Did you know that vampire bats often make long-lasting friendships?

Trópicos

Resilience

On March 25th 2020 a strict quarantine was implemented in Panama as part of the country’s efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19. Since then, most of the scientists and staff at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) have been working from home. A few others found creative ways to continue performing essential tasks. We had to change, we had to adapt. We remained hopeful. In this digital issue, we will tell you the story of how we continued to do and support science in spite of the pandemic.

The importance of science

during crisis

always.

Science during

times of crisis

Since the first case of COVID-19 was reported in Panama, scientists from different institutions in the country joined forces to find fast and efficient solutions to control its spread. Watch them explain the importance of science, especially during times of crisis.

Our planet's plight

We haven’t lost hope. In the words of our acting director, Dr. Oris I. Sanjur, “We have to find solutions” to the major challenges that our planet is facing. One of these pressing challenges is the accelerated deterioration of our natural ecosystems and its imminent threat to all forms of life on Earth. Its most recent repercussion on humans has been the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. To find solutions, in the words of teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg, we must “unite behind the science.”

Undeniable

We don’t know what we’ve lost, unless we’ve monitored it. This is why STRI has been collecting environmental data in Panama since 1972. What can these patterns teach us about the past and future of the country’s climate?

Unique mammals

Bats are often misunderstood and held accountable for the spread of diseases from animals to humans. Most recently, they have been blamed for causing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet human actions, such as the destruction of ecosystems and the illegal wildlife trade, are the main reason why pathogens found in wild animals are suddenly infecting humans.

In fact, bats are incredible creatures that fulfill an essential role in nature.

Bats

There are

more than

1400

species worldwide

In Panama

there are about

120

species of bats

Their diet consists of

fruit, nectar,

insects, fish, frogs,

lizards, birds, blood

and even other

species of bats

They can live up to

40

years

Bats are necessary for nature

and the environment

They aid with

Seed Disspersal

They are important

Pollinators

They help with

Insect Control

saving agribusiness millions

Smithsonian BatLab researchers in Panama have discovered that bats and humans share many common traits. For example:

They also care for their sick family members by grooming and feeding them.

And just like new parents do, some bats employ baby talk when communicating with their pups, a behavior that may help with language development.

We hope these stories help spread our fascination for these wonderful mammals.

Locked up

Shortly before the STRI closed its doors due to the arrival of COVID-19 in Panama, STRI fellow Edwin García locked himself up in the lab for several days, to finish processing all the data for his research project on the value of native trees for reforestation.

Cosmopolitan

Dumas Galvez, who was recently awarded a prestigious scholarship from the Smithsonian in Washington for his research on ant immune systems, had to transport 70 ant colonies to his home in order to continue studying them during the quarantine.

Quarantine champions

Although most of the Smithsonian staff and scientists have been working from home since March, not all essential duties can be completed remotely. Meet some of the superheroes who have left the safety of their homes to protect our animals, forests and laboratories, and ensure administrative support.

Pandemic challenge

Two local marine biologists radically changed their work rhythm when the coronavirus pandemic hit Panama. They went from collecting marine data for research projects all around the Bocas del Toro archipelago, to keeping an entire research station afloat on their own.

Superheroes

Despite the coronavirus outbreak in Panama, the park rangers at the Barro Colorado Nature Monument can’t stay at home. They have continued to monitor the protected area all day, every day, on the lookout for threats to the forest and its animals.

Quarantine

The animals at the Punta Culebra Nature Center miss receiving the daily influx of curious visitors, young and old, eager to learn more about them. While they wait for us to return, two silent heroes have continued to take care of all their needs.

Where do they come from?

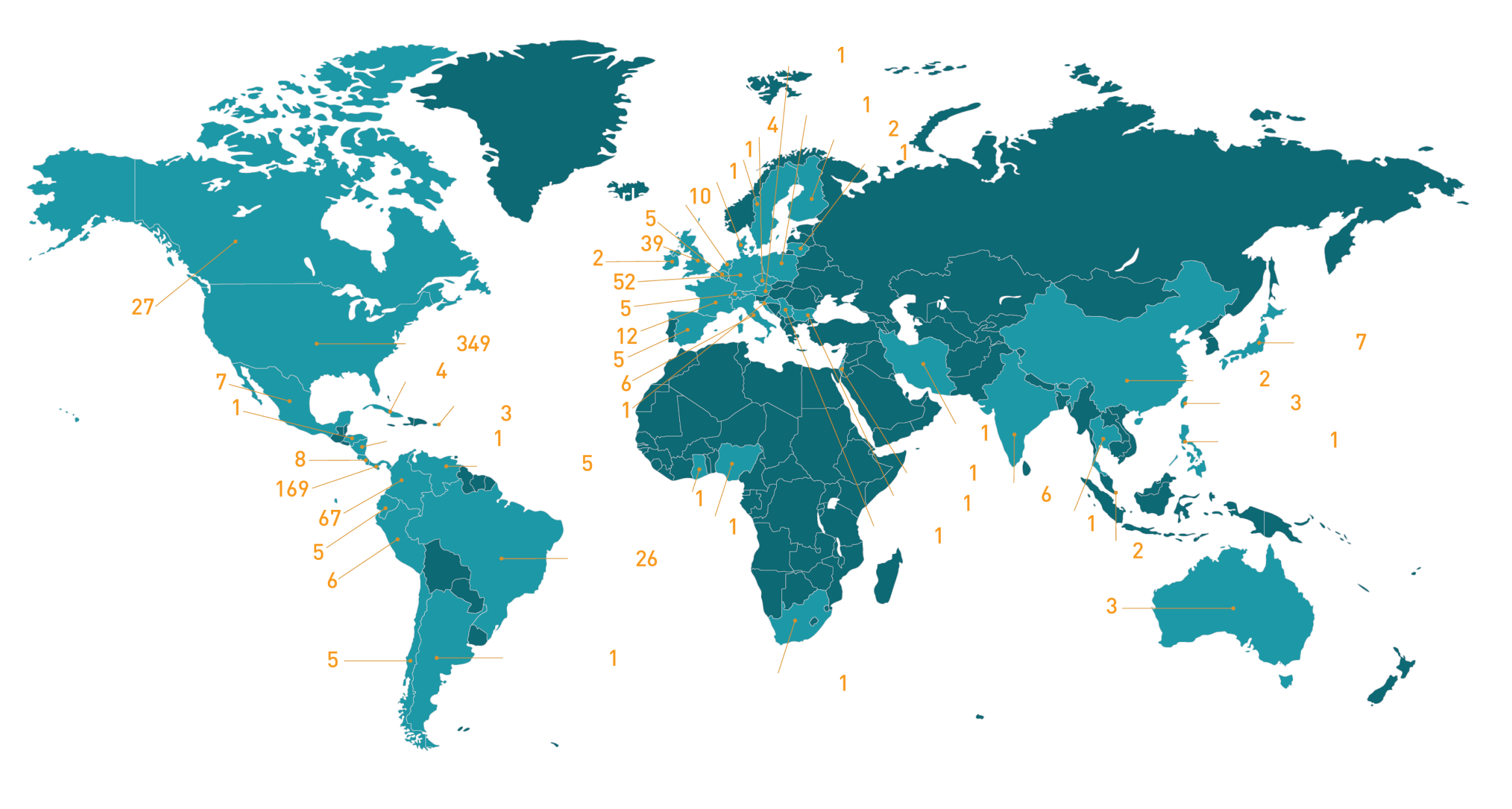

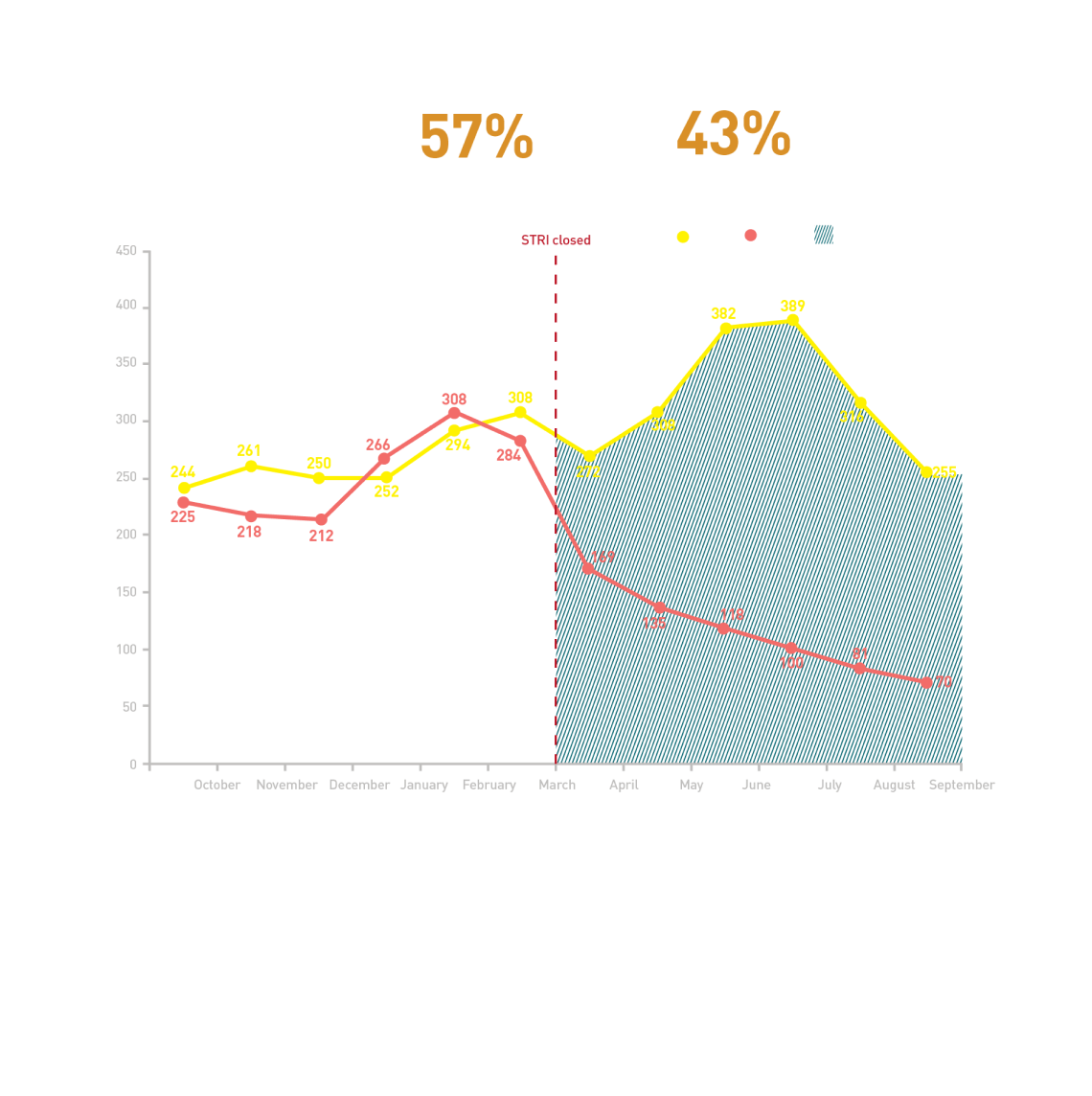

Every year, STRI hosts hundreds of fellows and interns from all over the world. Half of them come from Latin America and the Caribbean.

Main regions

2019 vs 2020

In 2020, the pandemic interrupted 226 postdoctoral fellowships, 300 predoctoral fellowships and 321 internships.

Zarluis Mijango Ramos

Botany, Plant ecology

The pandemic surprised Panamanian botanist Zarluis Mijango Ramos while he was collecting data in the Fortuna hydrological reserve as part of his master's thesis in plant biology at the University of Illinois. With the shutdown of national reserves and the closing of STRI in March, he only managed to collect half of the information he needed.

"I am looking at how monodominant forests affect the diversity and abundance of the other species that occur in it."

These are forests where a single species accounts for more than 60% of the number of trees. To fill this gap, he is using additional data from another scientist.

And while he's aching to be around plants again, Zarluis is applying to doctoral programs and hoping to eventually return to Panama, to continue doing research in tropical forests.

Photo credit: Keri Alexandra Greig.Charlotte Steeves

Biology

When the pandemic started, Charlotte was in the middle of gathering data in Boná island about seabird exposure to organic contaminants in their diets. She first became fascinated by the diversity of tropical birds in 2018, as a STRI intern. This led her to return as a master’s student in the STRI-MCGill Neotropical Environment program, to collect data on the island and analyze it alongside chemists from the Technological University of Panama.

"I really love those birds, and one of the biggest threats they face is contaminant exposure."

However, she had to take off in one of the last flights out of Panama when the pandemic started. She also had to adapt her thesis, when she realized that returning to Bona island was not possible in the short-term. She continues to explore connections around exposure to contaminants in seabirds, but with data from other parts of the world.

Photo credit: Charlotte SteevesClaire Williams

Microbial ecology

Claire planned to spend her summer in Panama, studying the effects of climate change on lizard gut bacteria. As a biochemistry student, she had learned about how gut microbes can modulate emotions, metabolism and the immune system, and began wondering about how they would interact with environmental change.

“If the microbiome changes it can affect host fitness and survival, and because lizards can’t regulate their own body temperature it’s particularly important.”

She had invested the previous summer in Panama, as the microbiologist on a lizard-climate change project led by Tupper fellow Michael Logan. But 2019 was a very dry year, and the lizard microbiome results looked unusual. In 2020, Claire expected to gather more samples and compare them to 2019. However, she never made it to Panama. Her funding was put on hold for a year, so she hopes to return in 2021.

Photo credit: David Curlis

Betzi Pérez

Behavior and acoustics of marine mammals

Betzi planned to spend the last year of her doctorate at McGill in Montreal, writing her thesis on the impact of tourism and boat traffic on the bottlenose dolphins of the Bocas del Toro archipelago in Panama. She also had an upcoming internship in Alaska, where she would analyze the stress hormones levels in some dolphin samples. With the pandemic, however, she was unable to travel to Montreal or send her samples to Alaska.

Without these analyses, comparing the stress levels among dolphins that are exposed to heavy boat traffic with those that aren’t, she’ll have to adapt her dissertation. Her plan B would be to return to Bocas del Toro to obtain additional information regarding the effect of boat noise on dolphin behavior. Here is the silver lining:

"The quarantine has given us a unique opportunity to record with a reduced number of boats circulating in the archipelago."

Photo credit: Chelina Batista

Estefany Caroline Guevara

Animal physiology and behavior, thermal ecology

Estefany Caroline had spent two summers in Panama studying Neotropical frogs. She was curious about their temperature tolerance, particularly in embryos.

"I wanted to know if the frog embryos could escape from their eggs when heated. Being able to determine the temperature limits that can lead species to change their behavior under climate change scenarios is very important."

A preliminary experiment in the lab showed that they could escape. In 2020, as a first-year doctoral student, she expected to repeat the experiment under natural conditions. However, the pandemic changed her plans and she spent those months writing a chapter for her thesis. She hopes to return to Panama next year.

"During this time, we all had to stop for a bit to recap. I had completely different plans for this year, but sometimes we have to flow with what comes up along the way."

Photo credit: Karen Warkentin

Benjamin Rubinoff

Marine community ecology

Benjamin’s research in Panama has been disrupted by extraordinary circumstances for two consecutive years. Last year, the United States government shutdown prevented him from travelling. This year, it was cut short because of the pandemic.

He wants to understand how predators affect marine invertebrate communities across the reef, mangrove and seagrass habitats in the Panamanian Caribbean, and whether this effect varies among younger and older communities.

He had to leave Panama before he was able to observe any predation, but he gathered some useful data.

"I was able to start making a species list of the organisms I found at the site. It will help inform me the next time that I try this."

Benjamin has some funding to return in January, when he would have to re-start the experiment. If he can’t return, he would have to find a plan B for the last chapter of his dissertation.

Photo credit: Carmen Schloeder

Monica Carvalho

Paleobotany

Monica was in the last stretch of her three-year Tupper postdoctoral fellowship at STRI when the pandemic started. As a paleobotanist, she explores how climate change affected tropical forests during a global warming event 56 million years ago.

Her most recent experiment involved subjecting plants to the high temperature and carbon dioxide levels from that period, using plant families that have existed in the tropics since then.

Right before STRI closed its doors, she collected her samples quickly and froze them for later. She is home in Colombia now, hoping to return to the laboratory soon. In her analyses, she’ll explore whether there are any observable anatomical changes between the current and ancient environmental conditions, and if they can be detected in fossils.

"I intend to continue studying ancient living plants in parallel with fossils, because there is no way to understand the fossil if we do not understand the living."

Photo credit: Sebastián Gómez

What we look forward to

After being confined for seven months and patiently adapting to a new reality that required us to learn new technologies, interact with our colleagues through a screen and stay away from our laboratories and the field, some of us reflect on what we look forward to after the pandemic.

Steve Paton

I am looking forward to renewing the many Physical Monitoring Program climate and oceanographic monitoring activities that have been suspended since the beginning of the pandemic. Everyone in my program would much rather be back at work collecting the data that supports the research for so many scientists. I am particularly looking forward to continuing the expansion of our marine monitoring activities, in terms of the number of variables and the locations.

David Kline

I am most looking forward to resuming my field work in the Tropical Eastern Pacific and in the Caribbean. In the Pacific, it will involve monitoring critical environmental conditions (temperature, pH, oxygen and light) near where the corals are living. We will also monitor the growth of our corals and the competition with other reef invertebrates and macroalgae, and investigate changes in their microbiome and genomics in response to environmental stress.

Francis Torres

This pandemic has left us many lessons. Socially and work-related, we have learned to use new tools to communicate and continue with some of our duties. My hope is that this experience will help us improve our services and increase the use of virtual technology where we interact with the public, as well as implement virtual and interactive tours that allow us to connect with the population that has restricted or limited movement capacity.

Rachel Collin

Bocas Station Director

I look forward to seeing the ocean again, to getting our oceanographic instruments safely out of the water, and to unpacking the new equipment that has arrived to document plankton diversity and abundance in the Bay of Panama and Bocas del Toro. I also look forward to congratulating two of my University of Panama students on defending their undergraduate theses and graduating (this was planned for March or April).

Juan Perez

I would like for all of us to return and share our day to day like we did before: a coffee, a conversation, some advice. Above all, I would like to continue learning and promoting the knowledge that our work environment provides and regain that connection with nature. I look forward to taking photos of plants and animals again and being able to share them with my friends and colleagues.

Elizabeth Sánchez

STRI Library

When I return to the STRI library, I look forward to finding the collection and the building clean. Also my day-to-day life at the library, the coexistence with my co-workers and the attention I give to users who are looking for information to develop their research. I miss being in contact with books and magazines that are a source of inspiration and professional development.

Félix Rodríguez

Returning to my office generates a mix of feelings: sadness, happiness, and also a lot of hope. Sadness, as this time at home helped me value spending time together as a family. Happiness to see my friends and work colleagues again. Without a doubt, my greatest hope is that we can work together as a great family, and that together we can overcome this crisis. One Smithsonian!

Sabrina Amador

Back at STRI, I look forward to helping rebuild our academic community, and supporting our students and partners. I look forward to getting back to work in the field and increasing our knowledge of the behavior and ecology of Neotropical animals.

Leila Nilipour

Office of Communication

In returning to STRI, what I look forward to the most is joining scientists in the field and in their labs to learn about their research questions right where the action happens, whether it be snorkeling in between the mangroves, exploring remains in the middle of an archaeological excavation or hiking deep into a humid tropical forest.

Science in

the time of Covid

Matthew C. Larsen, STRI Director Emeritus

As NYT columnist Tom Friedman has written, mother nature governs us all; her laws are those of biology, chemistry and physics, and they must be obeyed. The Covid virus appeared because we have upended the balance with mother nature. Paraphrasing the title of the novel by Gabriel García Márquez, “Love in the Time of Cholera” (El amor en los tiempos del cólera), as we live through this time of Covid, science must go on, even under these most difficult circumstances.

Our upended world has become ‘Macondo’, the place in which the surreal replaces our ordinary routine: societal behaviors have shifted, our ability to conduct day-to-day affairs is highly restricted, and many have grown numb to the grim news reported in newspapers and on television. In spite of the trials we face in navigating life in the time of Covid, our STRI science mission continues to advance. The pandemic limits our mobility and social interactions but it presents us with the requirement that we collaborate across scientific disciplines in our family of scientific institutions to demonstrate the value of science to our society and our economy.

We have an obligation, as scientists and scientific institutions, to inform the public with factually-based information about what we know and what we don’t yet know. Science communication is more relevant now than ever in this time of Covid.

The Covid pandemic has challenged us as much as anything that most of us have encountered in our lifetime. Fortunately, we are finding ways to respond and continue our scientific mission, as the stories in this special issue of Tropicos describe. A particularly important task for example, is to carry on with our environmental monitoring program, in which we collect basic data such as air temperature, rainfall, wind speed, streamflow, sea level, and salinity in lakes. Some of these STRI data go back a century and become more valuable, as sentinel data sets, with each passing year by providing insights into the local impacts of climate change. With regard to streamflow, it has been said that “you can’t manage what you don’t measure”—these data that help us better understand hydrologic processes. Good management of water resources is vital for Panama, as anyone at the Panama Canal Authority will attest.

None of us can accurately predict the future, but our research allows us to make well-based estimates and projections of what we can expect, here, and across the world. In the end, without basic and applied research to inform government policy decisions, we are ‘flying blind’.

Connection and Hope

In connection we find hope. And hope gives us the strength to keep going. Scientists have not yet returned to the field or to their laboratories. And from home we continue to carry out the support tasks that have allowed us to sustain science throughout this pandemic.

We are united by our commitment to a single mission - to increase and spread knowledge about the tropics and the communities that live in it - and we are connected by the hope that after the pandemic we will return to a different institution, a stronger one, that is prepared to face a new normal.

Each one of us - collaborators, fellows, visitors and friends - is essential for this institution to celebrate another hundred years, united by the well-being of science, education and humanity.

Oris I. Sanjur, PhD.

Acting Director

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute

Credits

Trópicos Team

Leila Nilipour: Concept and writing

Paulette Guardia: Concept, design and illustration

Ana Endara: Filming,video editing

Jorge Alemán: Web design

Sonia Tejada: Translation

Beth King: Text editor

Lina González: Design supervision

Johann González: Web development

Communications Team

Linette Dutari: Associate Director for Communications

Beth King: Communications manager, writer and editor

Lina González: Design supervisor

Paulette Guardia: Graphic design specialist

Ana Endara: Videographer

Sonia Tejada: Media relations, translations

Jorge Alemán: Graphic design specialist

Leila Nilipour: Copywriter and journalist

Acknowledgments

TVN and Medcom: Video footage

Collaborating photographers: Image credits within articles

Adriana Bilgray and Paola Gómez: Fellows map and infographics

STRI scientists, fellows and staff