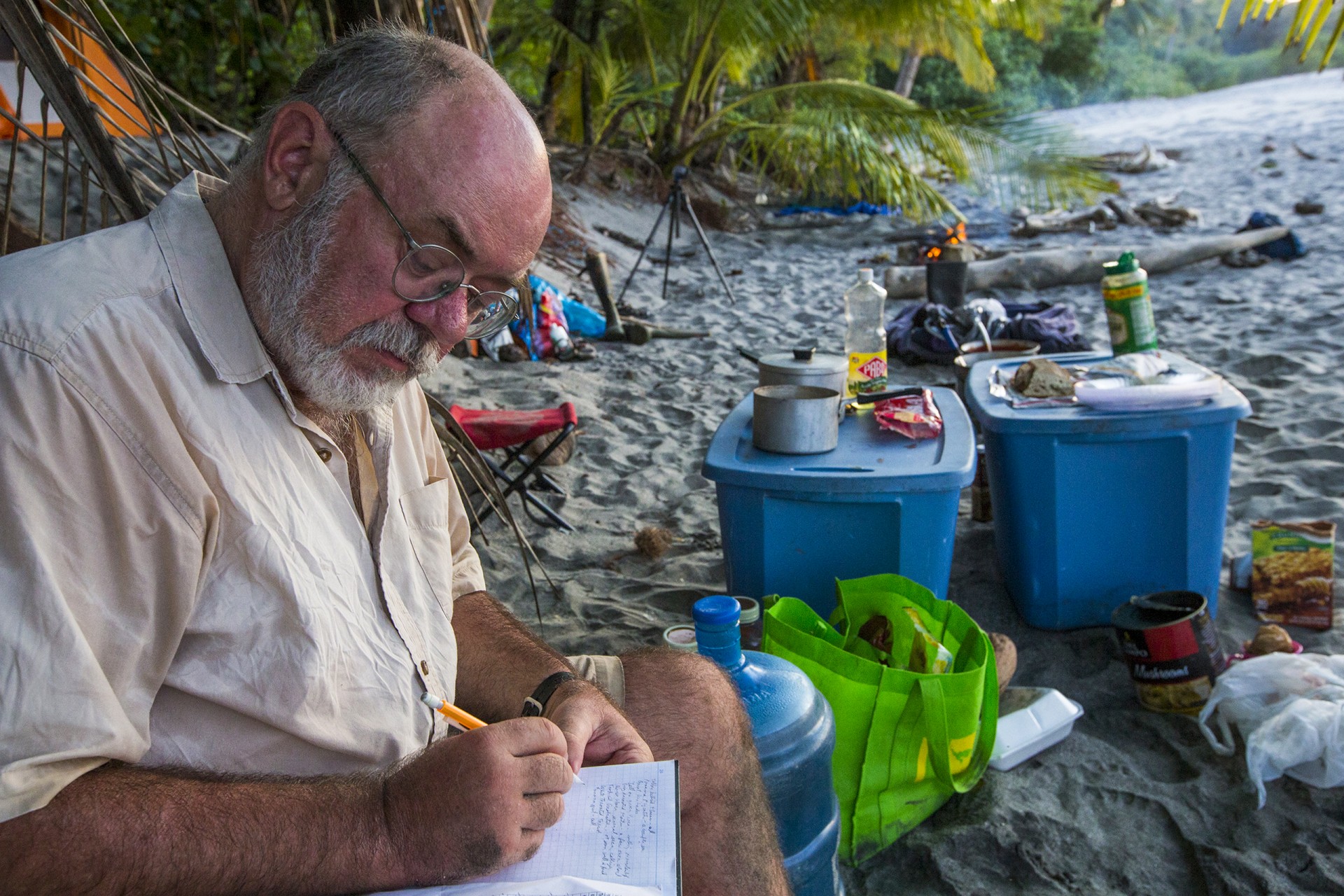

One of the important skills of a field biologist is to be able to take detailed notes under any circumstances. Here, George is hard at work on the beach on Jicarón island during the 2015 Bioblitz in Panama’s Coiba National Park and UNESCO World Heritage Site. Photo by C. Ziegler.

His subsequent project to develop the international traveling exhibit “Parting the Green Curtain,” which told the history of tropical exploration in Panama, became a great tool of international diplomacy for STRI as it traveled to Washington, DC and later to other places in the tropics, helping STRI to open doors to relationships with new institutional partners. The text of the exhibit was also published in booklet form in 1989.

For a brief time, George directed the Center for Tropical Forest Science, which since has become the Smithsonian’s ForestGEO network of 73 long-term forest monitoring sites in 28 countries.

Panama’s BioMuseo is a monument to Panama’s abundant biodiversity: George Angehr curated exhibits at the museum about the geology, paleontology, archaeology, anthropology and biological wealth of this Isthmus that connects two continents. Photo by: Brian Gratwicke.

Often “Ask George” was followed by “Where is George?” Increasingly he became involved in surveys of birds both in unexplored areas of Panama and beyond. George traveled to the Serranía de Jungurudó and the foothills around Cerro Piña and the Serranía de Majé, two isolated massifs in poorly explored Eastern Panama. Eleven restricted-range birds are only found in the Darien Highlands. With international teams of biologists, he walked streams and trails, mist netted birds, and recorded vocalizations. Specimens were sent to the Museo de Vertebrados at the Univesity of Panama and the American Museum of Natural History in New York. In the 1990’s he participated in a biodiversity assessment of birds in Peru’s Lower Urubamba river region as part of a Smithsonian Institution project.

As the handover of the Panama Canal from the U.S. to Panama drew near, George worked on several projects to provide a baseline of the natural conditions in the Canal Zone before the turnover.

This resulted in contributions to La Cuenca del Canal: Deforestation, Urbanization y Contaminación, edited by Stanley Heckadon-Moreno and Roberto Ibañez in 1999 and additional publications in Bioscience and Environmental Monitoring and Assessment.

George installing part of the exhibit at the BioMuseo representing the Great Biotic Interchange which occurred when the Isthmus of Panama rose from the sea to connect North and South America. Photo: Courtesy of George Angehr.

After the celebration of the canal turnover on December 31, 1999, George continued to organize and participate in studies that provided the scientific justification for the establishment and conservation of protected areas. For example, he contributed substantially to conceptualizing the network of “heritage trails” that formed the framework for Panama’s “Tourism, Conservation, Research” plan. In 2001 he published a study with STRI and CEASPA: the Significance of the San Lorenzo Protected area to the Integrity of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor.

When fellow researchers on Barro Colorado Island, Tom Kursar and Lissy Coley from the University of Utah were married in 1987, George gifted them this painting of a male Broad-billed Mot-mot giving a pre-nuptual moth to his mate, called “BCI Courtship.” Courtesy: Phyllis Coley.

Beginning in 2000, George worked with a creative team from architect Frank Gehry’s office, Bruce Mau Design, and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute to develop exhibits featuring Panama's biodiversity, geology, paleontology, archaeology and anthropology for the BioMuseo, a Smithsonian Affiliate museum. The museum represents an iconic tribute to Panama’s biodiversity, now hosting thousands of local residents and international tourists each year.

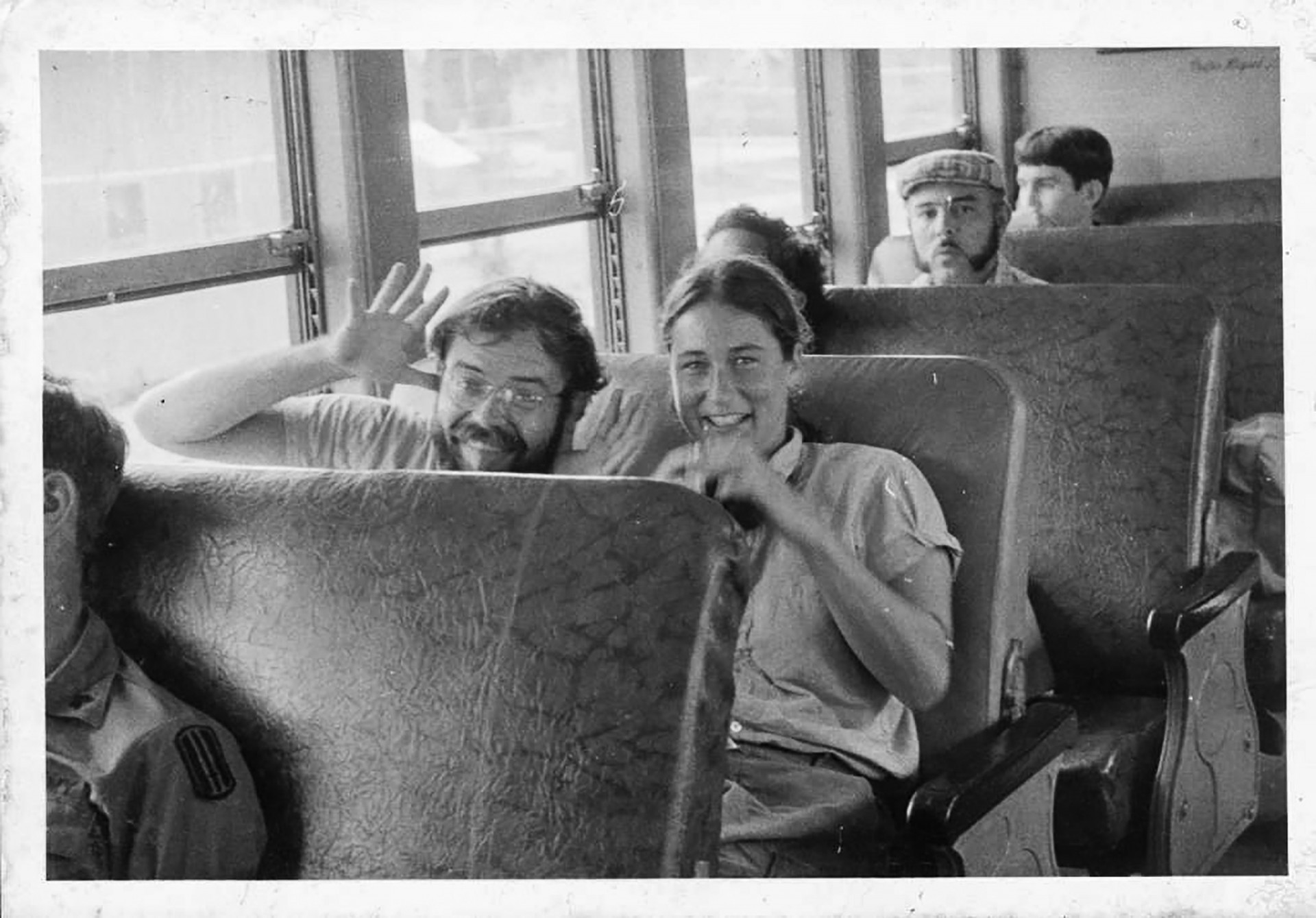

George Angehr and Lissy Coley. Photo: Courtesy of George Angehr.

He also wrote text for exhibits at Panama’s museum of anthropology.

For a country of its size, Panama’s bird diversity is extraordinary. The tips of North and South America meet here, migratory birds use Panama as a bridge and Panama is home to its own set of endemic birds found nowhere else on Earth.

Not only did George become a regular organizer and participant in October counts of the rivers of migratory hawks and vultures that pass over the isthmus, with Dodge and Lorna Engelman, George first wrote Where to Find Birds in Panama, a Site Guide For Birders, published in 2006 by the Panama Audubon Society. This was followed in 2008 by A Bird-Finding Guide to Panama. At the time, the only complete field guide for ornithologists was A Guide to the Birds of Panama by Robert Ridgely and John A. Gwynne, first published in 1976. Ridgely’s guide was packed with information from Smithsonian explorer Alexander Wetmore’s three volume set, The Birds of the Republic of Panama, and detailed notes provided by Panamanian ornithologist, Eugene Eisenmann, among other sources.

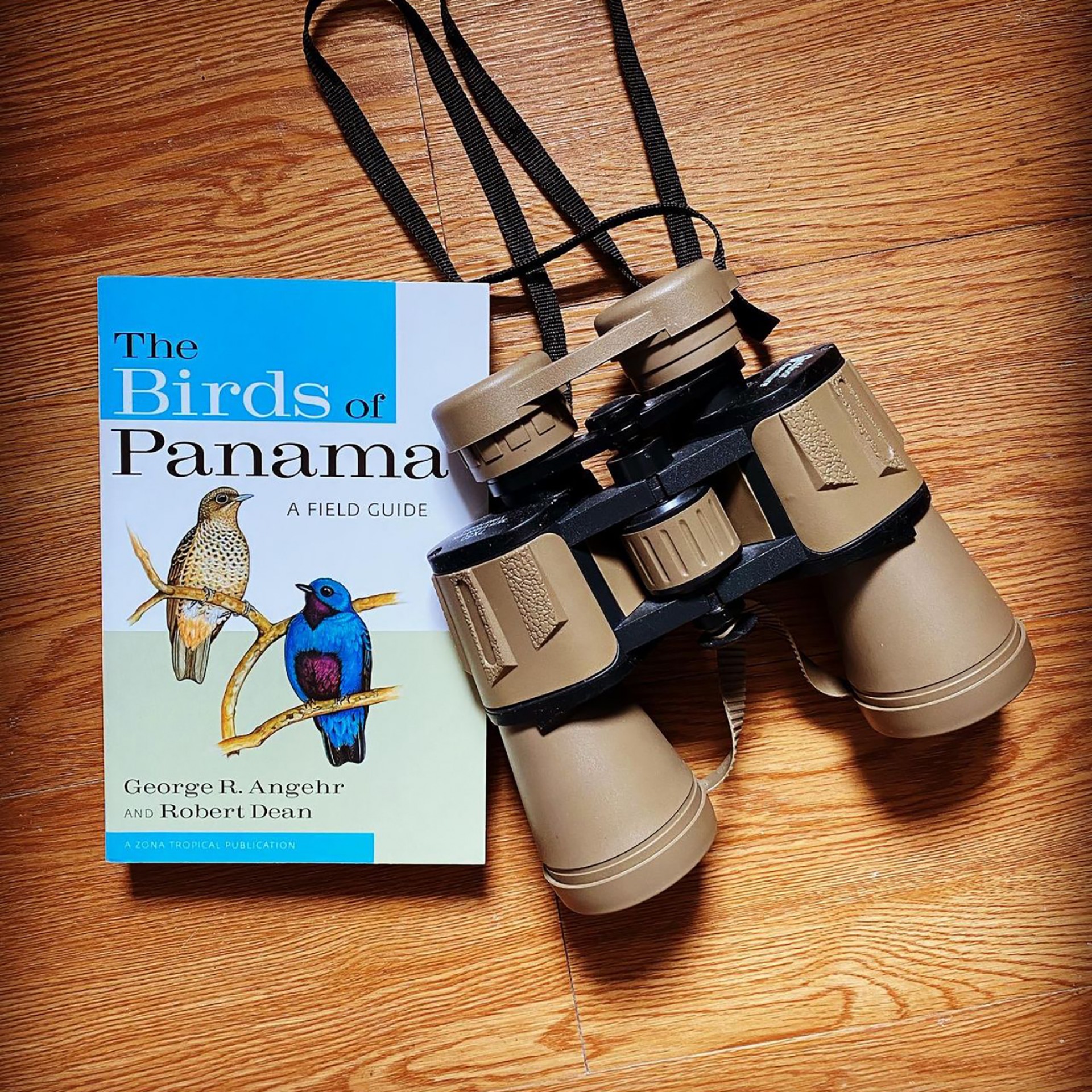

George realized the need for a more portable guide tailored to the needs of field biologists and tour guides. With Robert Dean, he created The Birds of Panama: A Field Guide in 2010. In the new guide, species descriptions and range maps were presented on pages facing the illustrations of the birds, making it much easier to quickly identify birds in the field. Recently, he helped to create a bird guide for use by local tour guides in Panama’s indigenous comarca, Guna Yala.

He continued to be invited as the team ornithologist on expeditions, now in Africa and New Zealand as well as in the Americas. In 2008, George and colleagues reported a new species of African forest robin from Gabon.

By creating a compact guide book to the birds of Panama, George made it easier for students, researchers and tourists to correctly identify birds to species. Photo by: Sonia Tejada.

George was a key, go-to person for STRI’s Advancement office because he was always willing to guide VIP visitors. Not only could he identify the birds, he also filled dull moments with amazing natural history stories and amusing tales of folly. These are some of the same qualities that distinguished George as a good colleague and friend: easygoing and quick to grin, soft-spoken and humble. He often invited people who were new to Panama and students new to the tropics to go birdwatching.

In 2013 Partners in Flight, an international bird conservation group, presented George with its first Lifetime Achievement Award. The award recognizes individuals who contribute significantly to management, conservation and habitat restoration for land birds. conservation and monitoring of birdlife in the former U.S. Canal Zone.

With the Panama Audubon Society, George successfully elaborated the Important Bird Area Program and Key Biodiversity Areas directory for Panama as part of BirdLife International’s efforts to identify all of the sites that need to be conserved in order to protect all bird species in the world.

George demonstrating the correct method to pick up a sloth. Photo: Courtesy of George Angehr.

Beginning in 2015, George offered his skills to the development of the Coffee Exploration Center in Boquete, Panama, which opened in 2017. More recently he was working on a new Visitors’ Center in El Valle. According to Mercedes Morris, his collaborator on those projects, and also his birding friends from the Audubon Society, he was hit very hard by the strict lockdown imposed during the pandemic, which confined him in his apartment in Panama City.

Today, a Google search provides a quick answer to “How many bird species are there in Panama?” on iNaturalist: 1002. George knew this, but he knew much more and could integrate and synthesize information brilliantly, and present it in ways the public could understand: which were the most recent discoveries and who made them, which species were only found here and which were the most threatened. His expertise and generous nature will be sorely missed, especially at this moment in history when not only the future of birds, but the integrity of the entire natural world is at stake.