Hidden Marine Species

Buckets of biodiversity

Las Perlas Archipielago, Panama

Aboard a research vessel in the Gulf of Panama, a Smithsonian research fellow explores the hidden biodiversity of the tropical ocean.

The seawater Michael Boyle collects aboard a research vessel in the Bay of Panama fails to impress at first glance. "Initially, it just looks like a bucket of dirty water," said Boyle, as he retrieves a red, white and blue plankton net, which resembles an airport windsock with small cylindrical filter at the end.

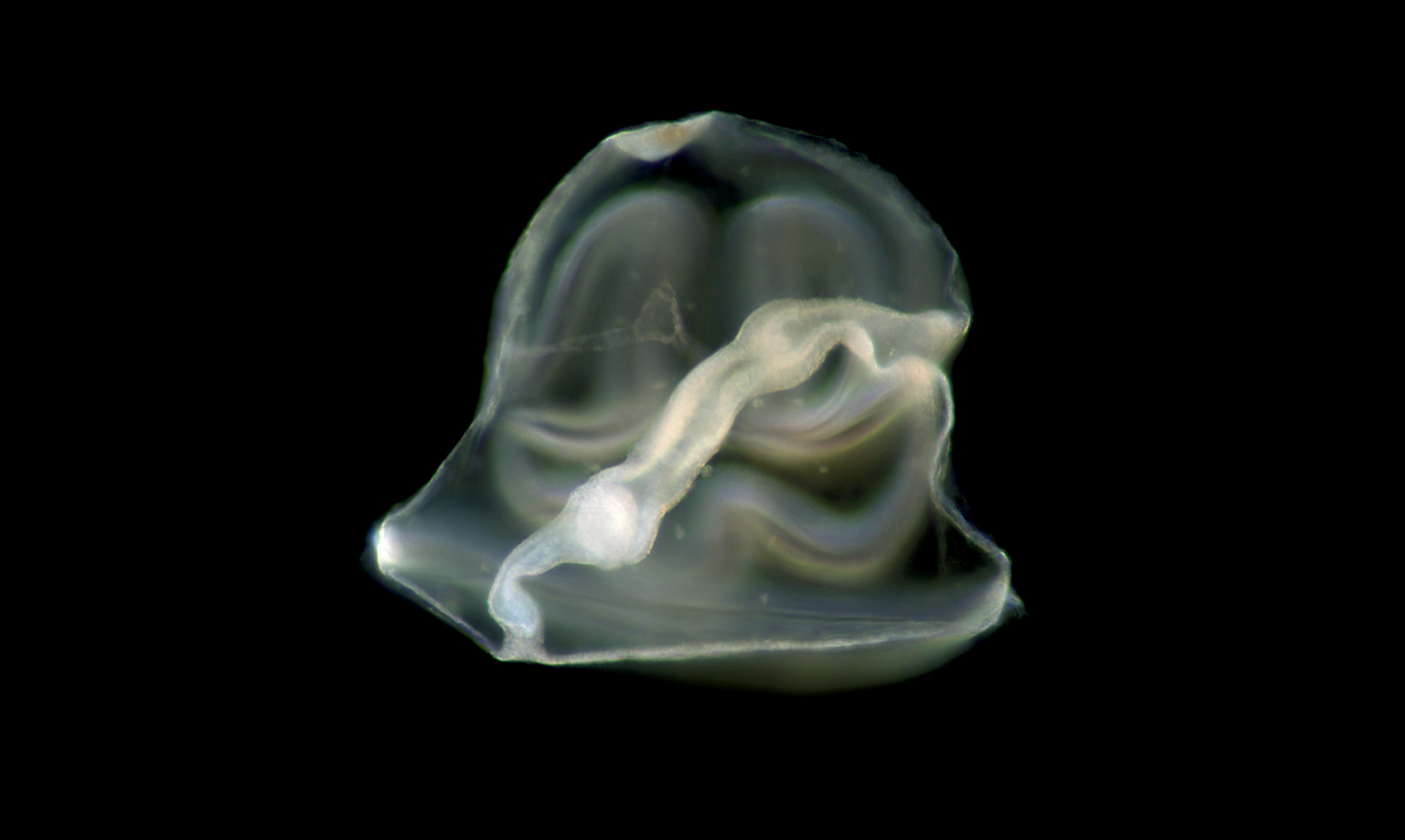

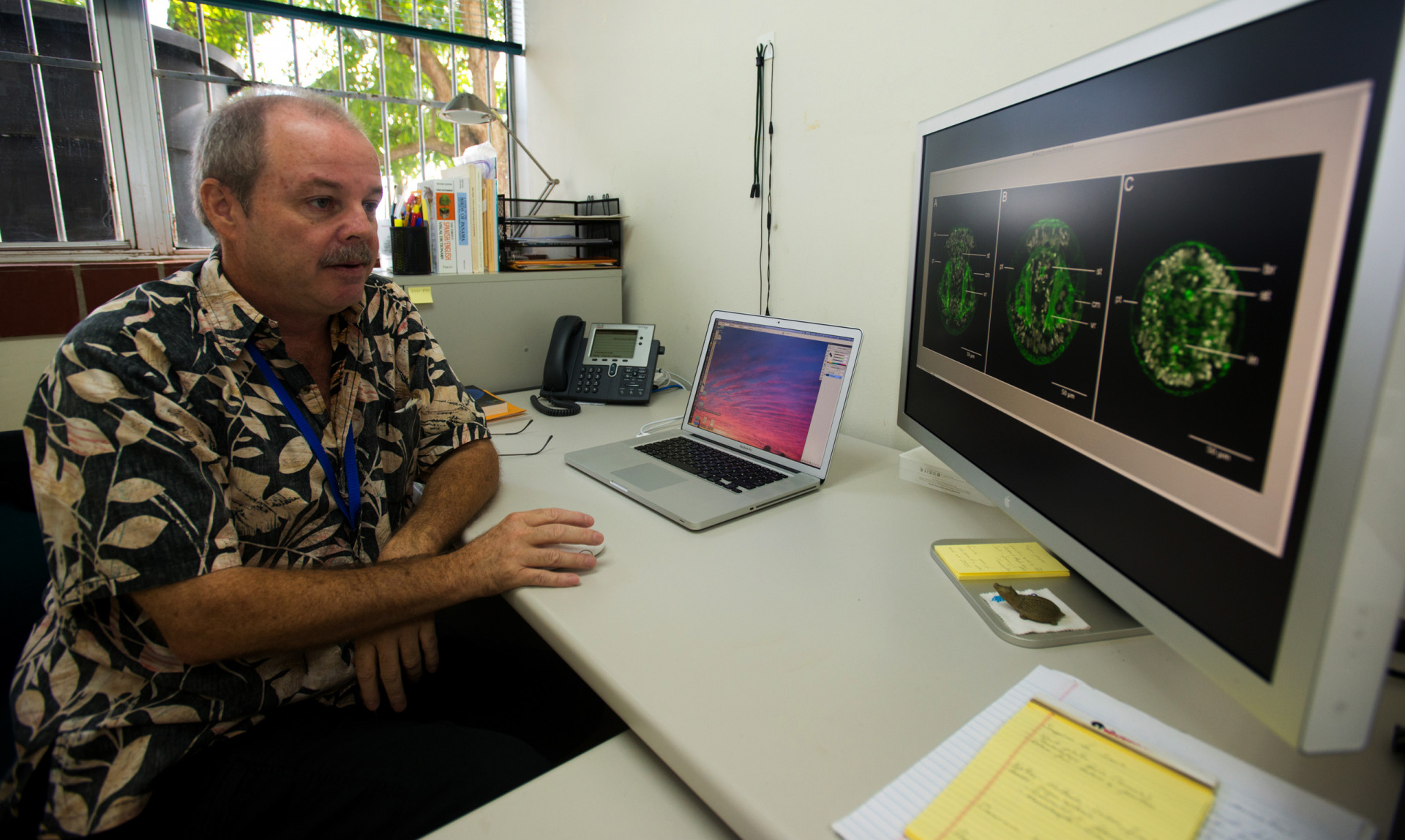

Each bucket holds some 10,000 organisms and Boyle will examine and image many of them under a microscope at STRI's Naos Island Laboratory. Larval forms of little-known sea creatures in coastal waters may help clear up mysteries surrounding the development and dispersal of even well-known species.

"Eventually, some of these larvae will metamorphose into what we recognize along the beach — sea urchins, snails or crabs," said Boyle, a developmental biologist whose fellowship has been supported by the 1923 Fund as part of a collaborative partnership between STRI and the University of Florida’s Seahorse Key and Whitney Marine Labs. "Before that happens, they exhibit microscopic life history stages in every color and form you can imagine."

Underscoring just how little is known about the larval stages of common marine invertebrates — what they look like, how they swim and where they go — Boyle will need to match DNA from adult species to identify many of them.

"It's important to get baseline information for future investigators," he said. "Currently, we don't really know the biodiversity of larval forms that are here."

Boyle specializes in the development of Sipuncula, including their unique pelagosphera larvae. These unsegmented marine worms haven't changed much in about 520 million years and, as basal members of the segmented annelids, they hold important clues about the evolution of animal body plans.