Disappearing Frogs

It isn’t easy being captive

Panama

To save frogs from an extinction-causing fungus, Smithsonian scientists needed to innovate captive feeding and breeding techniques.

To collect frogs, Smithsonian scientist Roberto Ibáñez has hiked deep into forests and has braved venomous snakes, wild boars, jaguars and steep, slippery creeks in the remotest and wettest parts of Panama. Many times he’s repeated long treks to assure he has enough frogs to save species from extinction.

And that was the easy part. Ibáñez and colleagues have had to mobilize every resource at their disposal to establish captive breeding programs for frogs susceptible to the chytrid fungus that has wiped out some 200 amphibian species worldwide. “It’s a complicated process”, Ibáñez says, especially for Atelopus species like Panama’s golden frog.

1) Collect

Assurance populations need 20 males and 20 females able to reproduce. Females are generally harder to find than males. When the disease gets to a population before scientists do, obtaining enough healthy individuals is a huge challenge.

2) Quarantine

Before joining the Panama Amphibian Conservation and Rescue (PARC) project’s breeding program, frogs need a 30-day quarantine. This includes a preventive treatment for the fungus, and endoparasites. Usually most frogs survive, but some species are less resistant than others.

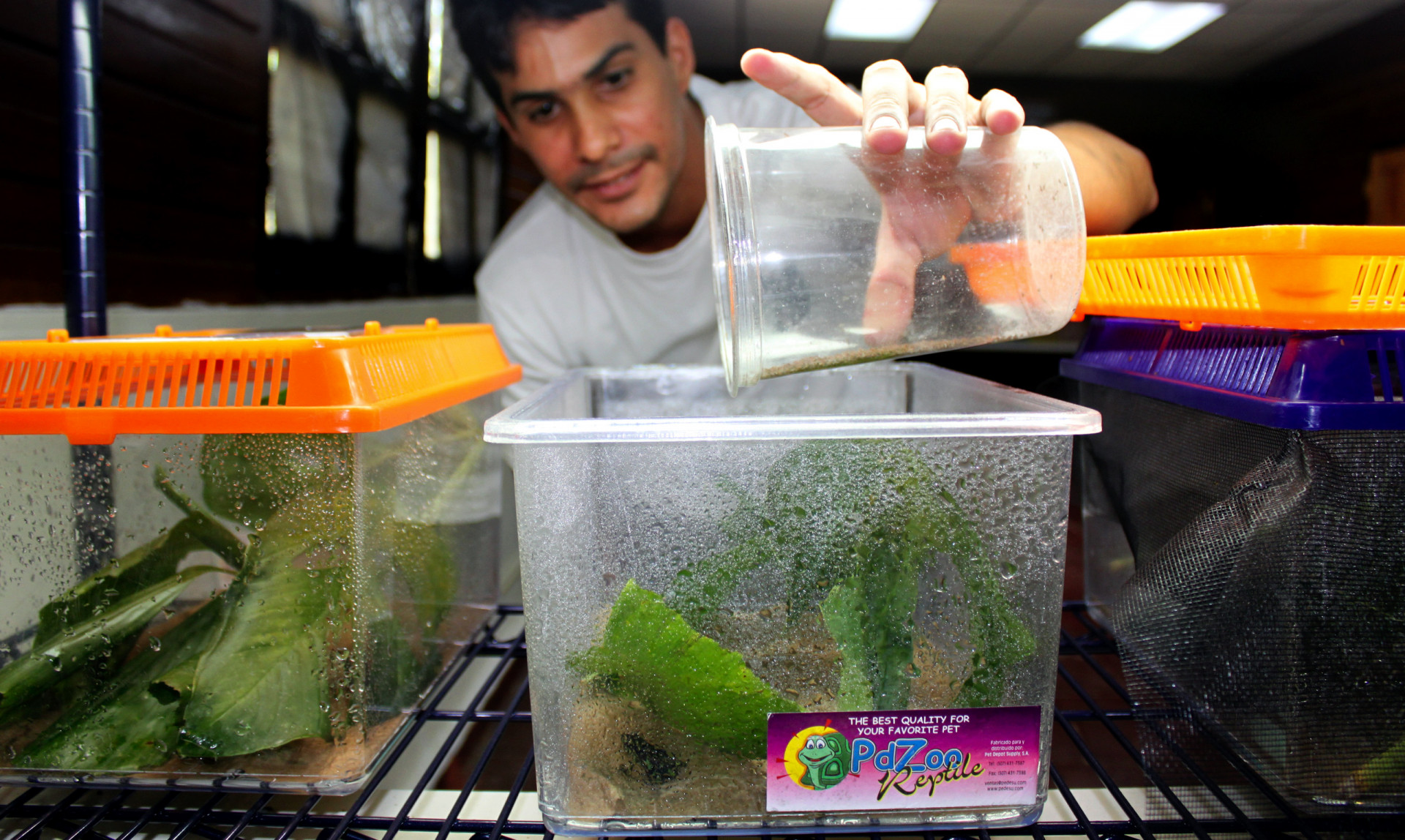

3) Feed

Good frog breeders must be good insect breeders, since there are no insect farms in the country. Rearing fruit flies and crickets sounds easy but the bugs must eat an enriched diet and be peppered with vitamins and calcium before being fed to the frogs.

4) Breed

A tank with plants, rocks and water resembling native habitat (at perfect ambient temperature) sets the mood. Even then, frogs can go for days without laying eggs. This can emaciate the male, who doesn’t eat during the courtship process. A female can go a month without laying eggs and even then, clutches may not hatch. But results are improving.

5) Raise young

Tadpoles have a different diet than their parents — they’re fed a paste of algae and fish food that’s spread and dried on a Plexiglas plate that is placed in the water. Once they metamorphose into juveniles, they eat tiny critters called collembola, or springtails.

6) Maintenance

The retrofitted shipping containers where the frogs are housed provide vital life support. Two air conditioning units are used in each container to provide back-up in case the primary unit fails. Hygiene and abundant purified water are also essential to frog survival.

7) Reintroduction

The current goal is to maintain a first generation of 30 males and 30 females per species bred in captivity. The project will be able to conserve up to 90 percent of the frogs’ genetic diversity over 100 generations, allowing ample time to develop reintroduction strategies. When reintroduction time arrives, PARC will require to breed hundreds of individuals to be released in the wild. “We haven’t gotten there yet,” said Ibáñez. “But we’re close.”